Common Ground: Weaving a Conduit for Environmental Knowledge at Hiwiroa Station

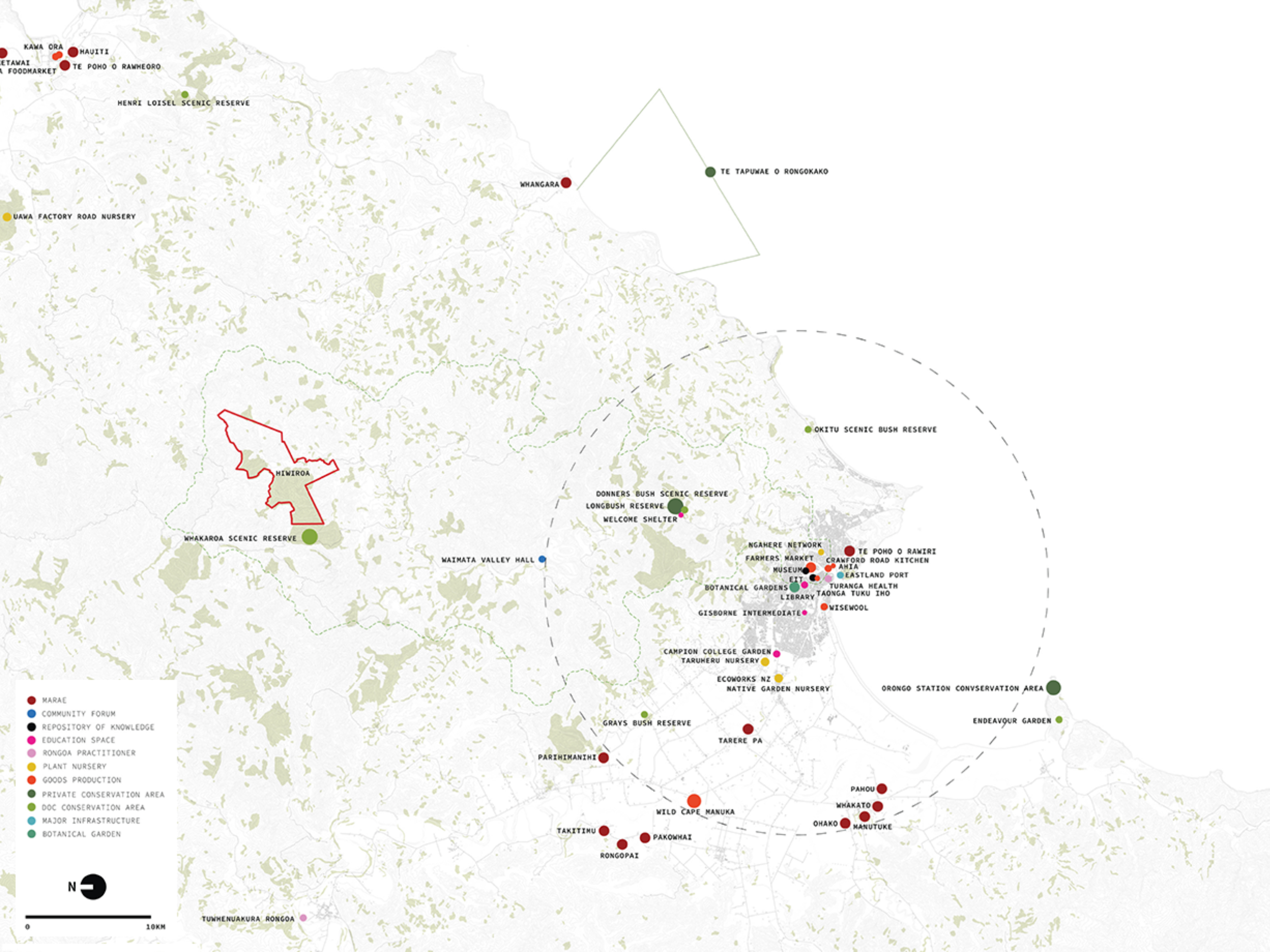

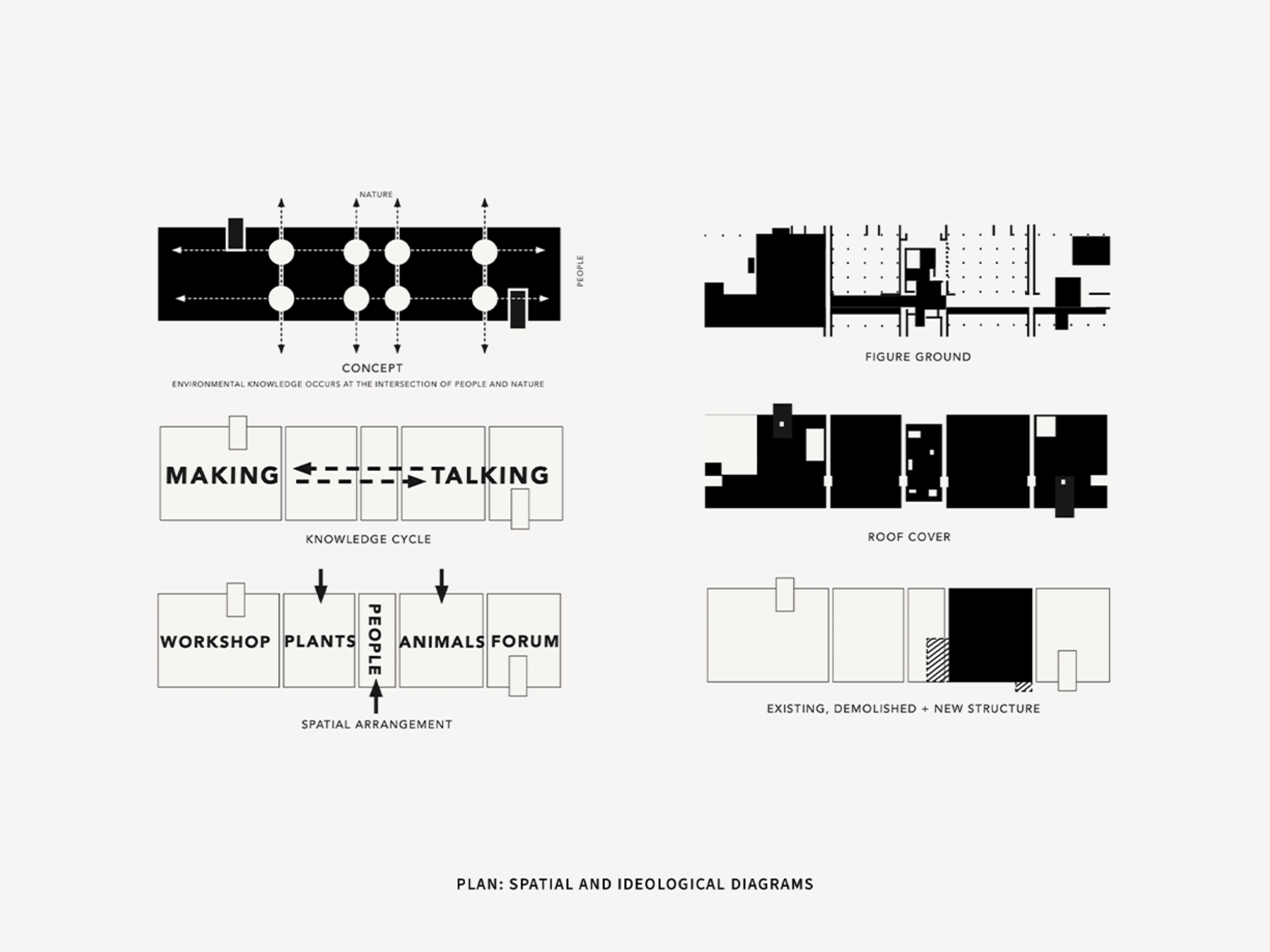

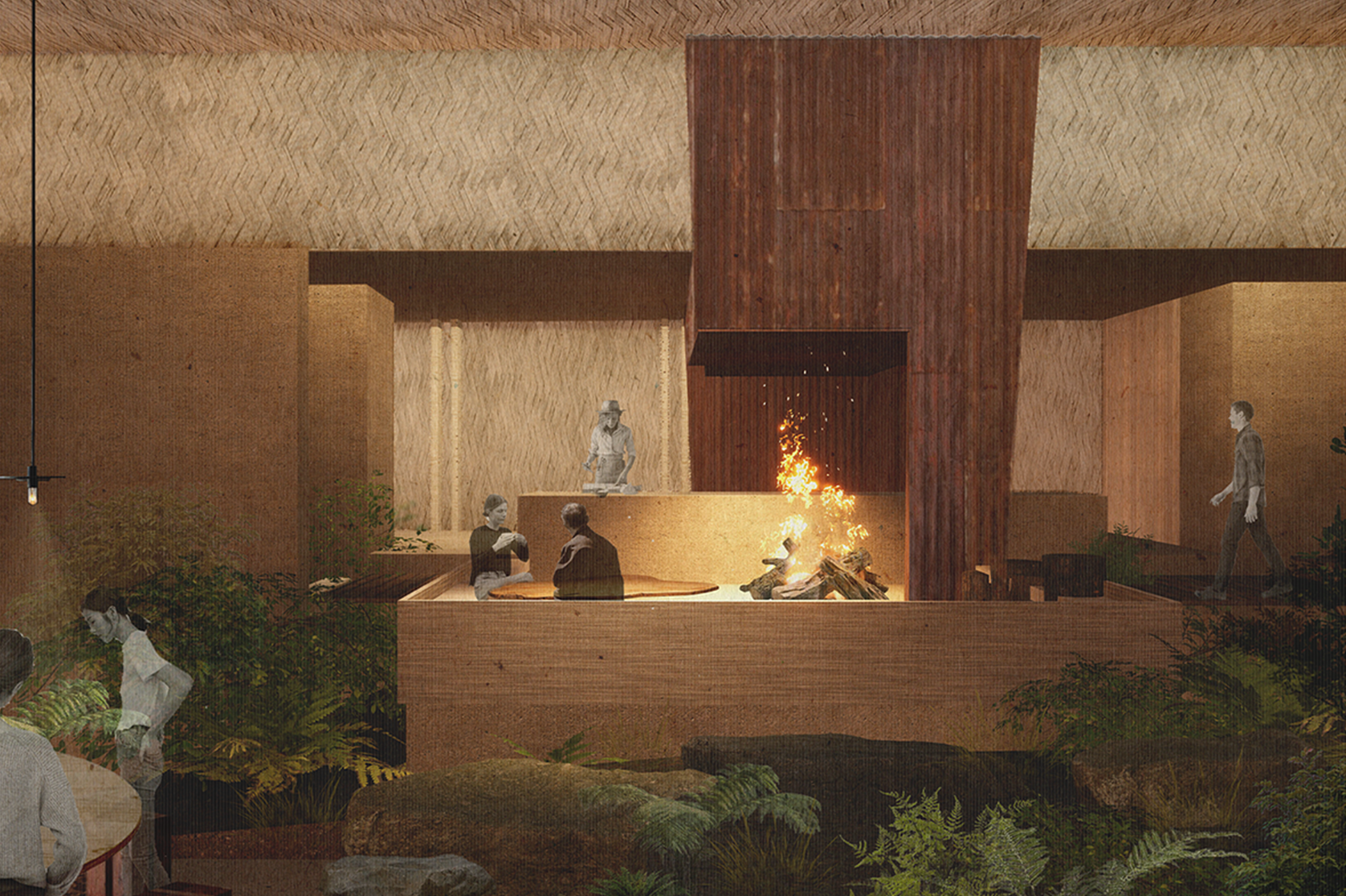

Common Ground is a response to a visceral feeling of concern for our world, advocating for heightened care towards the land, its people, and the future. Rooted in the turmoil of land management in Tairāwhiti, the research underpinning Common Ground suggests that when environmental knowledge is depleted, unsustainable practice ensues. The scheme aims to reverse this trend by reinvigorating vernacular knowledge in a tacit, hands-on manner, where spending time on the land is imperative. It asks, “if historic mistakes have led to the current environmental damage in Tairāwhiti, what process of healing must be undertaken as a remedy?”

