Where You From? Bridging the Cross-Cultural Identities of India and Aotearoa

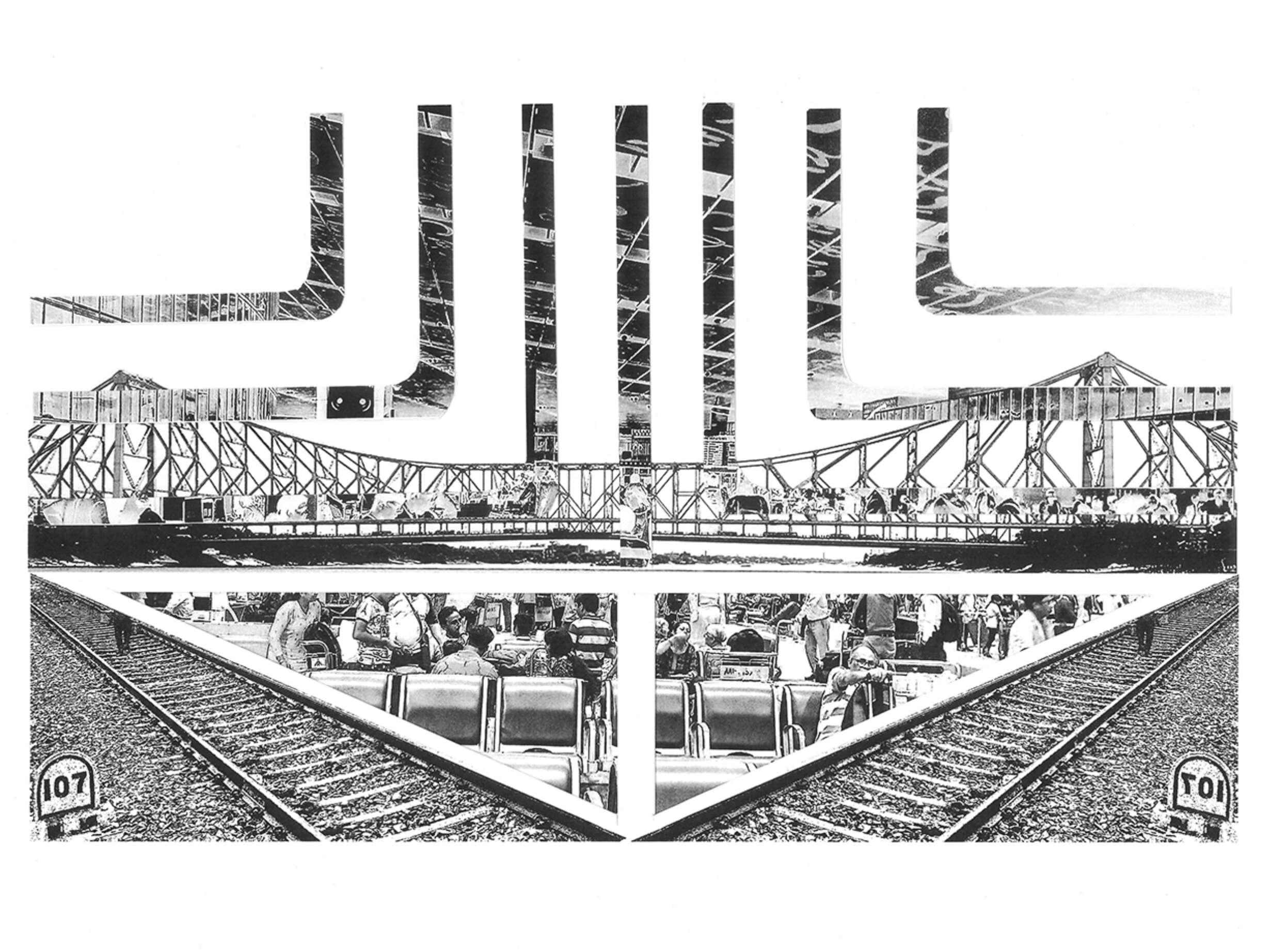

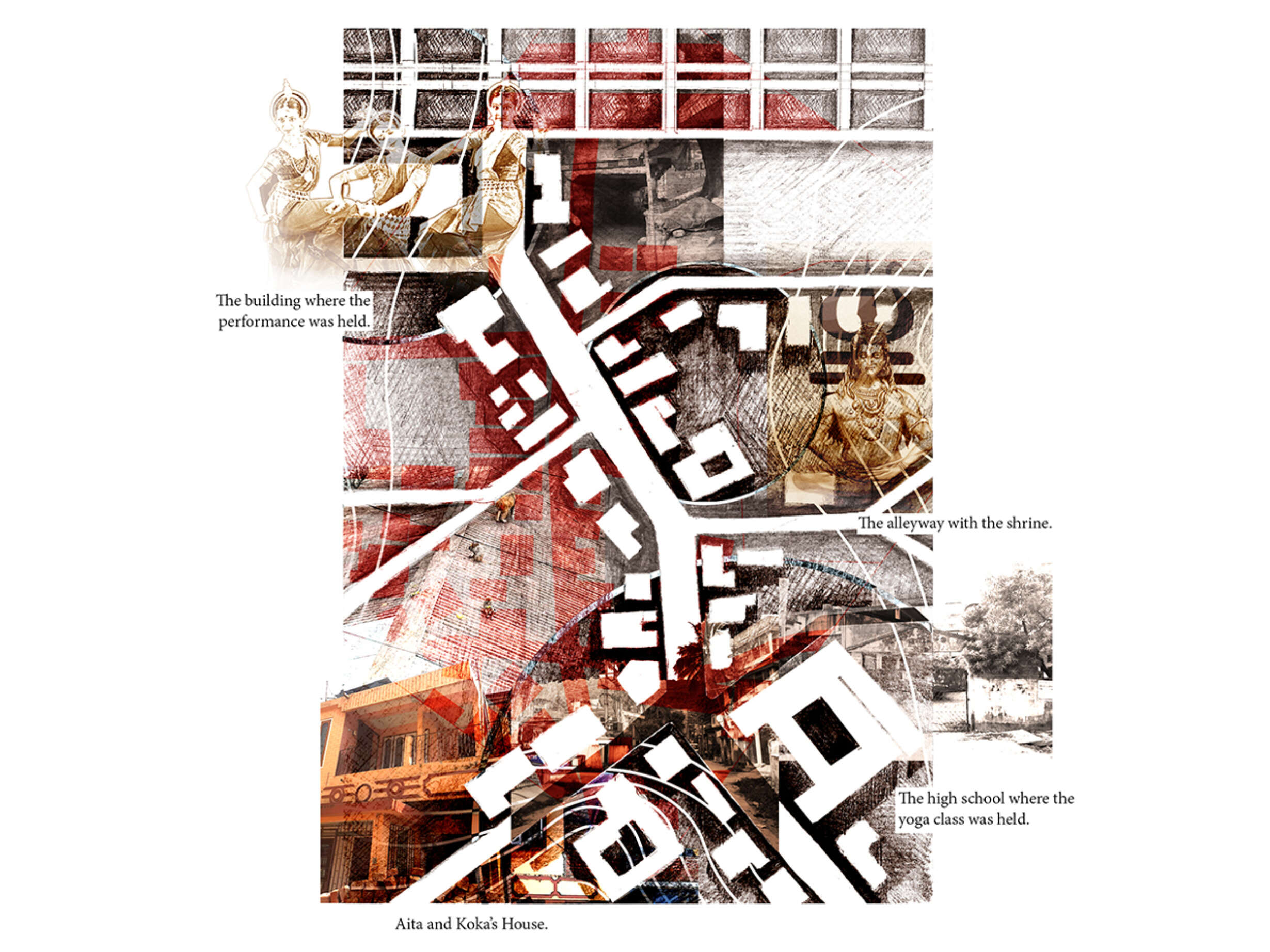

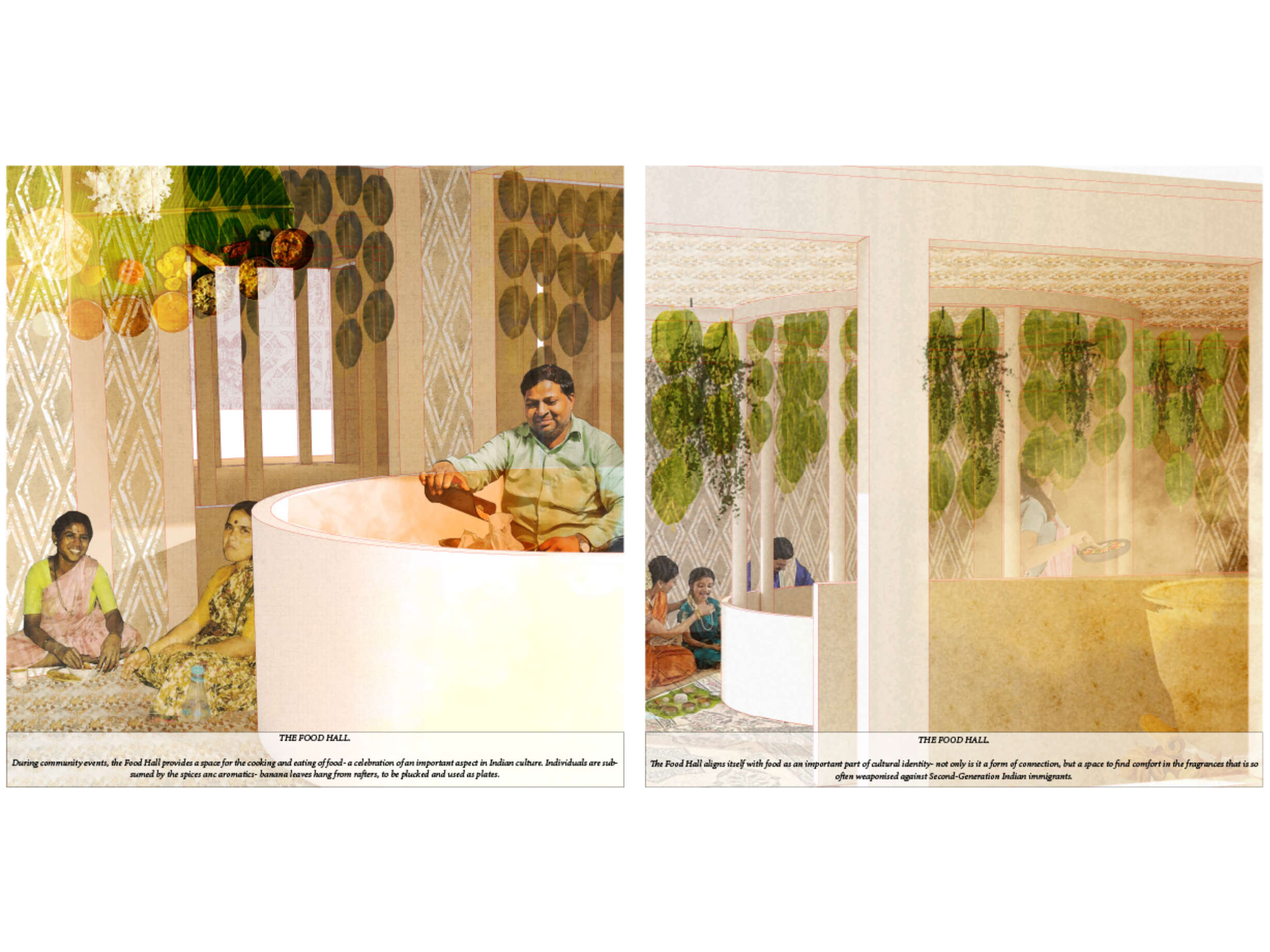

