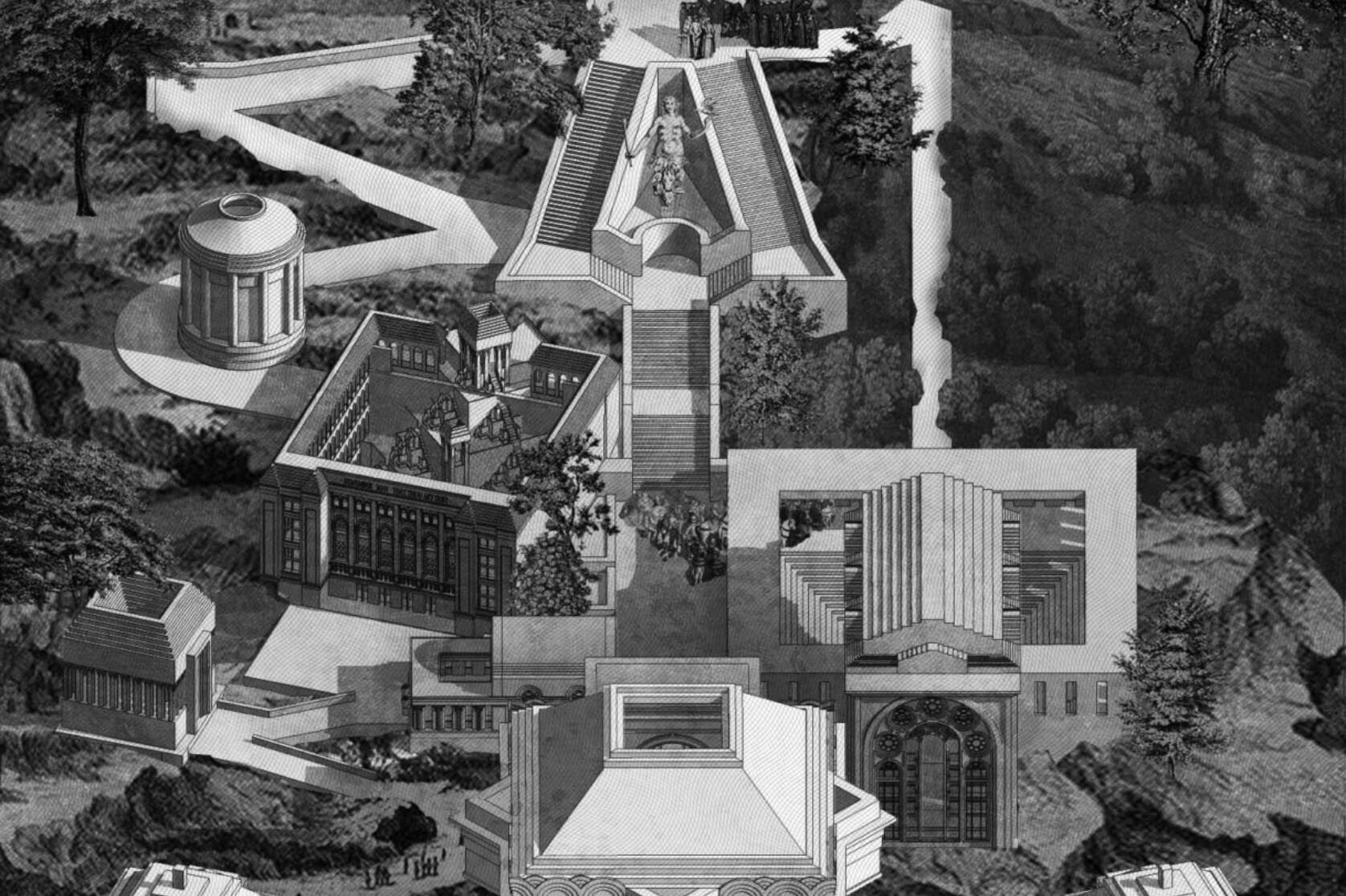

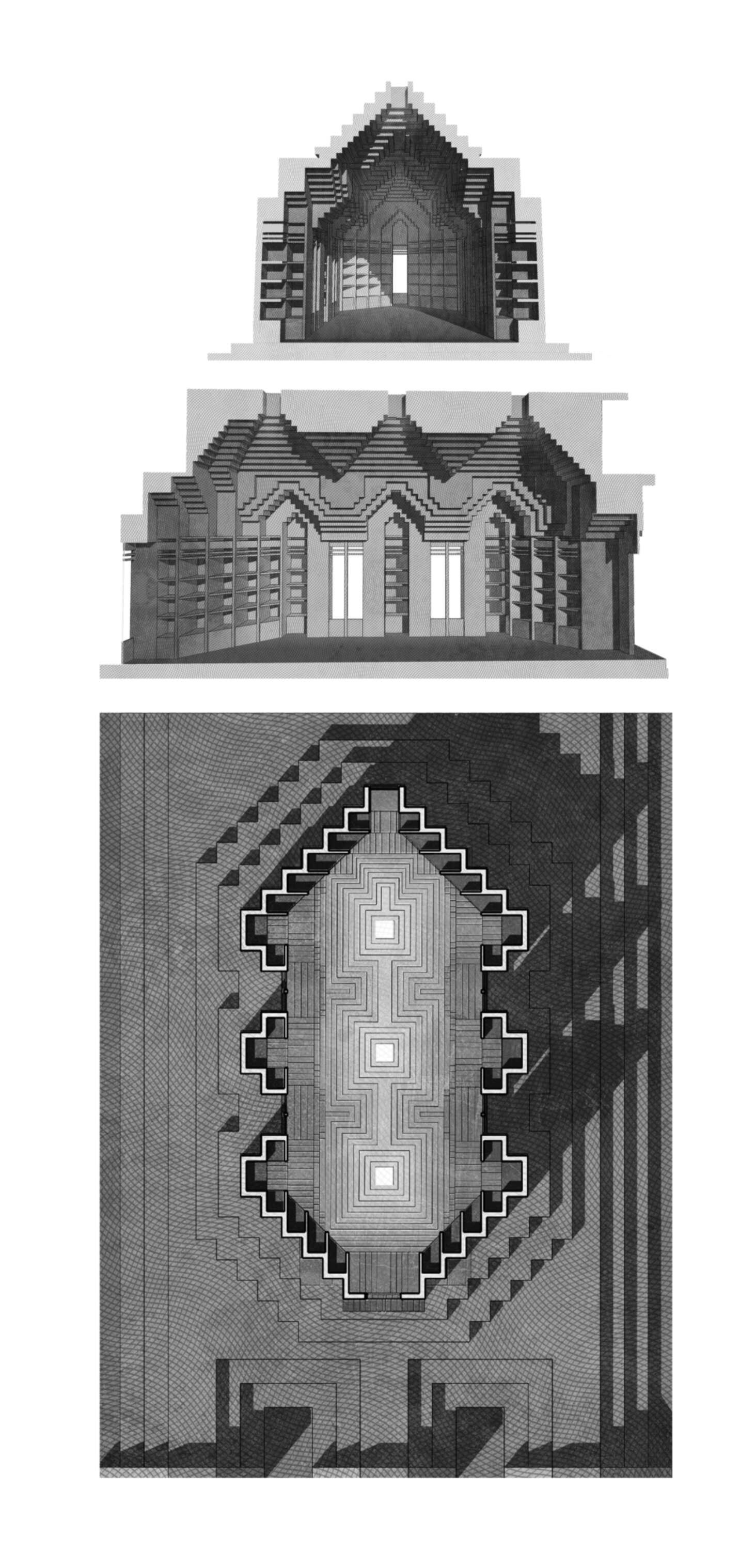

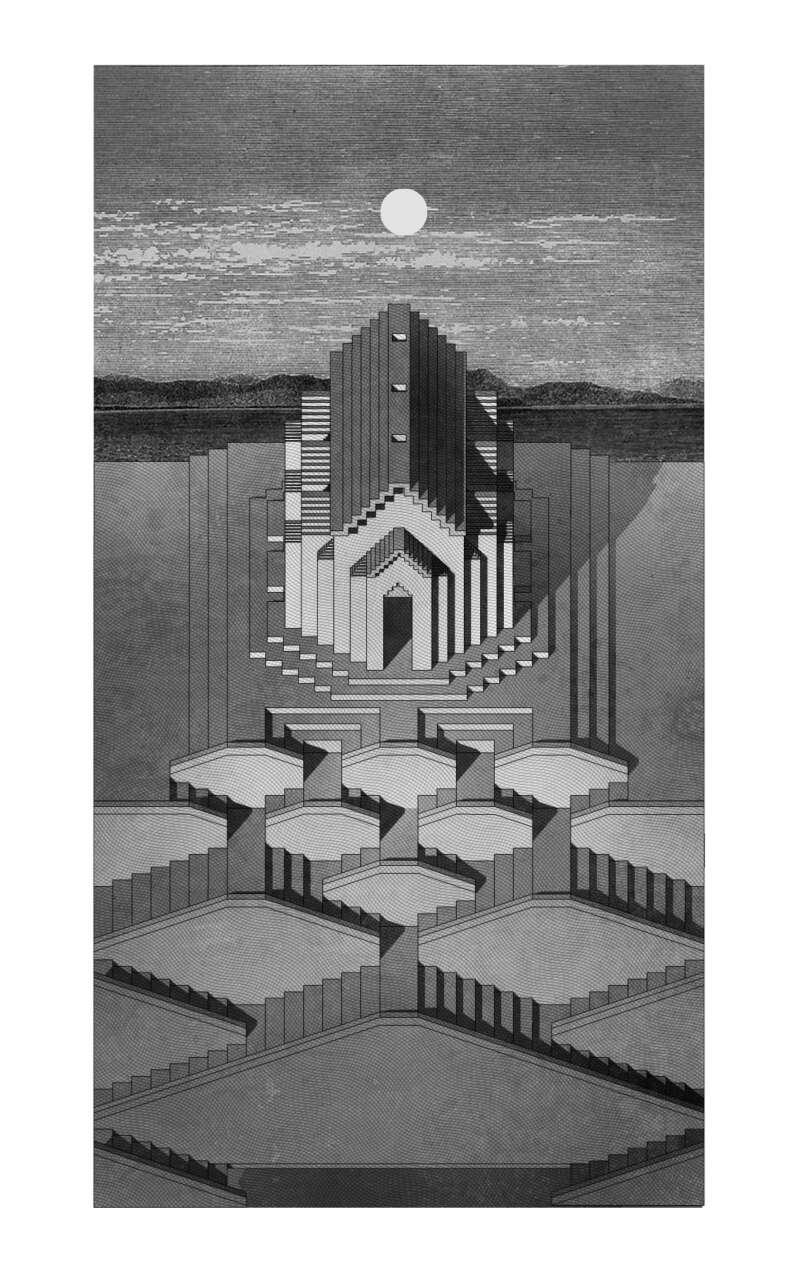

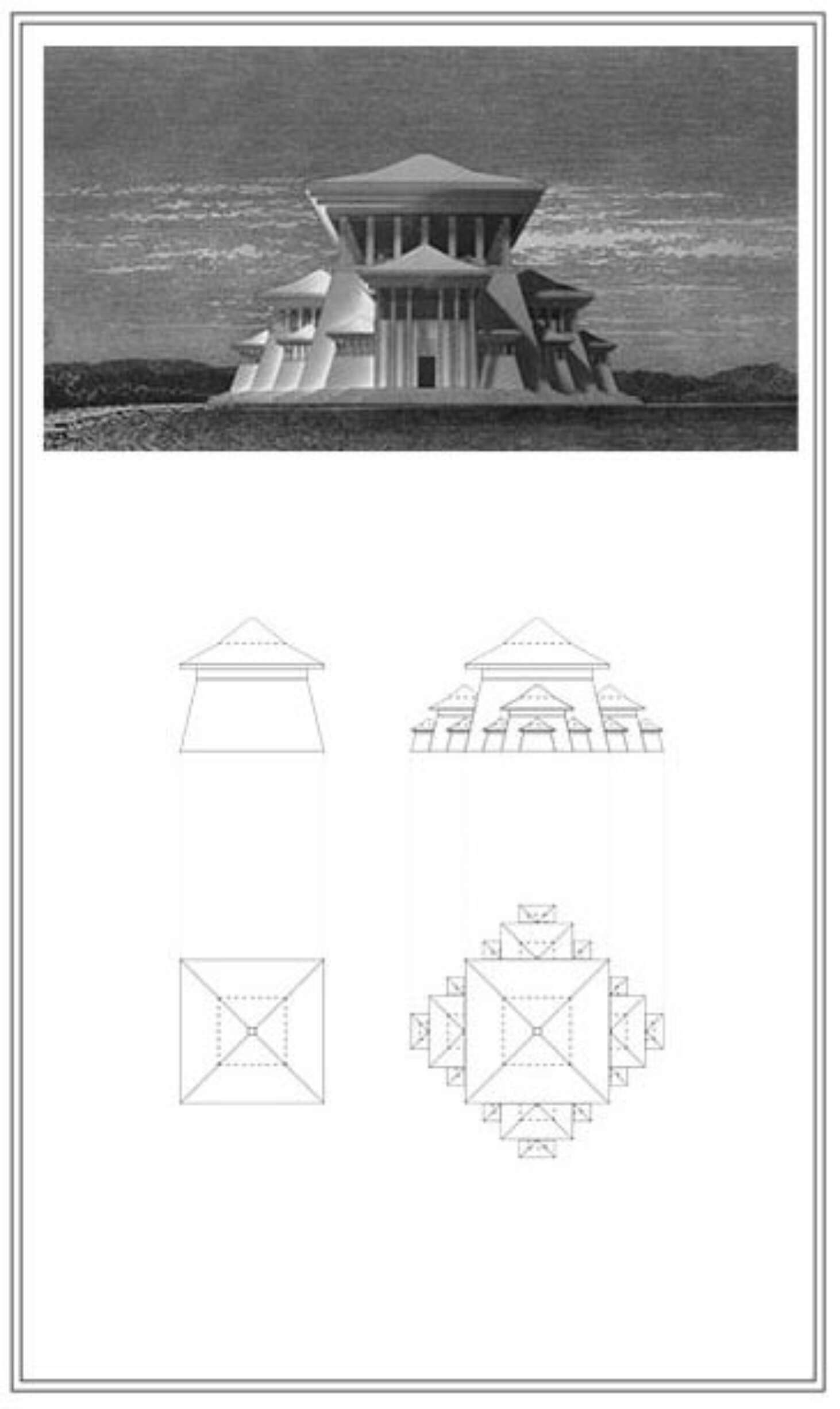

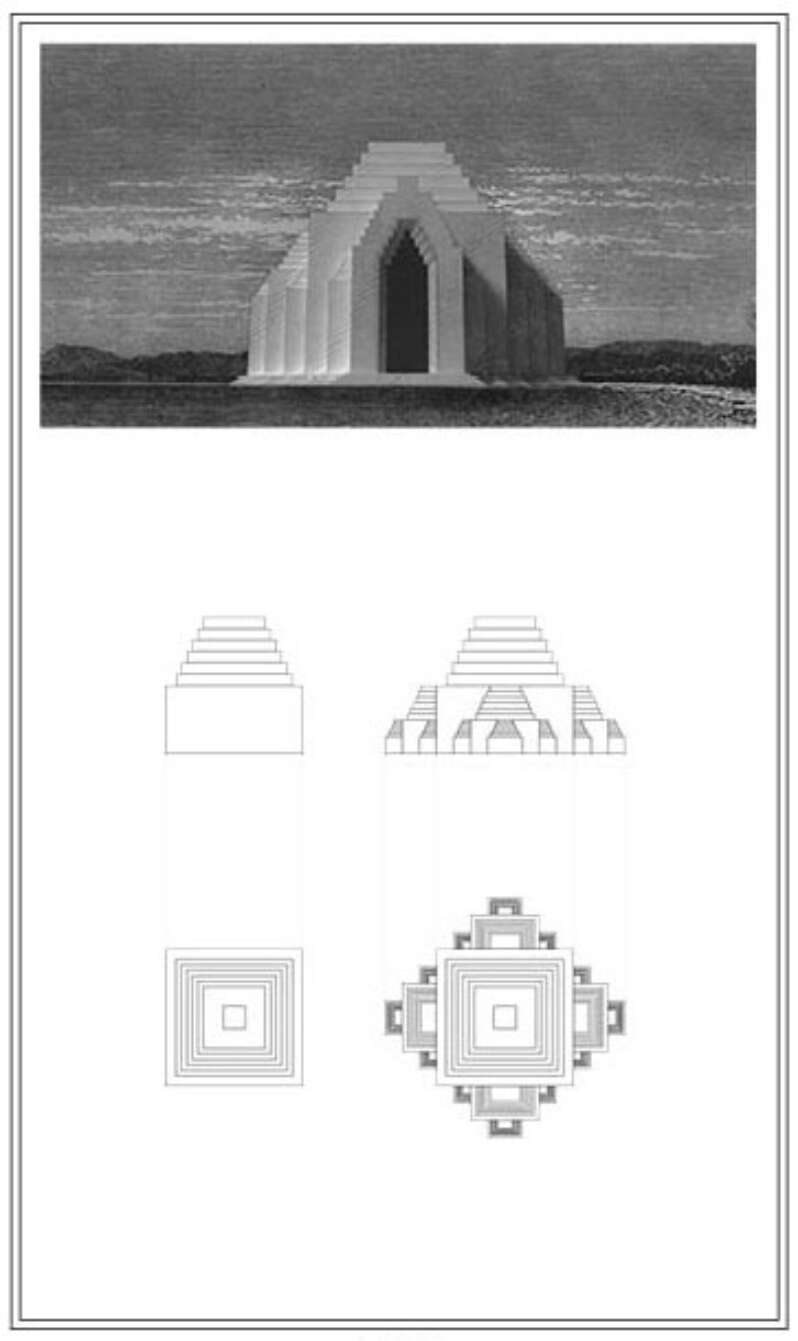

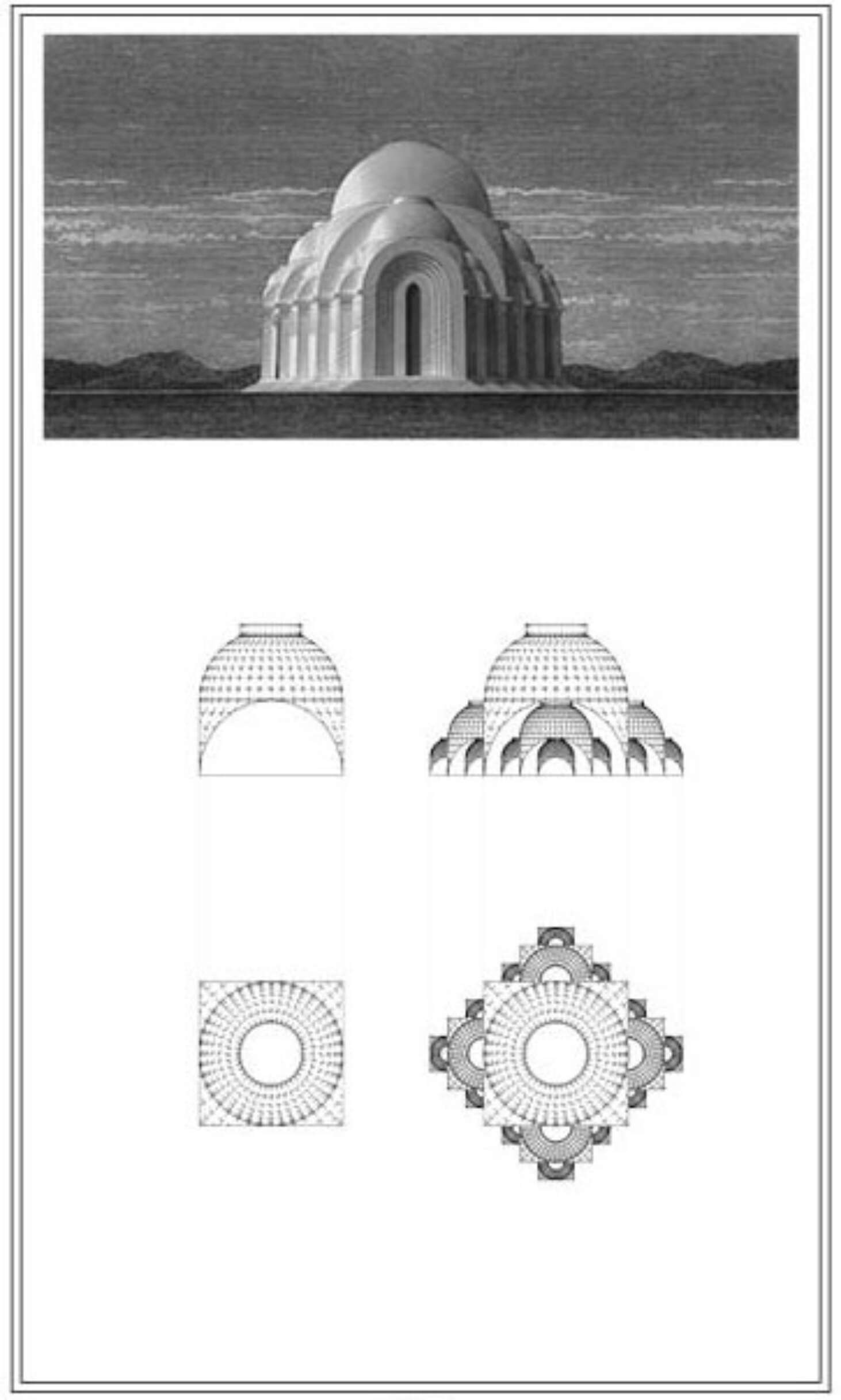