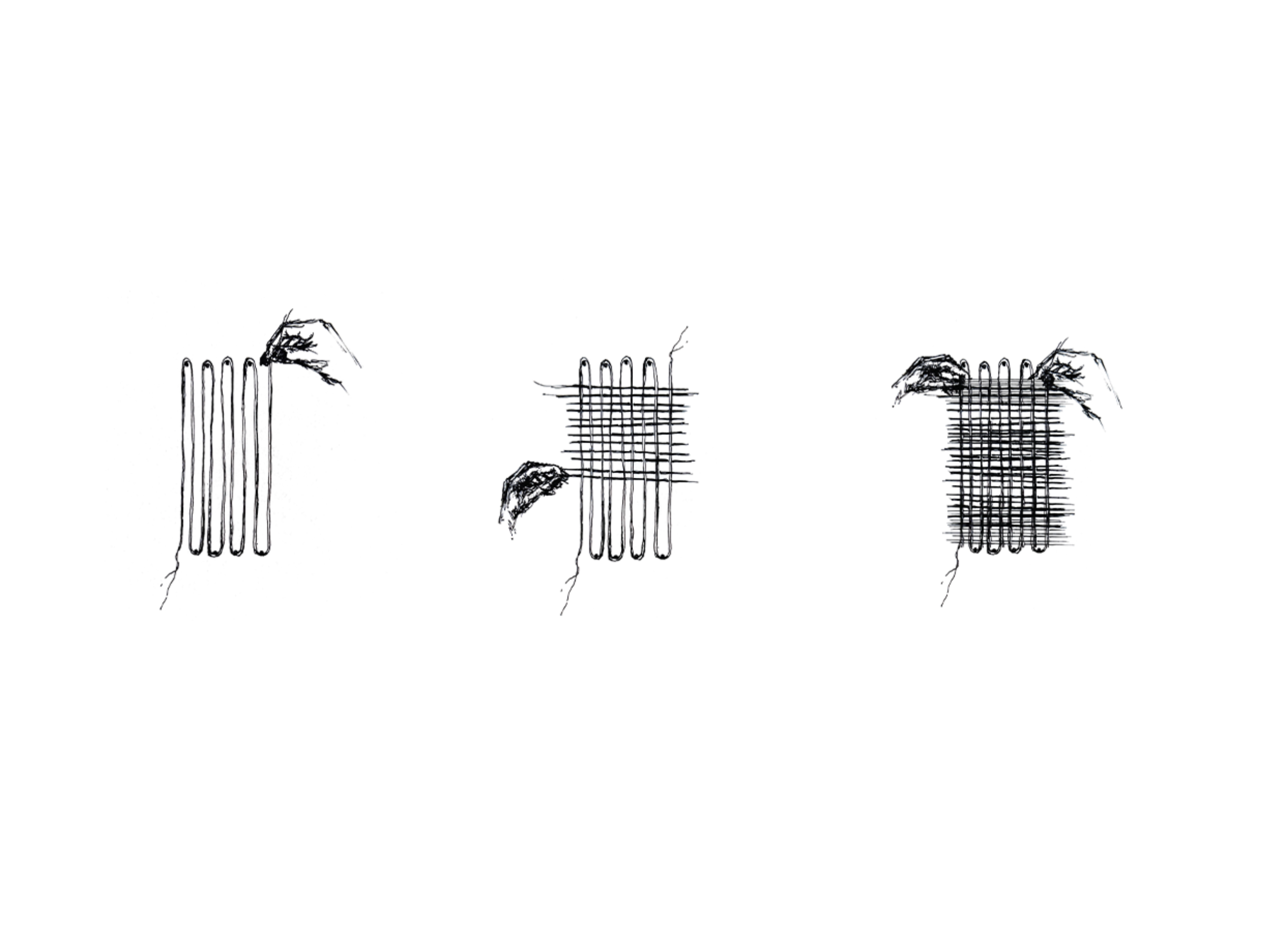

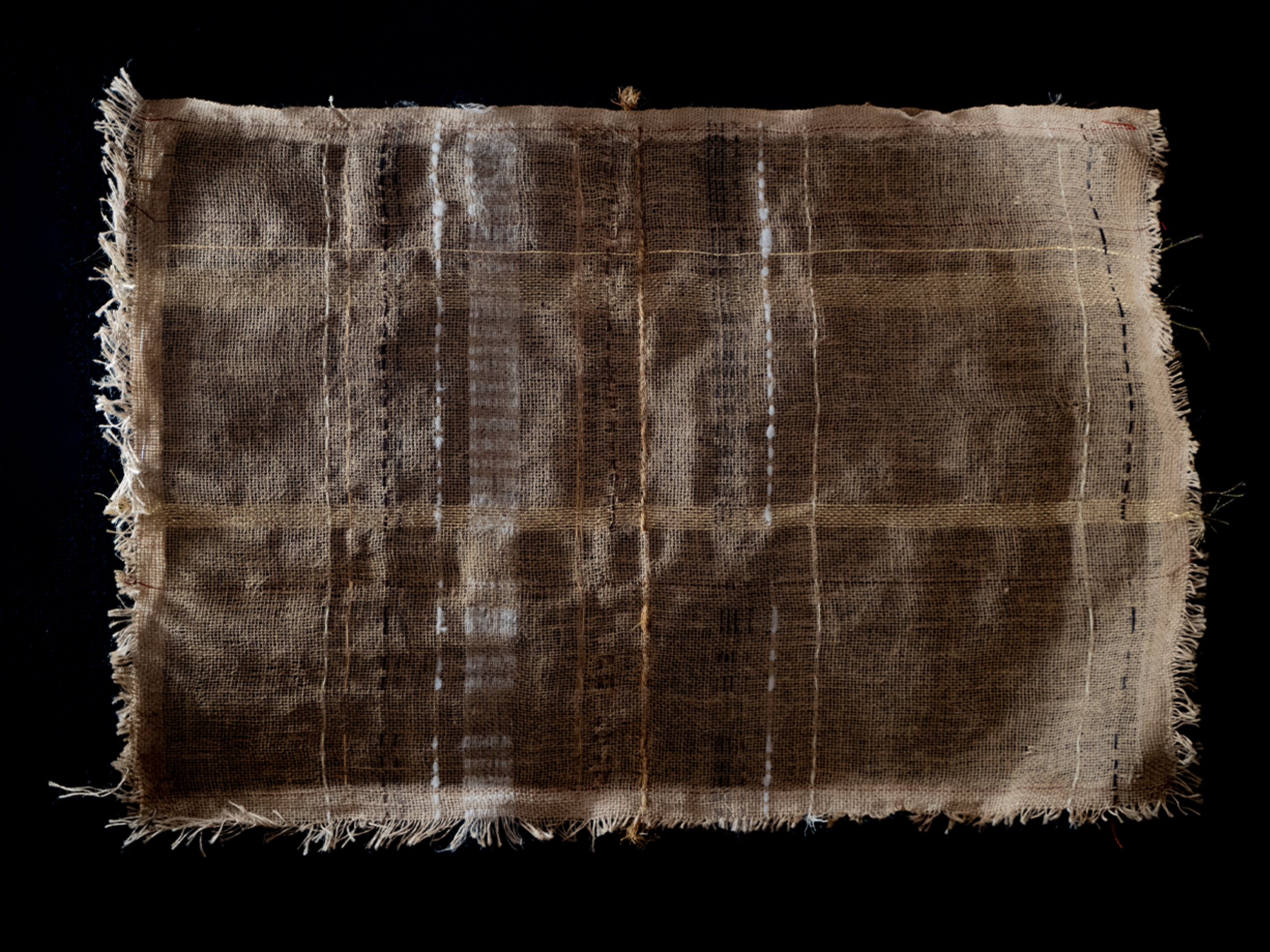

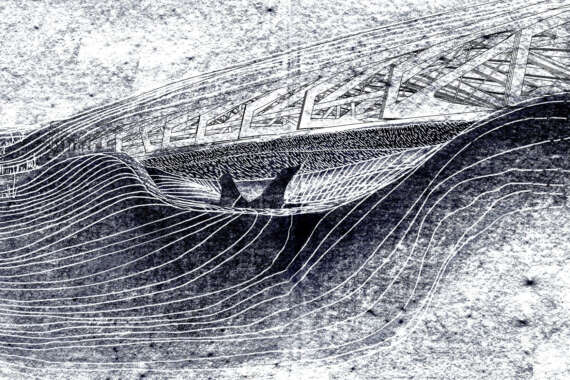

This project speculates on a future 'knowledge architecture' for a world grappling with environmental disaster. It is sited at Hiwiroa Station, a relative’s farm north of Tūranganui-a-kiwa Gisborne. The outcome is a 'forum for vernacular environmental knowledge': a regional touchpoint fostering the generation and proliferation of ideas. It aims to weave diverse knowledge strands together in a simplified, immersive space, seeking to strengthen the bond between people and land. It functions as an ideological hub, acting to galvanise local communities and businesses with the goal of achieving powerful collective environmentalism.

While it acknowledges the global nature of the challenge, Common Ground specifically addresses the unique coexistence of diverse knowledge strands within a colonised territory, emphasising the importance of uplifting marginalised knowledge of Aotearoa’s indigenous forest ecology."