This thesis was born from an introspection of my own identity as a second-generation Indian immigrant living in Aotearoa New Zealand, and the cultural insecurity that comes with living between two worlds. It is within this space of ‘betweenness,’ however, where cultural identity is formed. The design research thus investigates architecture’s capability to connect individuals with their cultural heritage through the conception of a cross-cultural bridging of two interventions in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, and Assam, India.

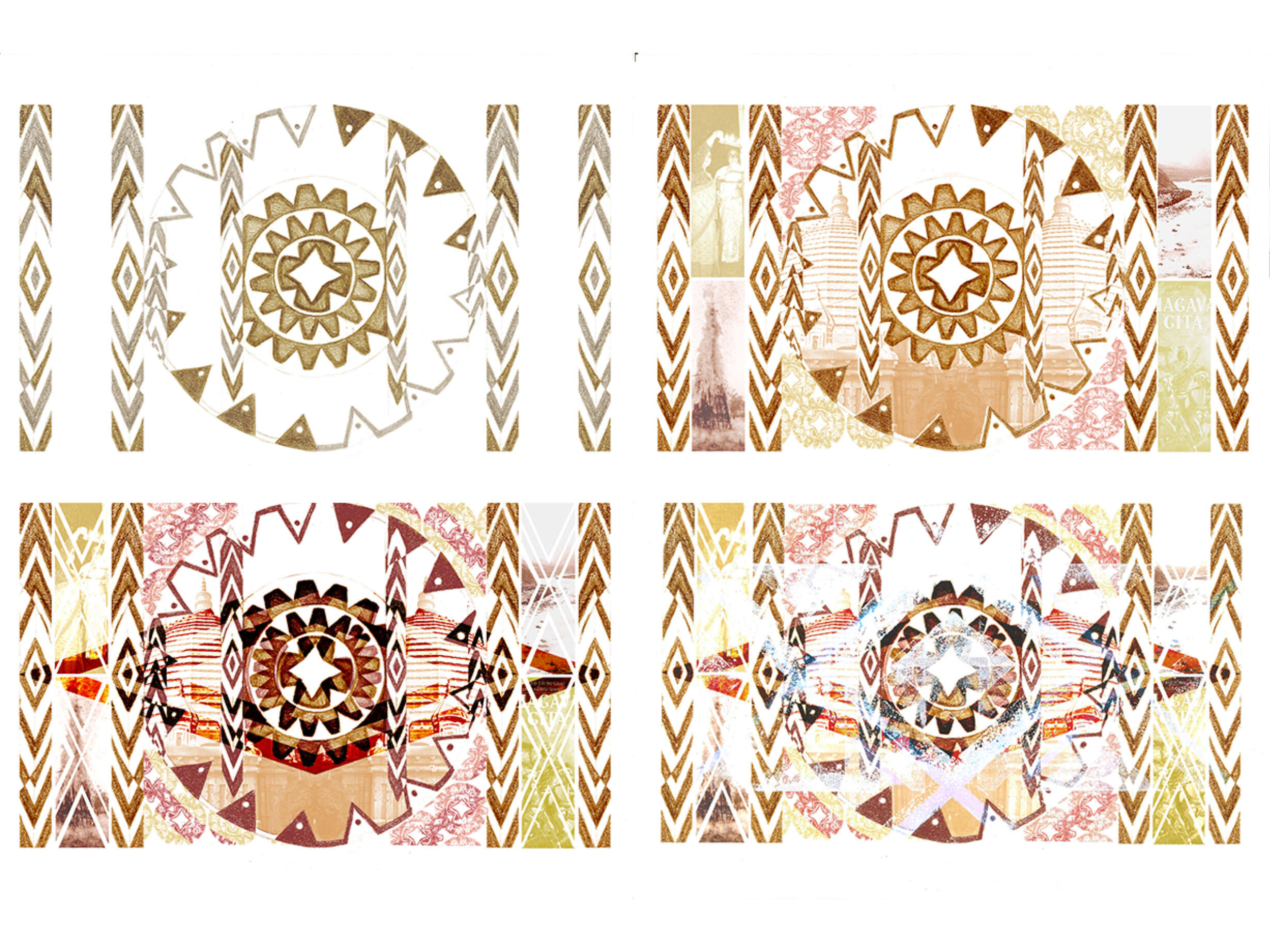

