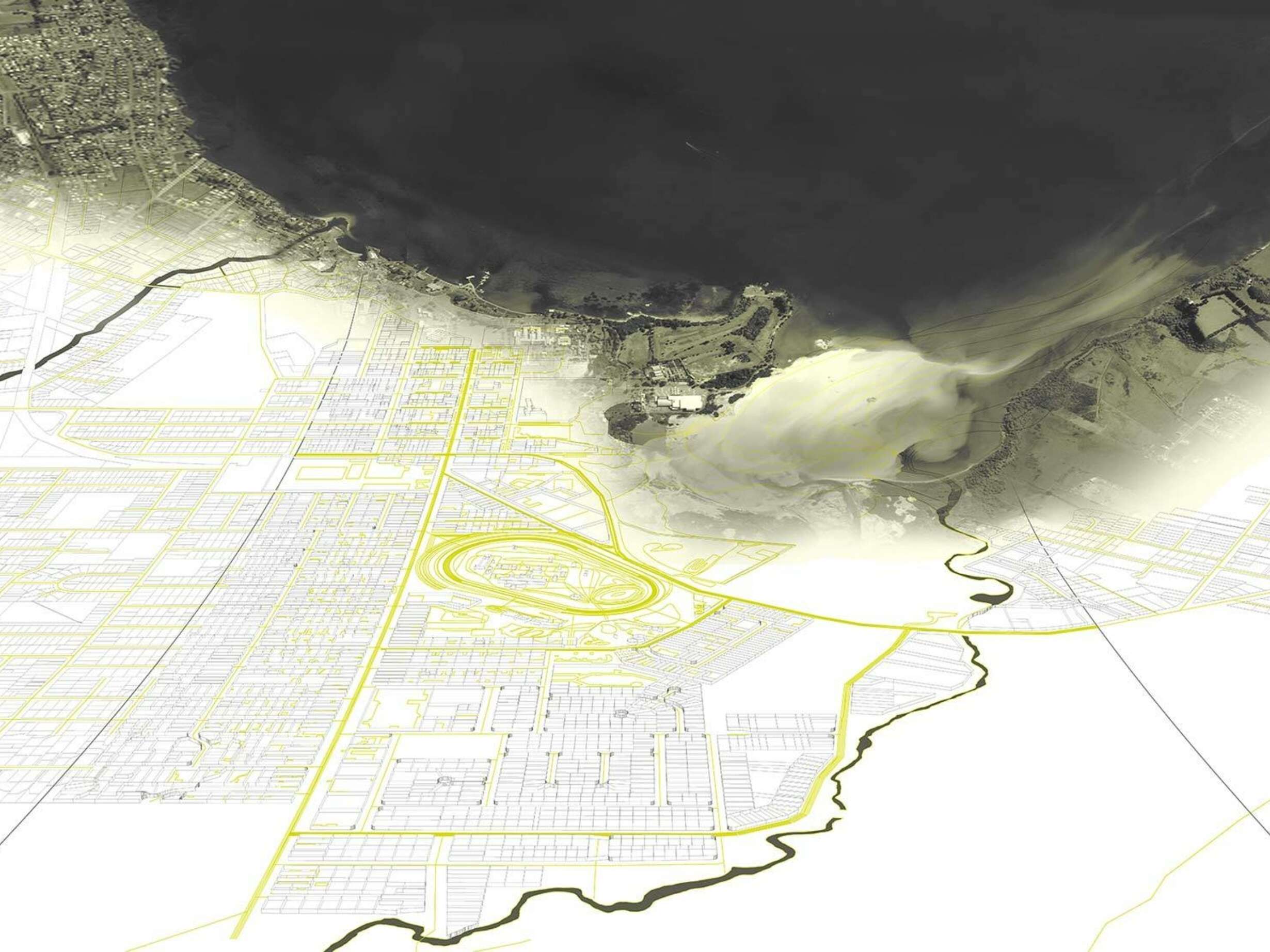

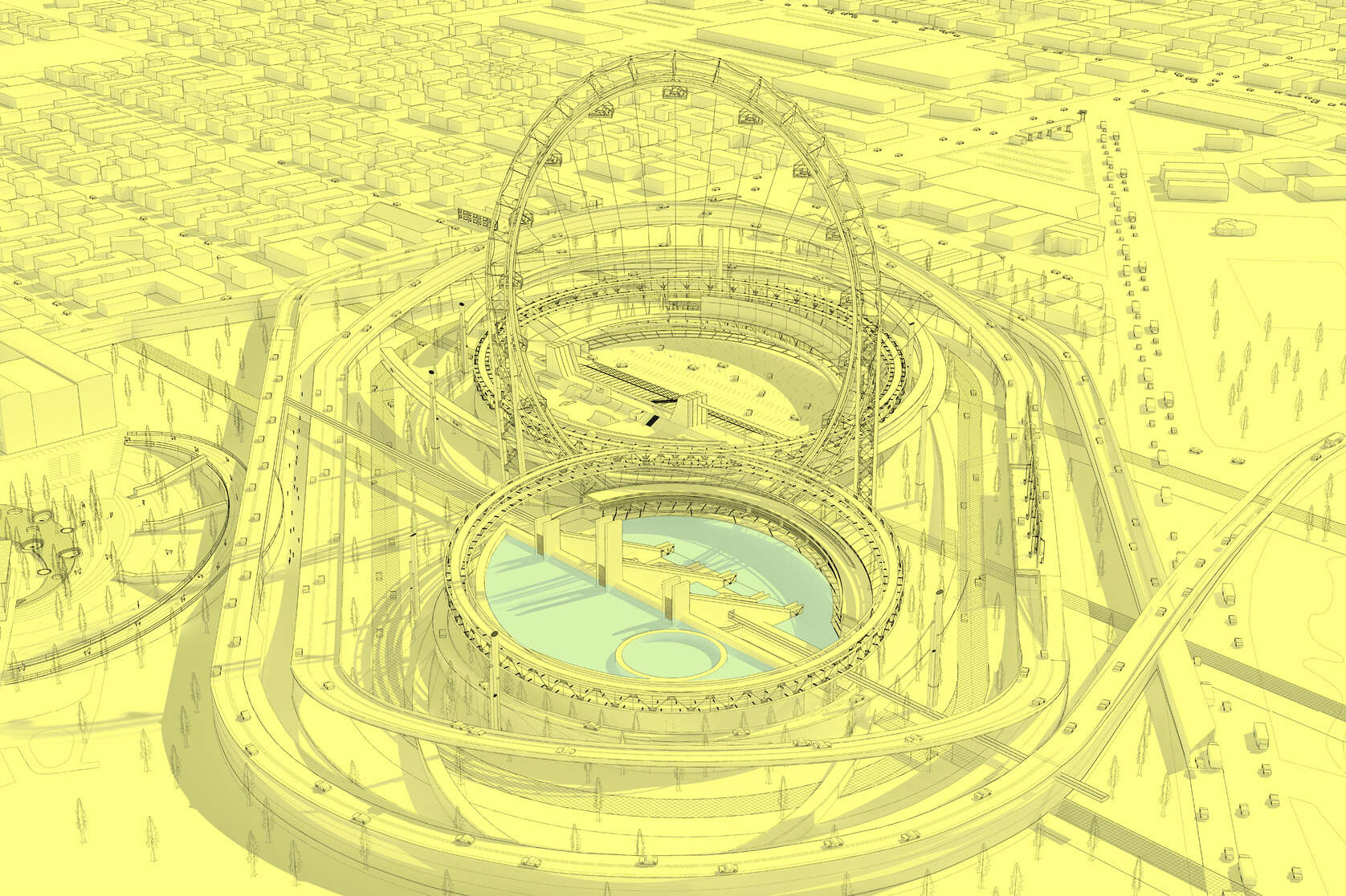

Rotovegas: Playground of Flux

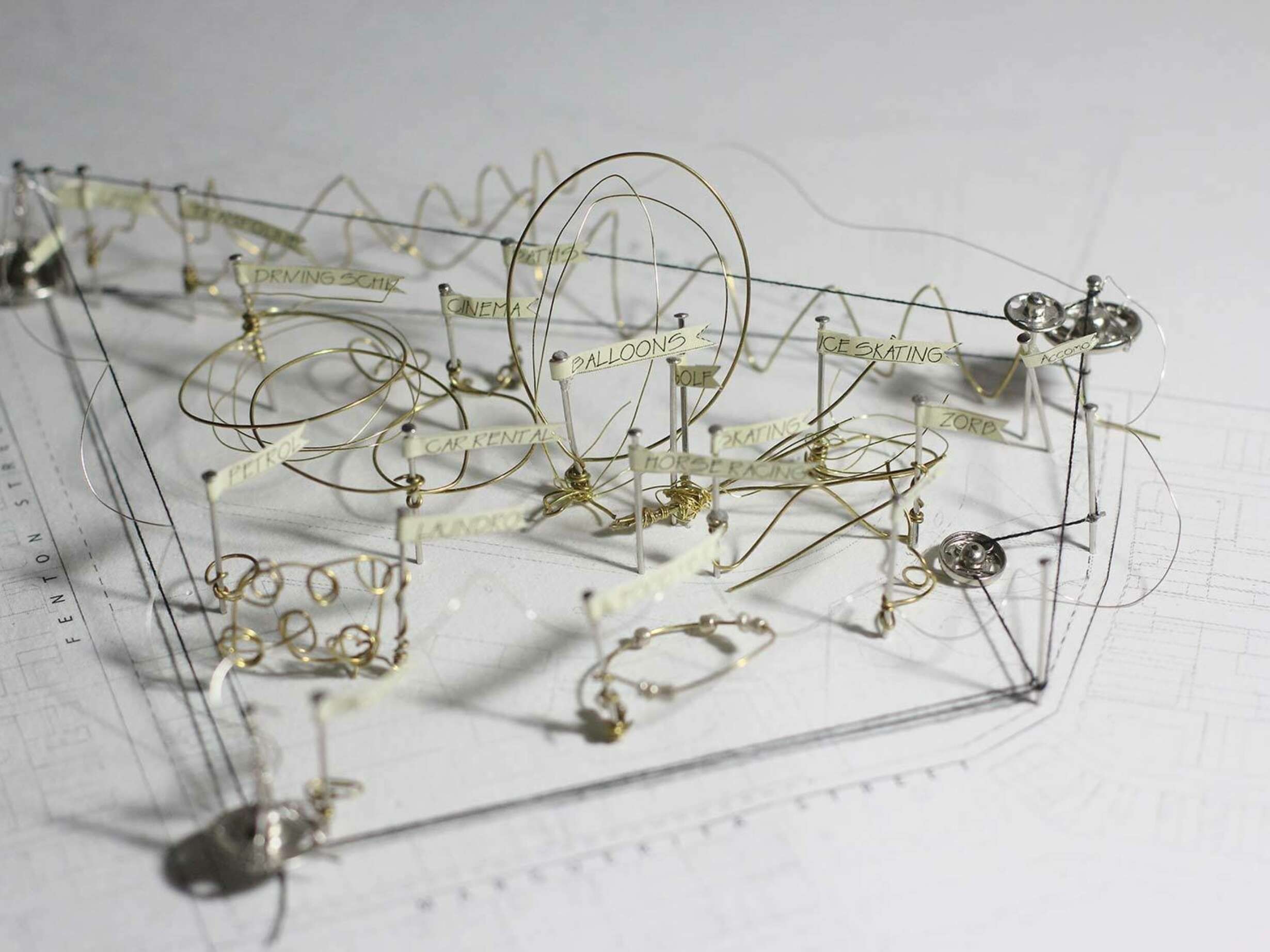

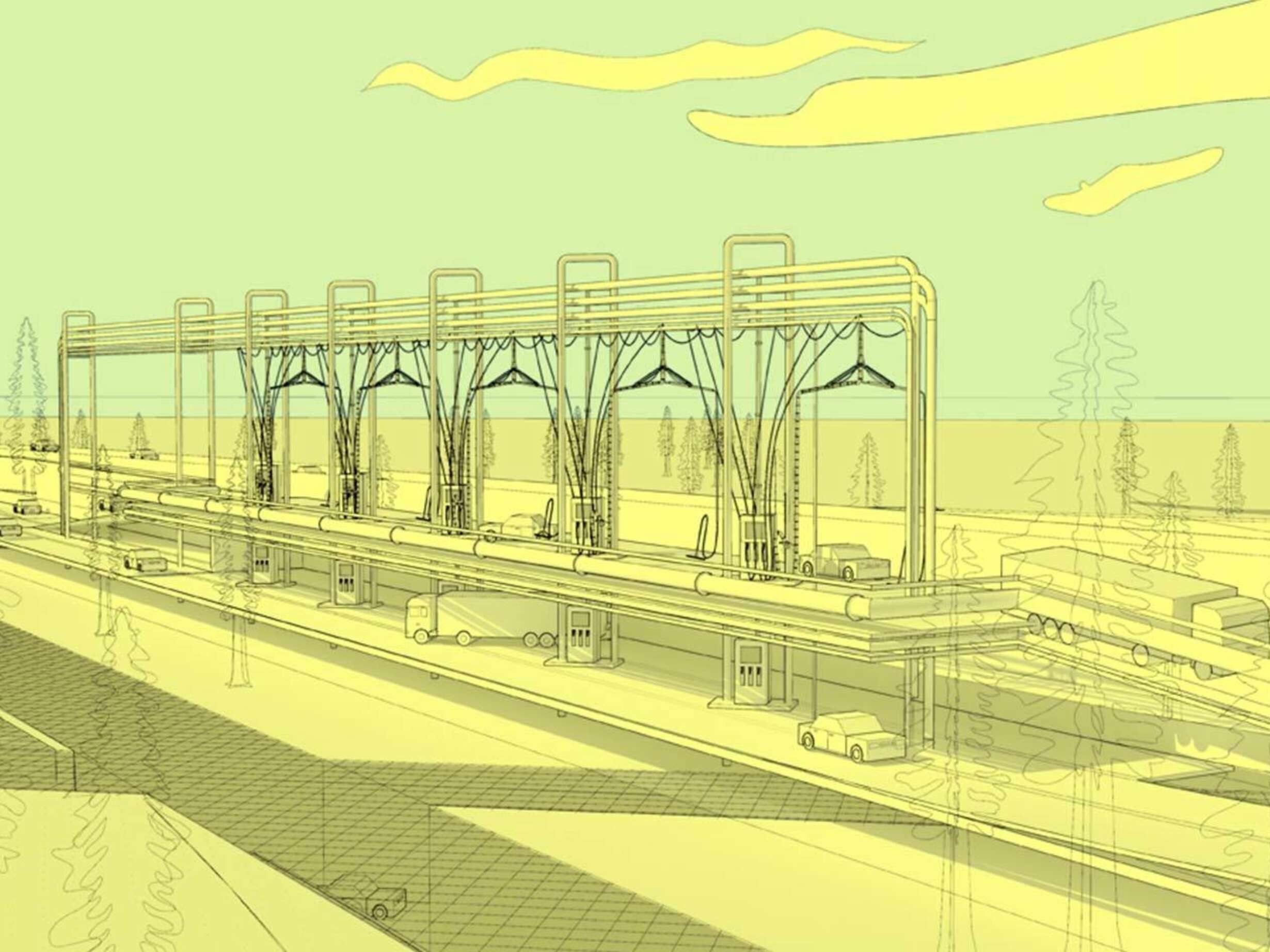

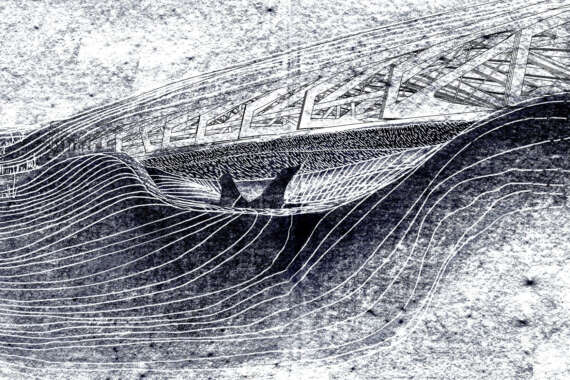

In a realm conceived of volumes and speeds, it is surprising how architectural infrastructure is often overlooked, being considered instead as benign conduits that serve passively alongside their building counterparts. Perhaps due to this apathy in terms of design, an authoritarian order, made up of road signs and road hierarchies, is left to dominate current infrastructural systems. This rigid order tends to produce reductive repercussions that are monotonous and utilitarian, potentially creating a society of automatons obediently following instructions set on aluminium spears lodged into the ground.