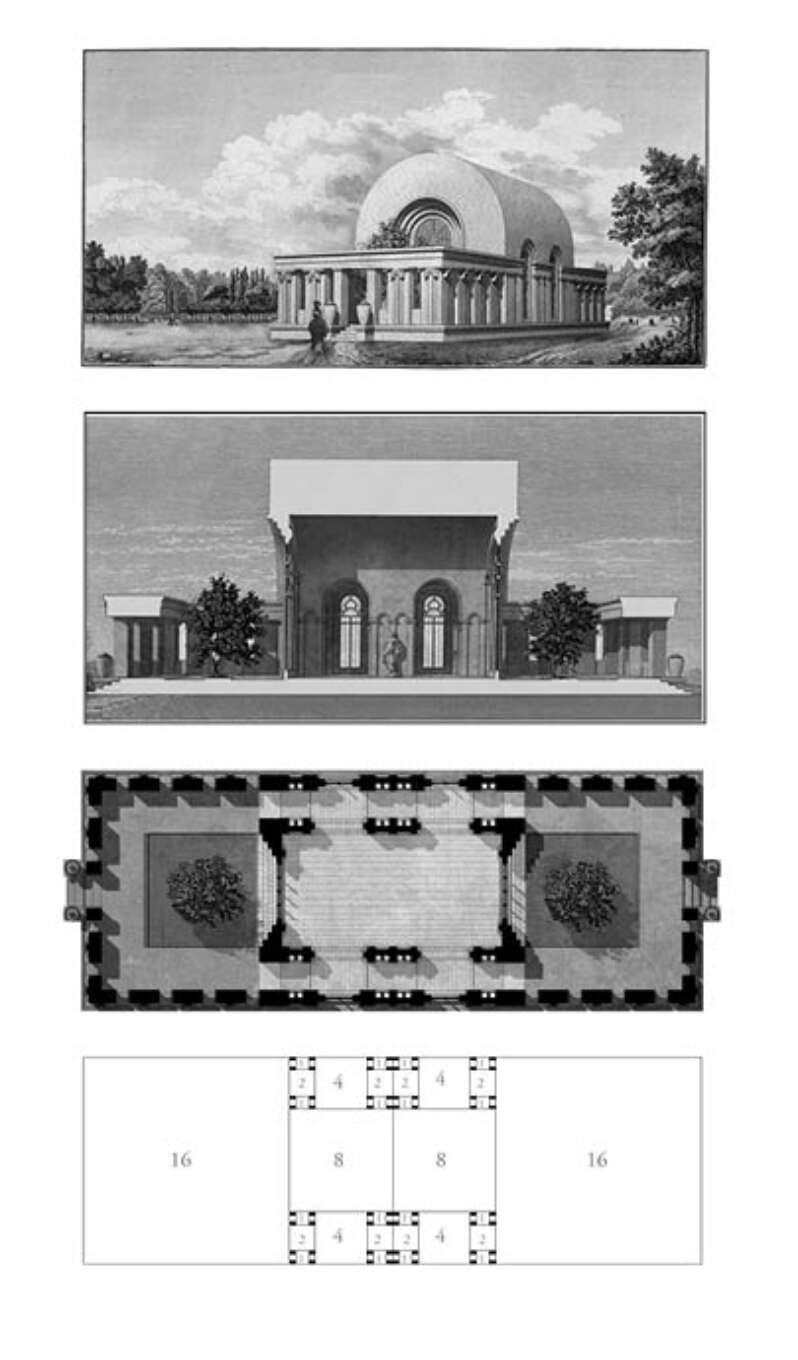

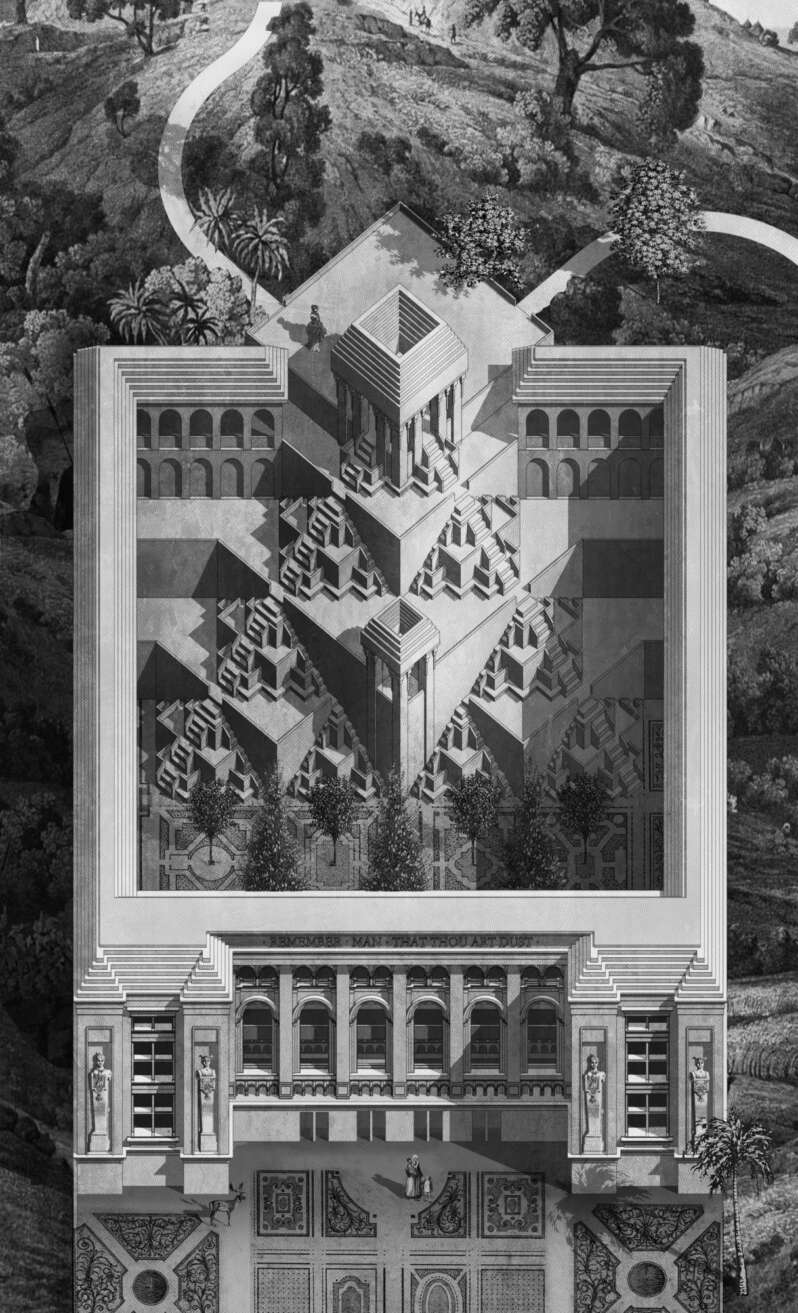

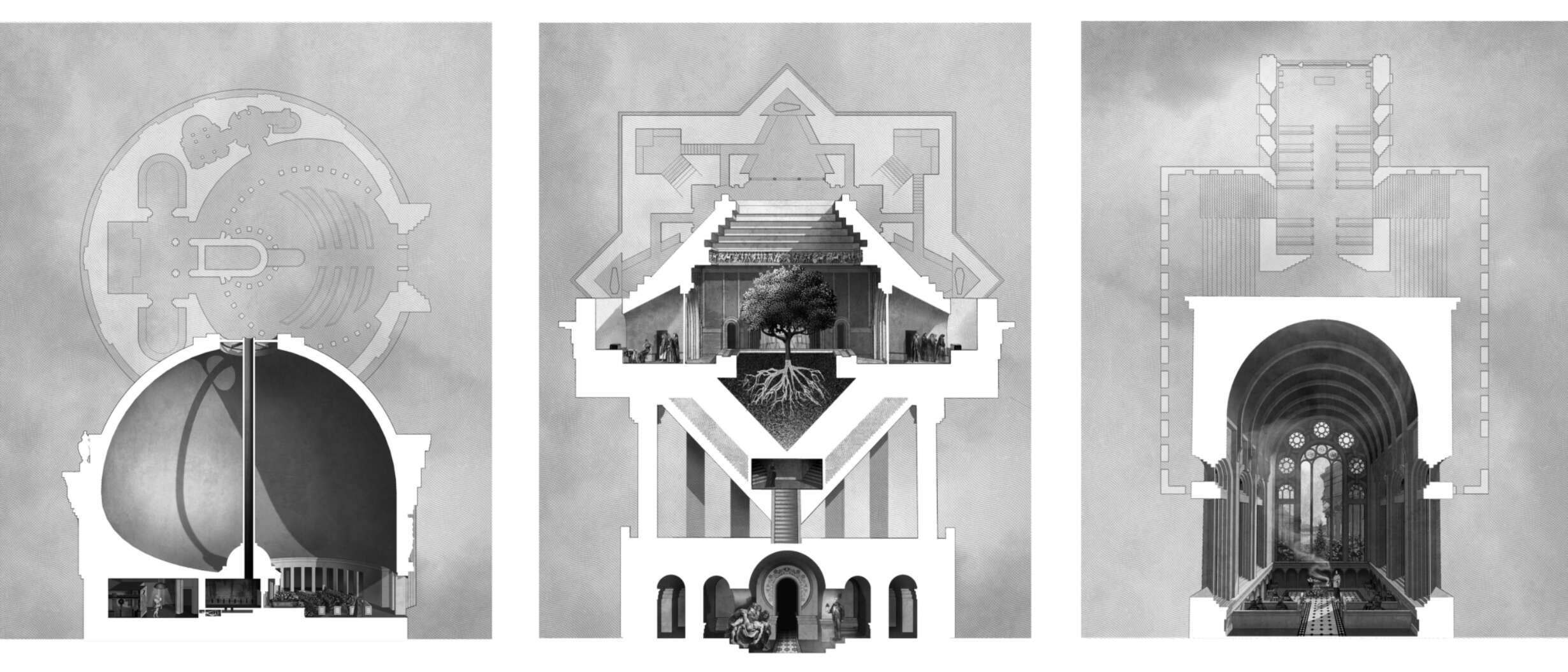

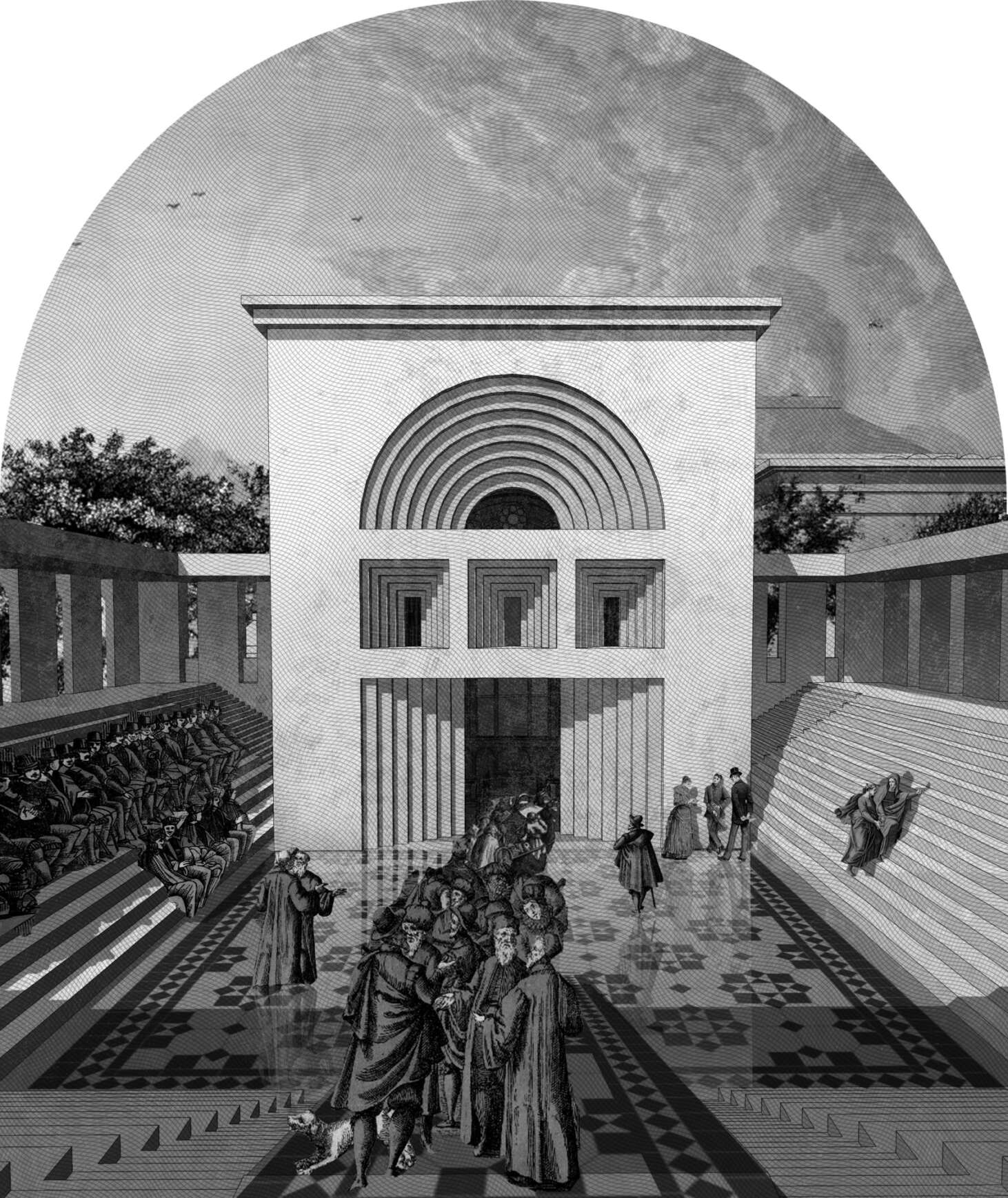

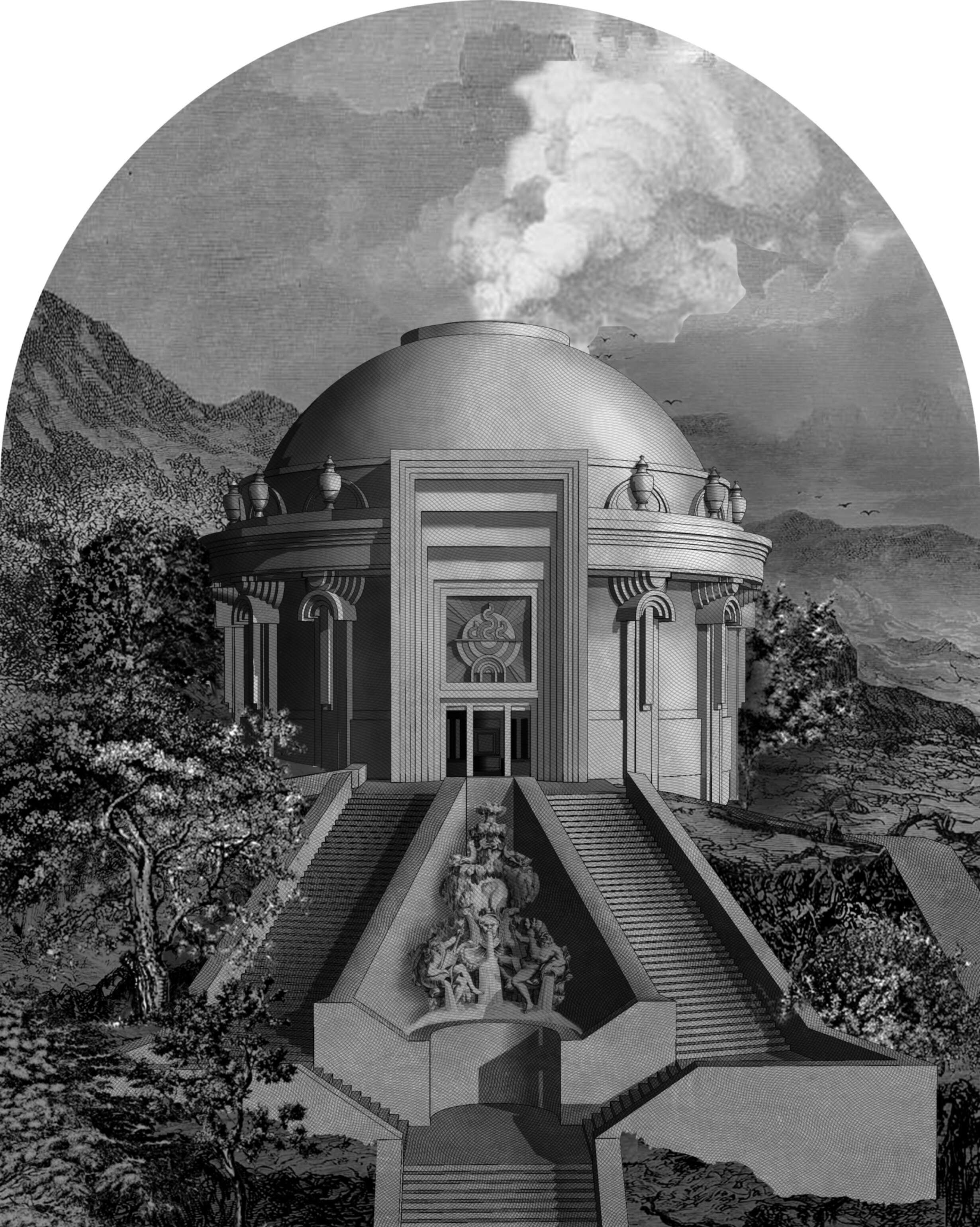

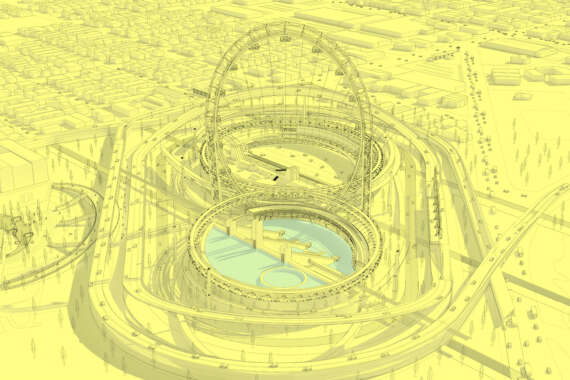