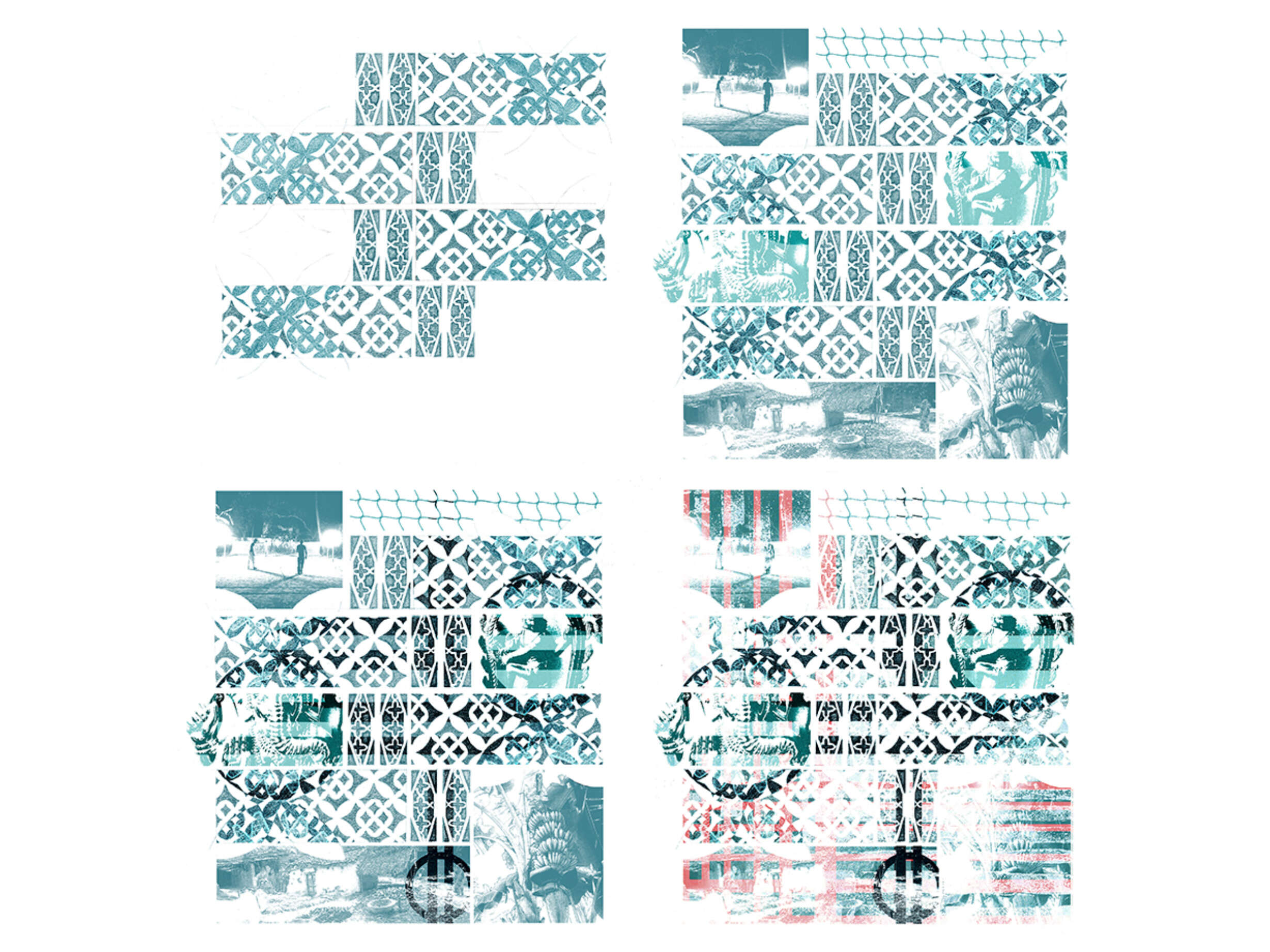

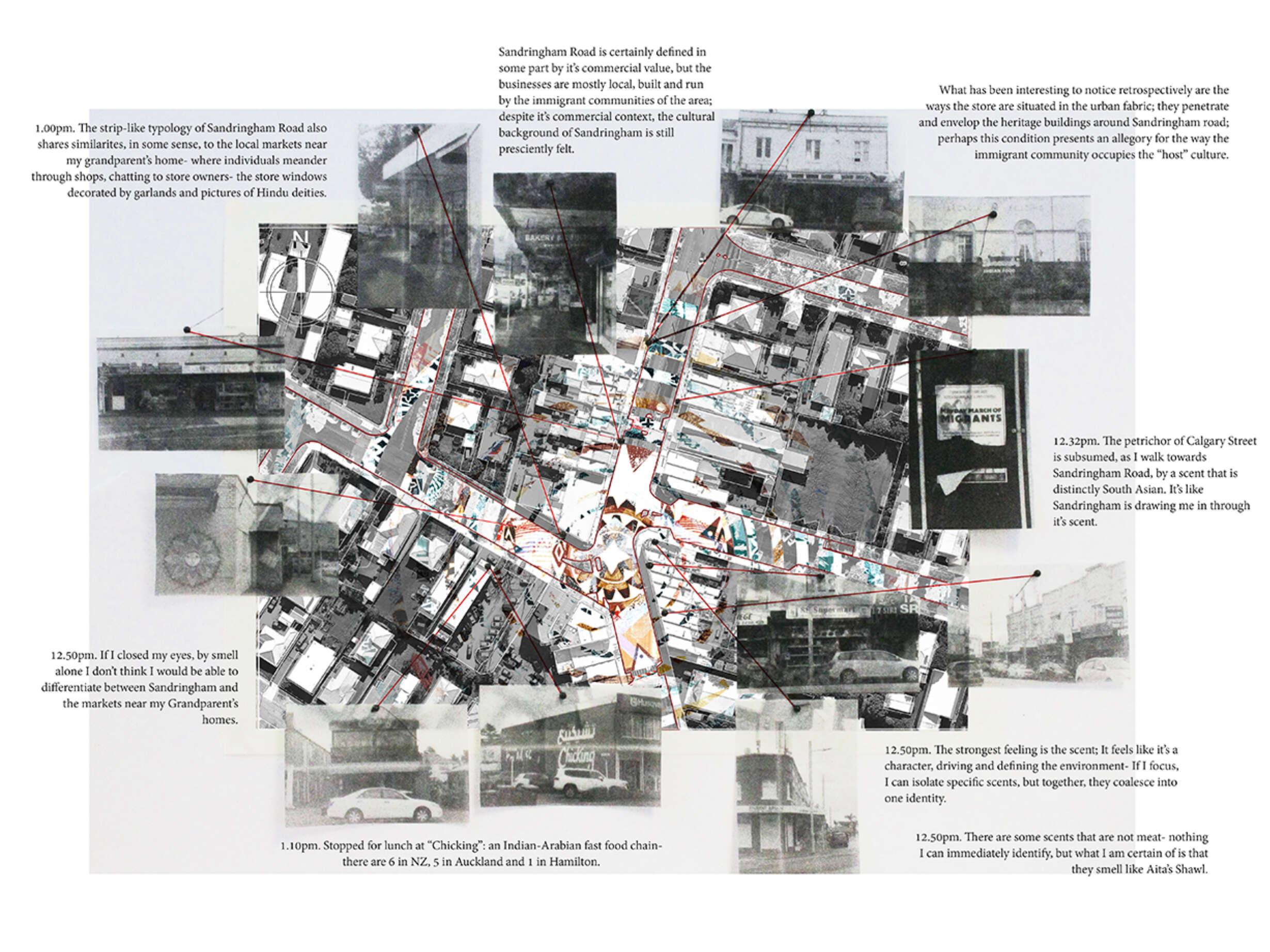

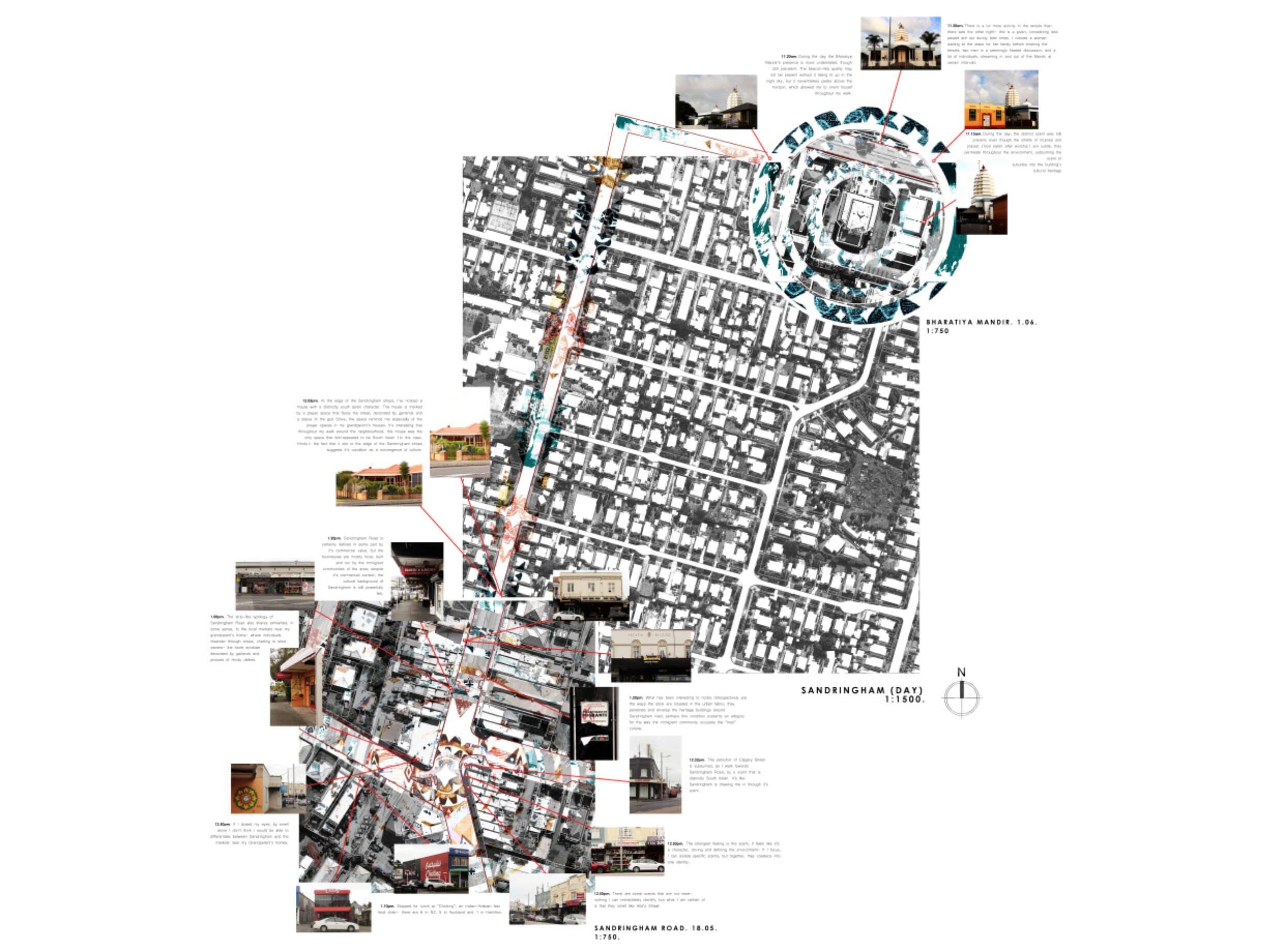

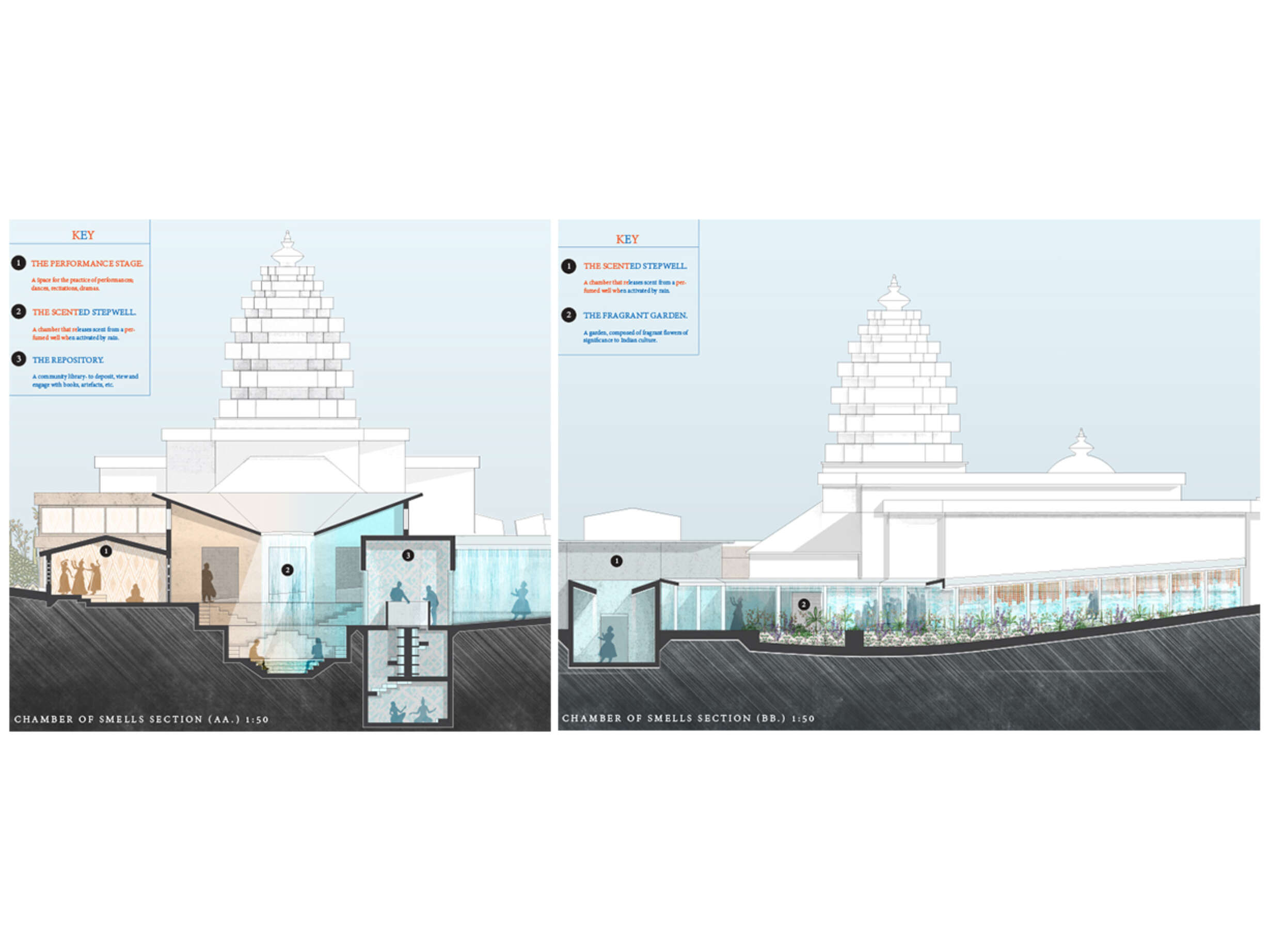

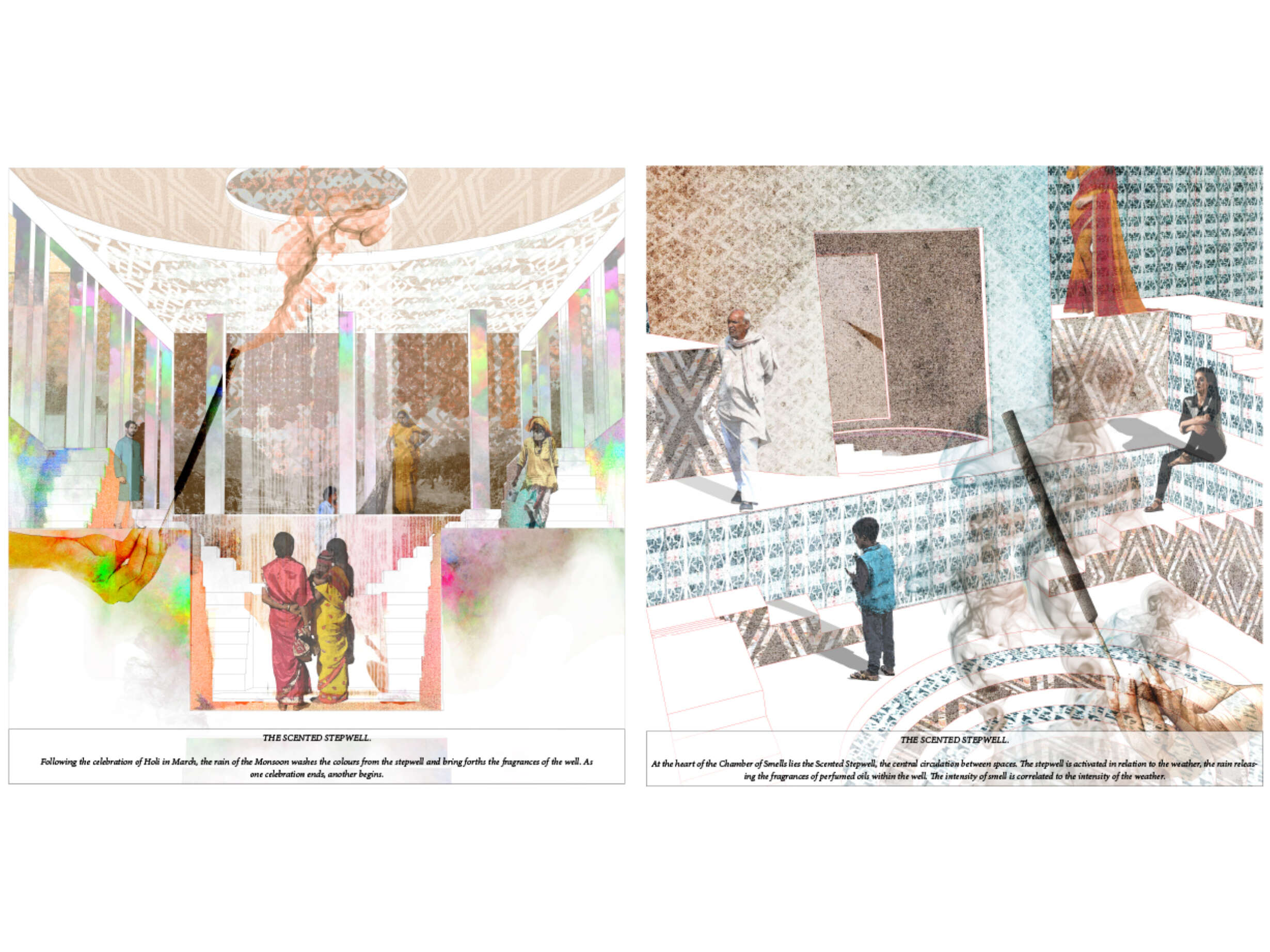