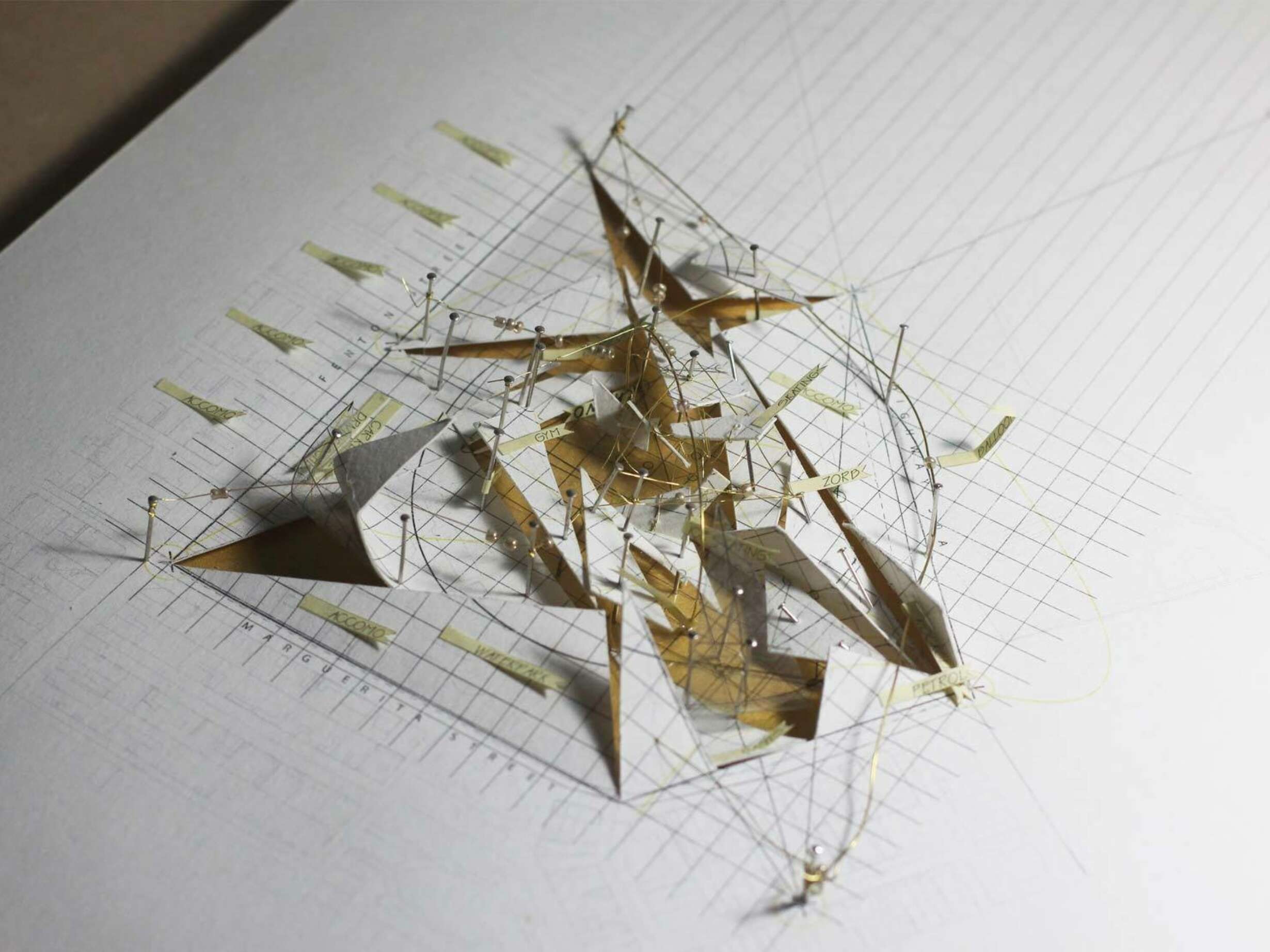

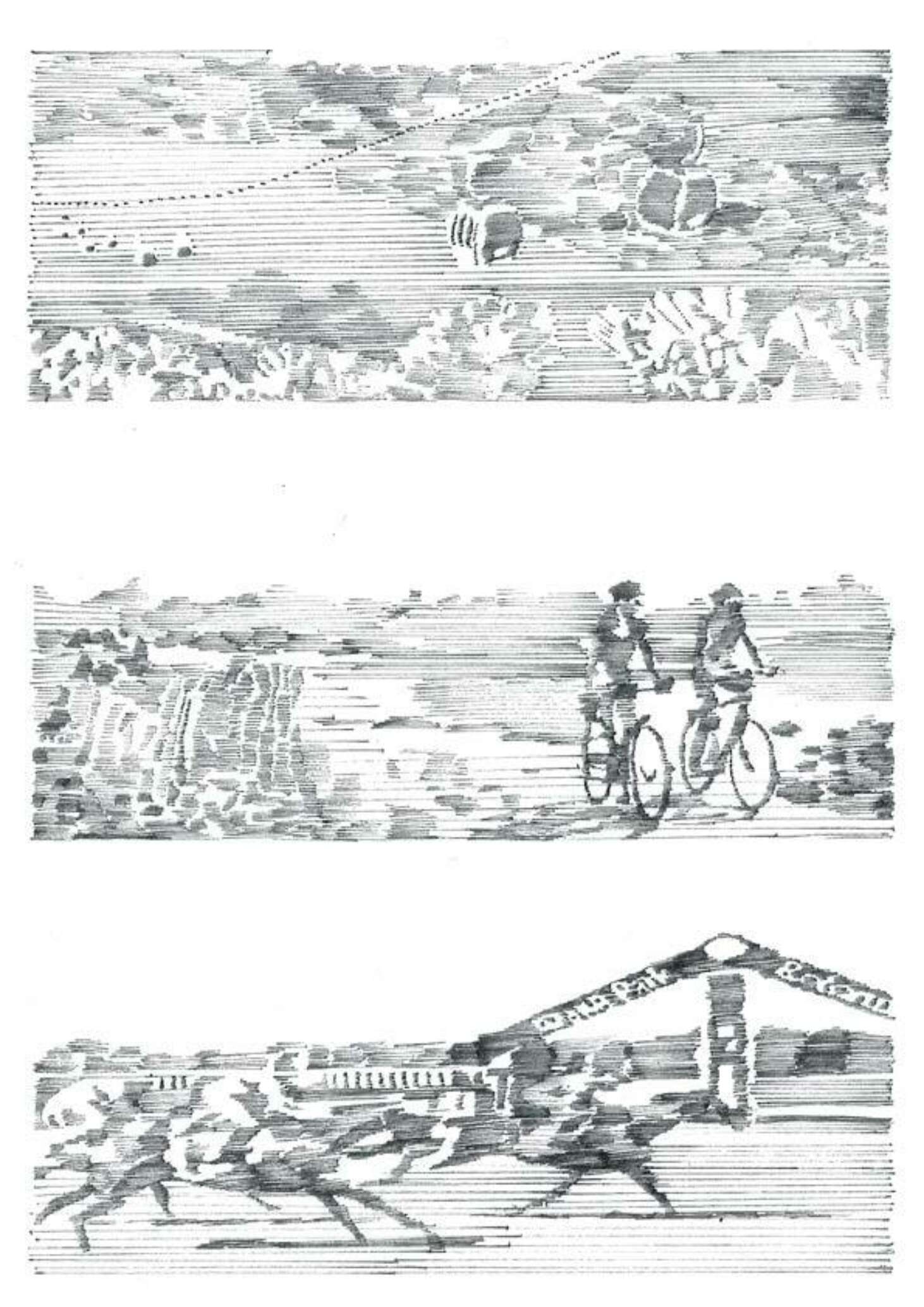

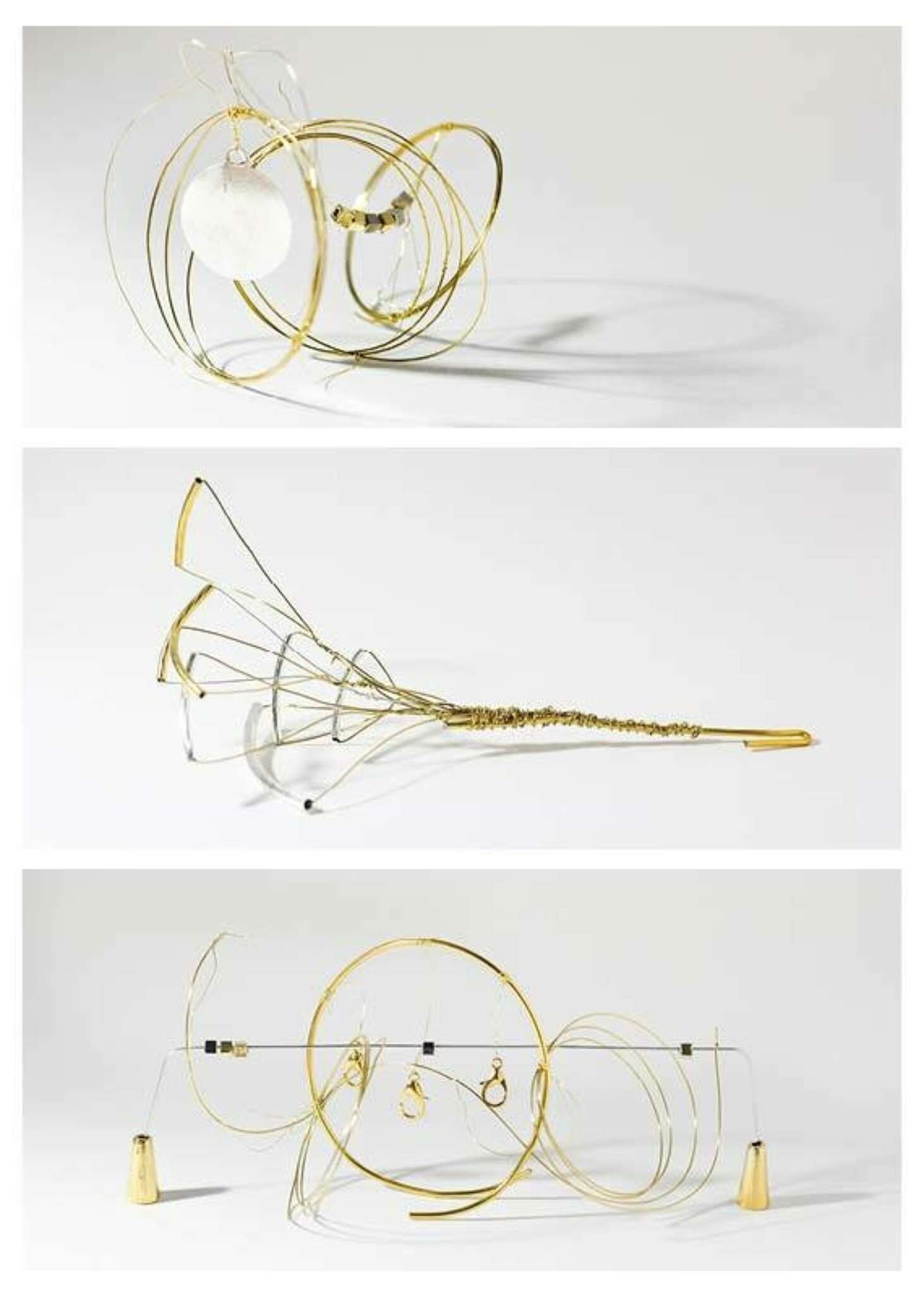

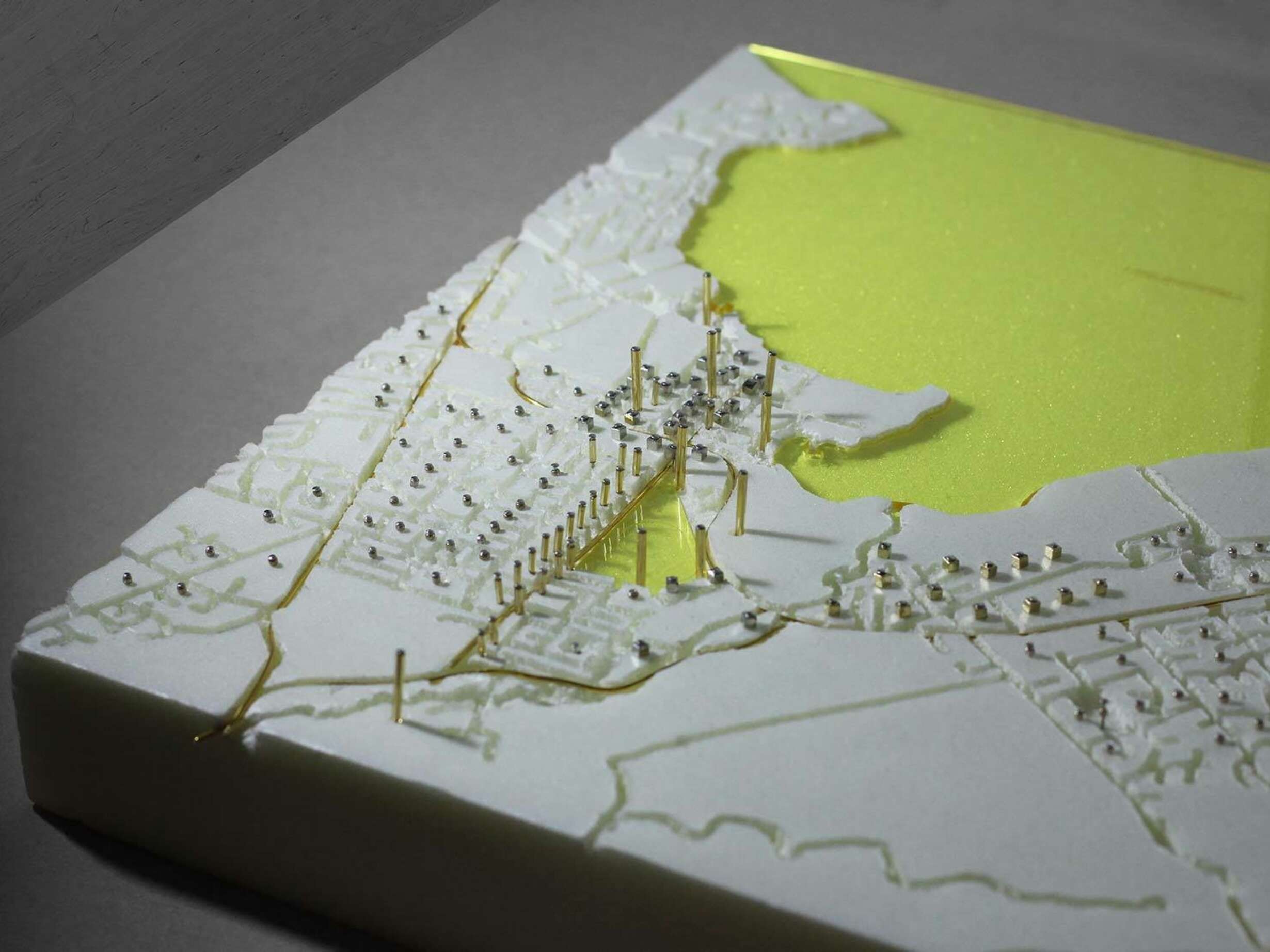

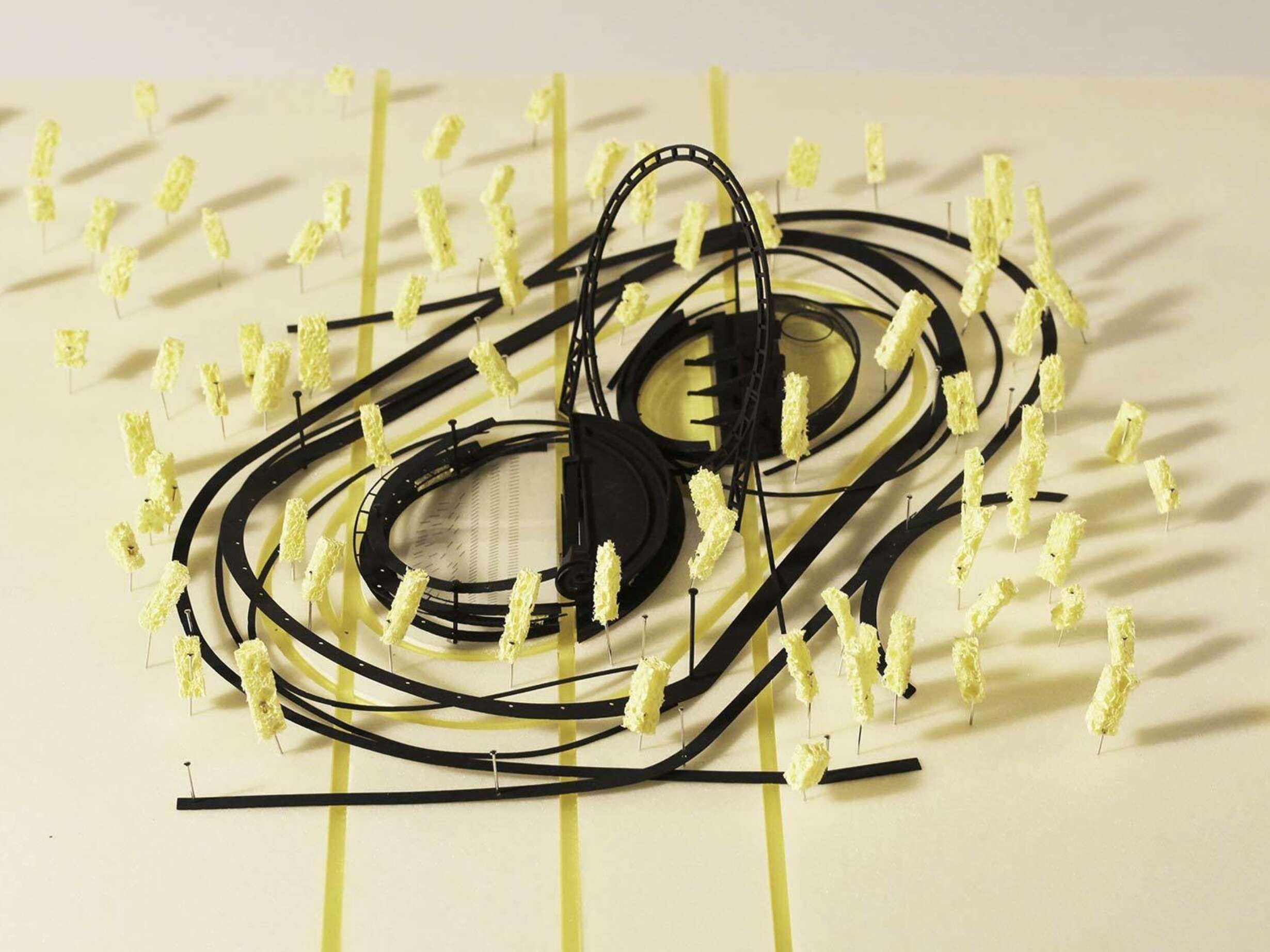

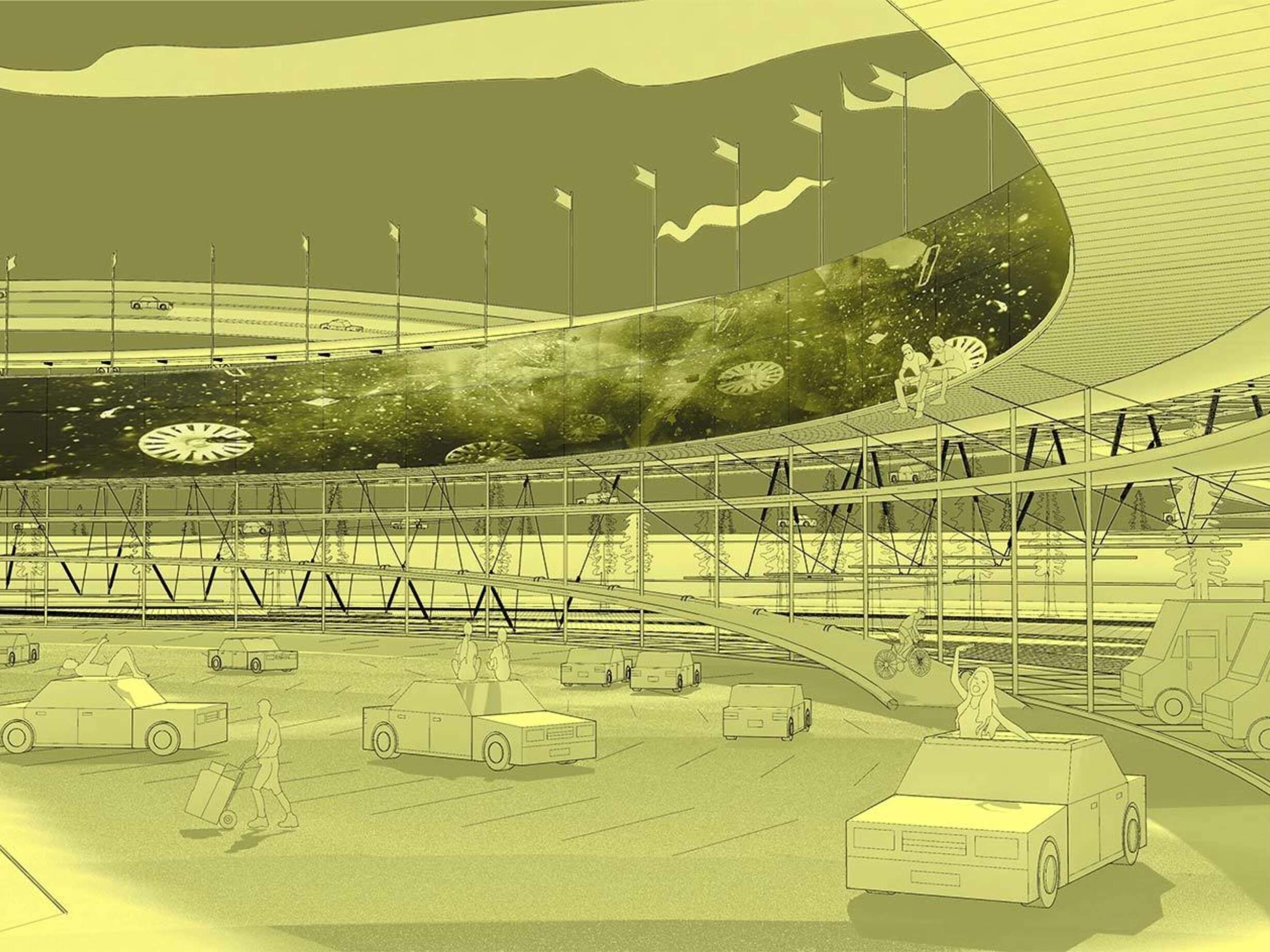