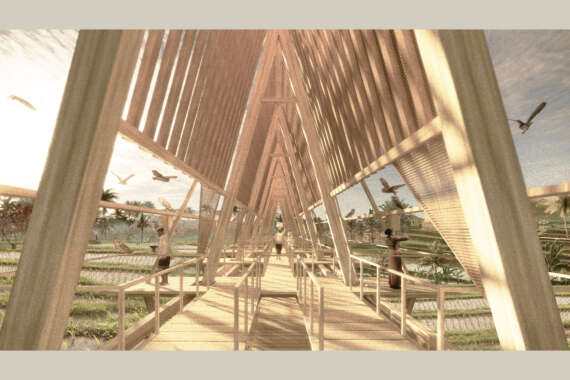

Here is another world: a world apart and a world of unfamiliar emotive power. We look into Daniel’s drawings and find architectural space at a heroic scale and mass at the same time that we see organisational legibility without a familiar economy of means.

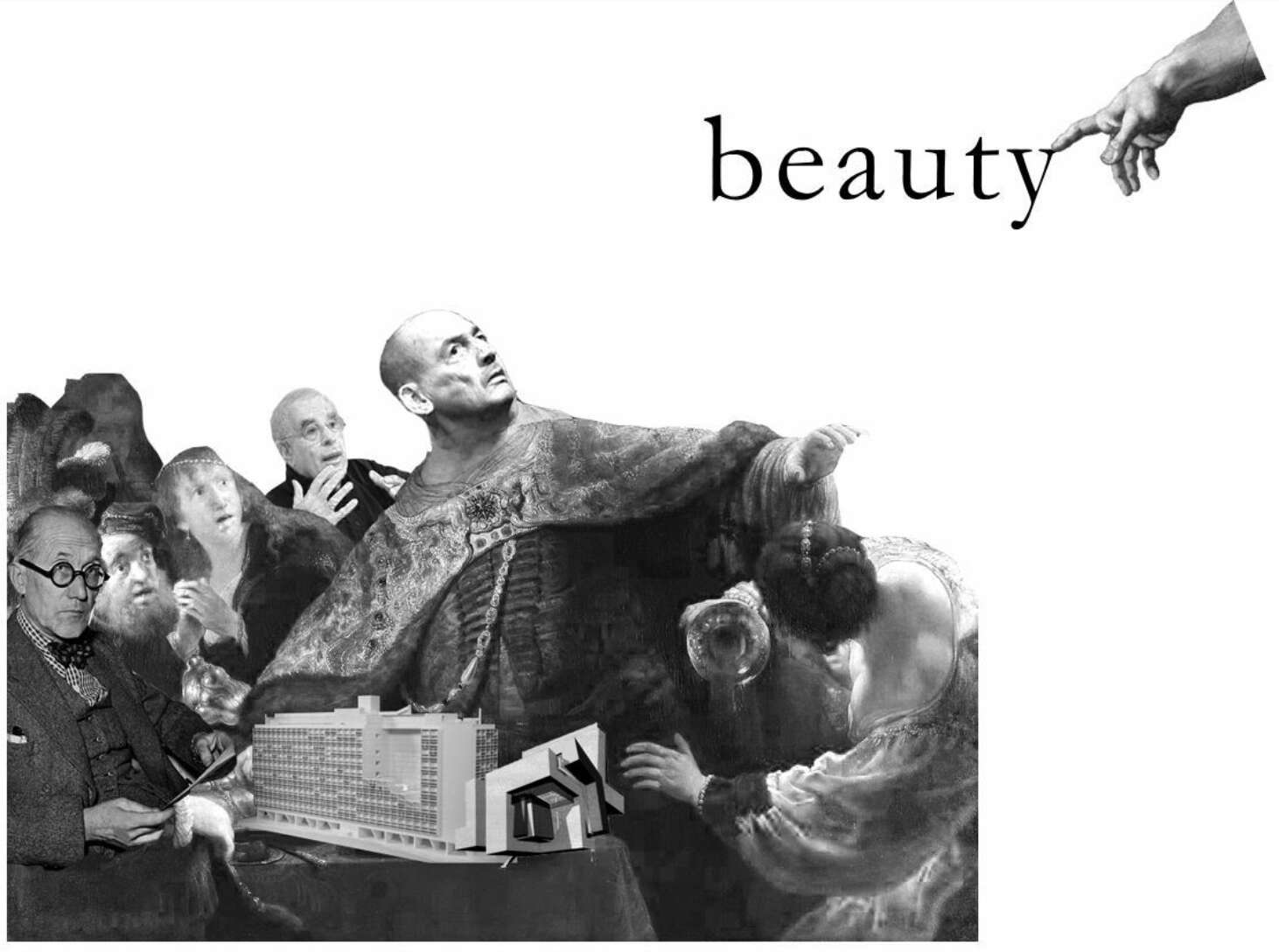

Daniel supplants the more well-trodden route of historical research into the philosophical discourse of beauty with neuropsychological research while undertaking an exploration of his propensity for a classical language of form. He argues convincingly, based on recent scholarly scientific research, that, without reference to optically-visual perception, we are neurologically inclined to find certain regular forms ‘more pleasing’, as he puts it: those that are asymmetrical.

In developing forms which manifest these aesthetic and formal obsessions, Daniel assumed normative modern and classical modes of representation towards a world of surreal-classicism which hybridised science and tradition, recalling the 17th century querelle des Anciens et Modernes medico-archaeological background. Here, the monumental funerary complex Daniel presents as a means by which to explore ‘the beautiful’ explores a very new and personal classicism even if the figures which populate his extraordinary graphical world suggest otherwise. Programmatically the thesis imagines sublime and very public death rituals which, perhaps more than anything, seem in the very strange first months of 2020, appropriately apocalyptic.

— Michael Milojevic, supervisor