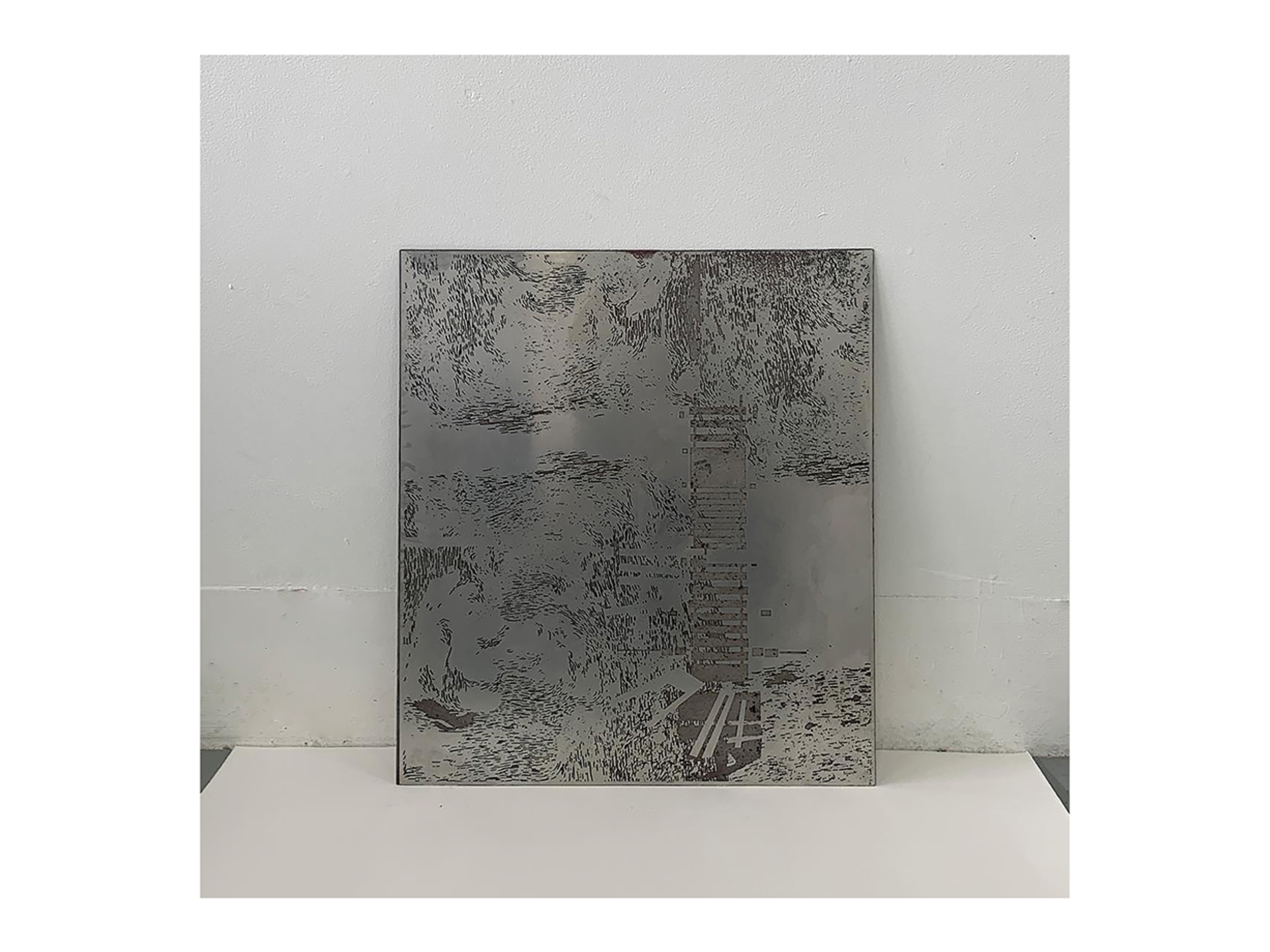

Through the makings of this thesis, the line between material and drawing is explored through a very specific type of printmaking. The surface on which we scribe embodies the same erosive conditions of the thing it's representing. Our impressions of change and observations create a wider gap through which we might draw new conclusions. The drawn collation of plates and reliefs resulting from this research formulate an indirect connection between an eroding site and the erosive process of intaglio printmaking. Continuing from the spatiality of the previous woodblock prints, this process draws forth a separation of the plate and the relief. In woodblock, the block and the relief work together as they are a direct reproduction of one another. In intaglio print, the reverse is investigated. The plate suddenly presents a secondary quality to the print taken from it. Each being residue of the other’s process.

In a pictorial sense, one can draw directly from a landscape, however, pulling a line across a page isn’t a horizon until you define it as one. When the surface on which we scribe becomes physical, unstable, and transformative, the impressions we might draw from them change alongside it. The line becomes a presence; the etch becomes an absence. They propose a new form of architectural drawing that not only parallels but indeed reveals and critiques the physical and ephemeral changes in which architecture stands against time.

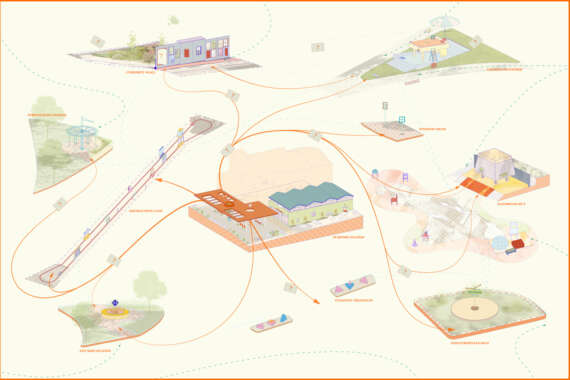

At this point of my thesis research a site is introduced at two scales; there is a personal and critical reflection on the architectural and drawn impressions we experience. The makings touch on the materiality of place and the use of erosion as a drawing technique. The first scale was the inlet of Awaroa in the Abel Tasman National Park, an ever-changing inlet of sand and channels that have shifted for thousands of years. The second scale resulted from the inlet's recent battles with the ocean, the bank bordering a row of residents in the national park.

These makings collide with the realities of erosion on Aotearoa/New Zealand’s coastlines, the monoprinting and woodblock techniques speak as methodologies themselves as acts of personal and material investigations.