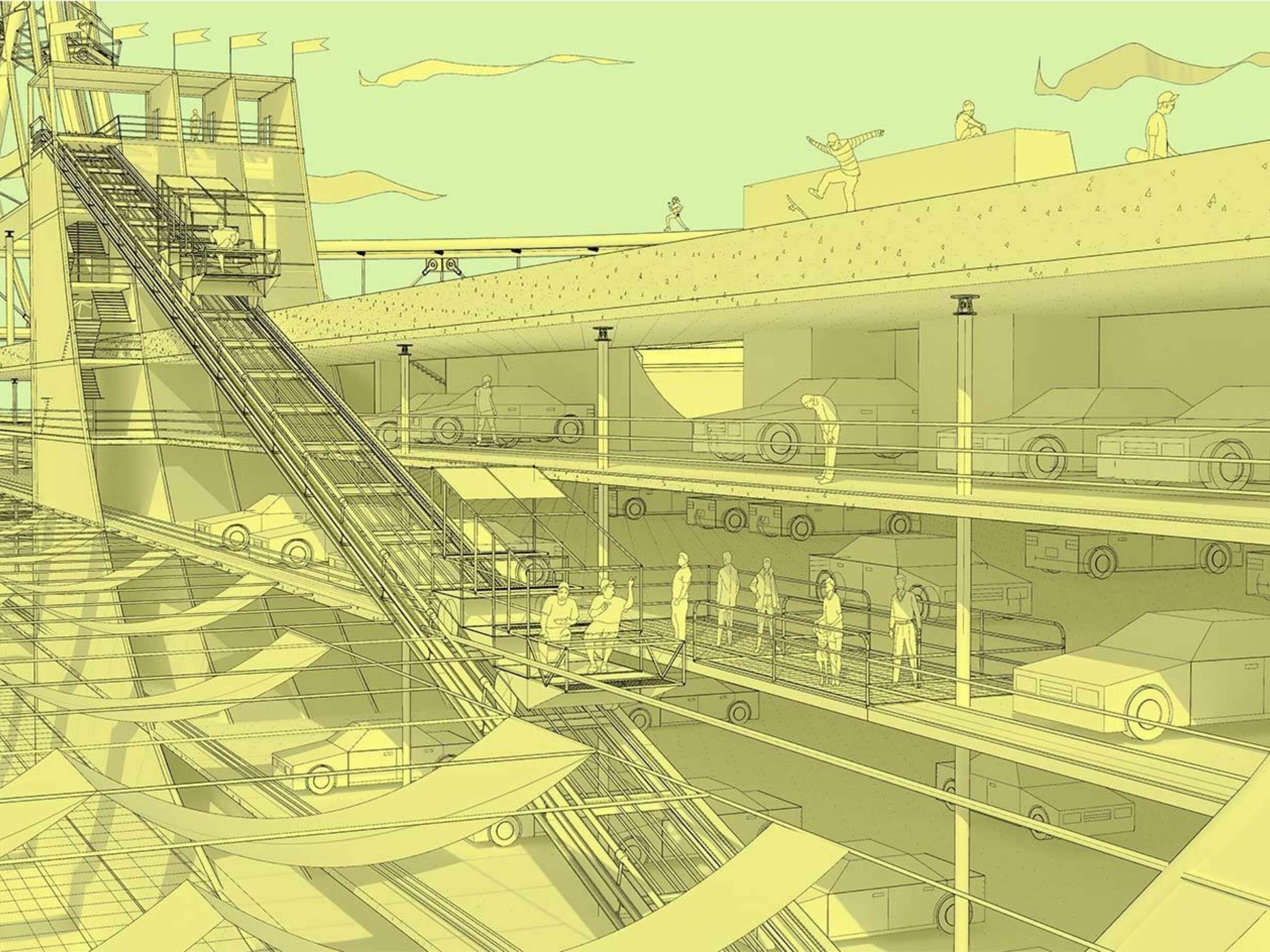

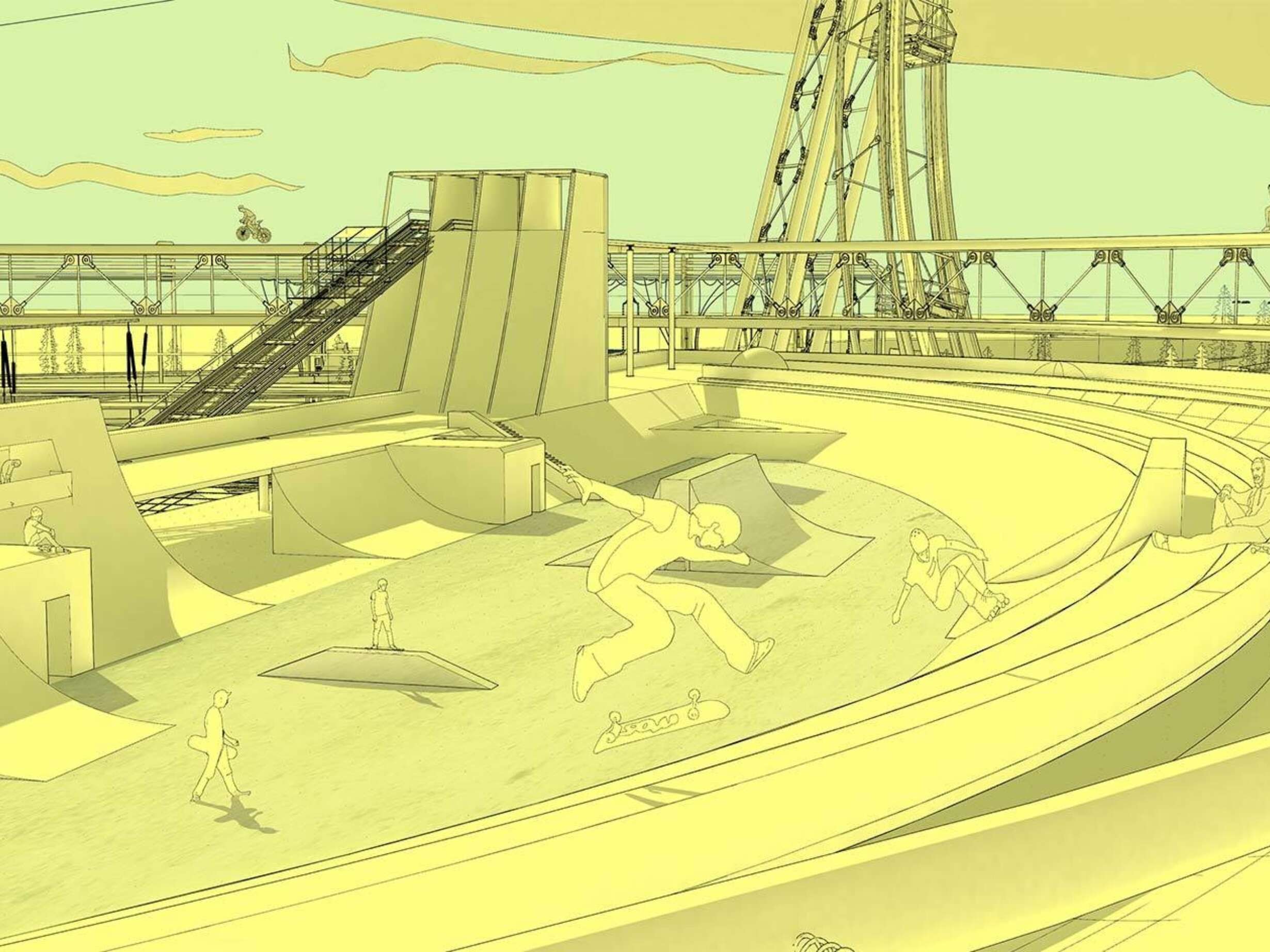

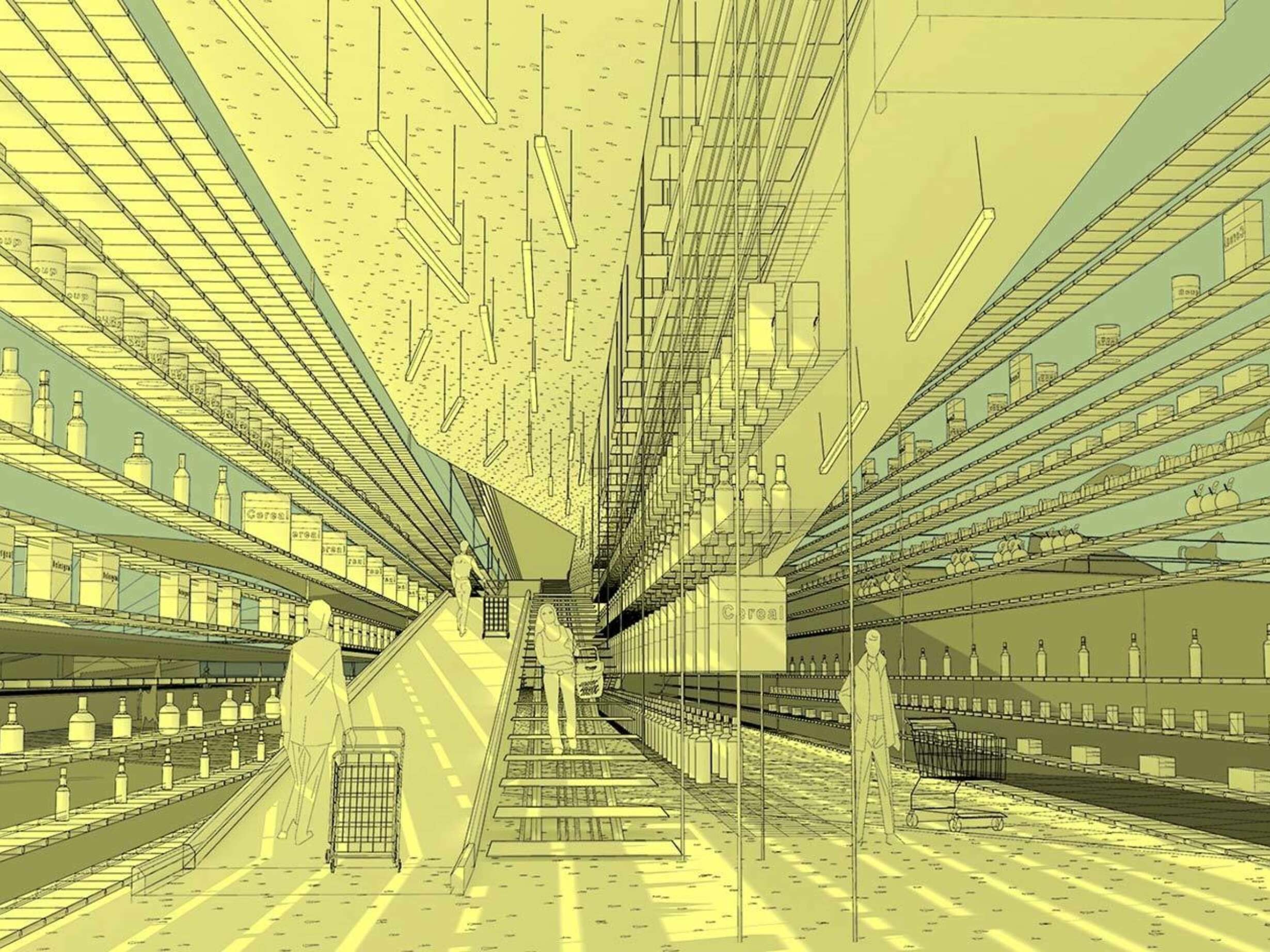

This thesis, seeking an antidote to the authoritarian, researches into a new means of infrastructure, a ludic order which complements the complex layered nature of innate human behaviour, favouring the freedom of uncertain playful movement where control of the stick shift lies with the player. Critically questioning the way in which architectural infrastructure can challenge current authoritarian movement is a step towards a ludic movement. This thesis investigates an architecture that celebrates an aggregation of speeds and play typologies which could perhaps bring to light the playfulness that already exists within. The architecture transforms into an amalgamation of real and imaginary spaces where freedom of playful movement is pursued, limits of road rules are tested and infrastructure is reintroduced as significant conditions of architecture.