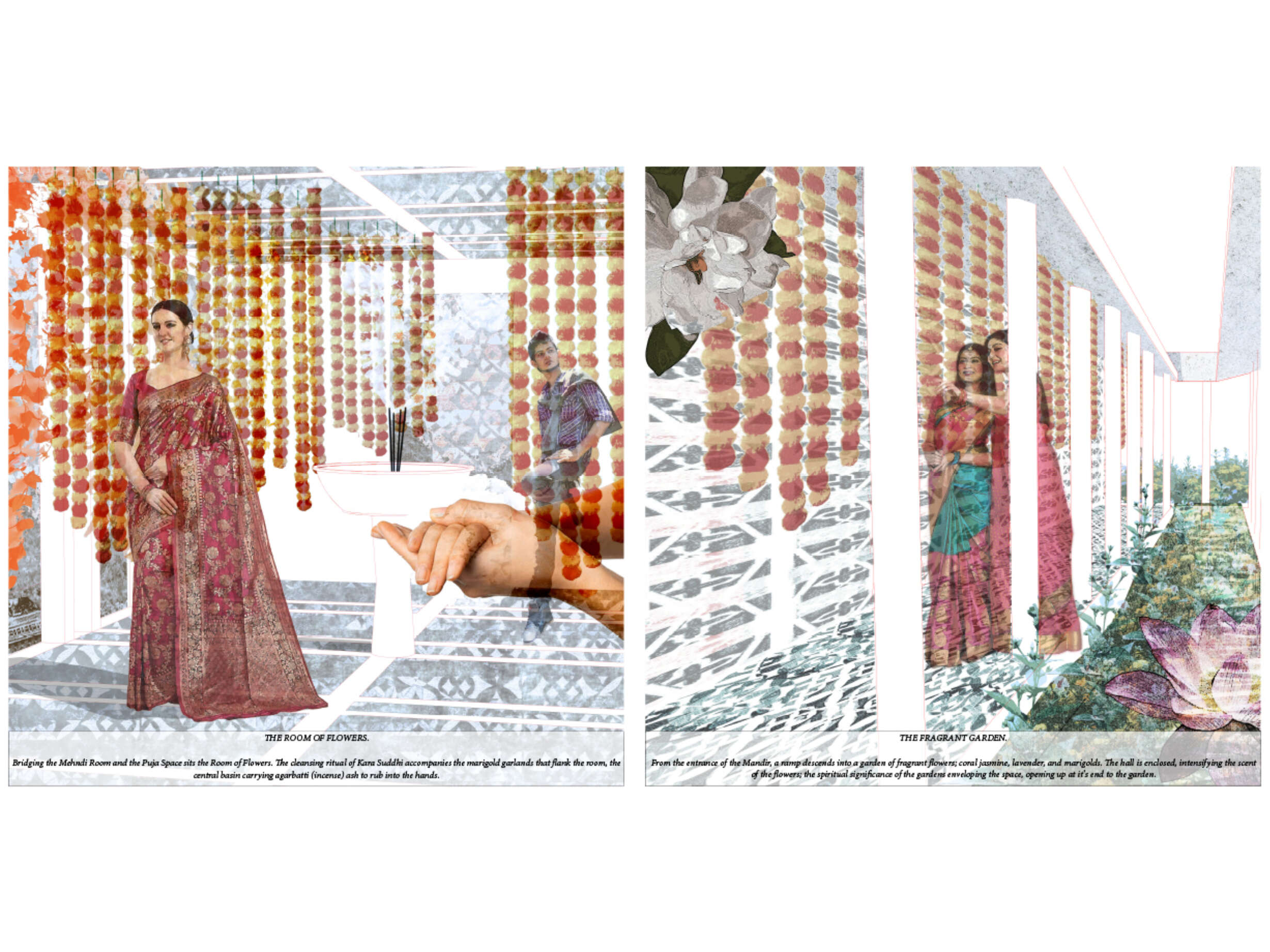

The thesis frames memory as the realm in which our relationship to our cultural heritage crystalises; there is a symbiotic relationship between how we perceive memories as a result of our cultural heritage, and vice versa. This relationship is investigated by examining my own memories as an Indian-New Zealander, informed predominantly by the sense of smell. The olfactory, of the five senses, is most directly connected to memory, and this relationship is explored through a spatial examination of scent as a catalyst to the formation and experiencing of individual memories.

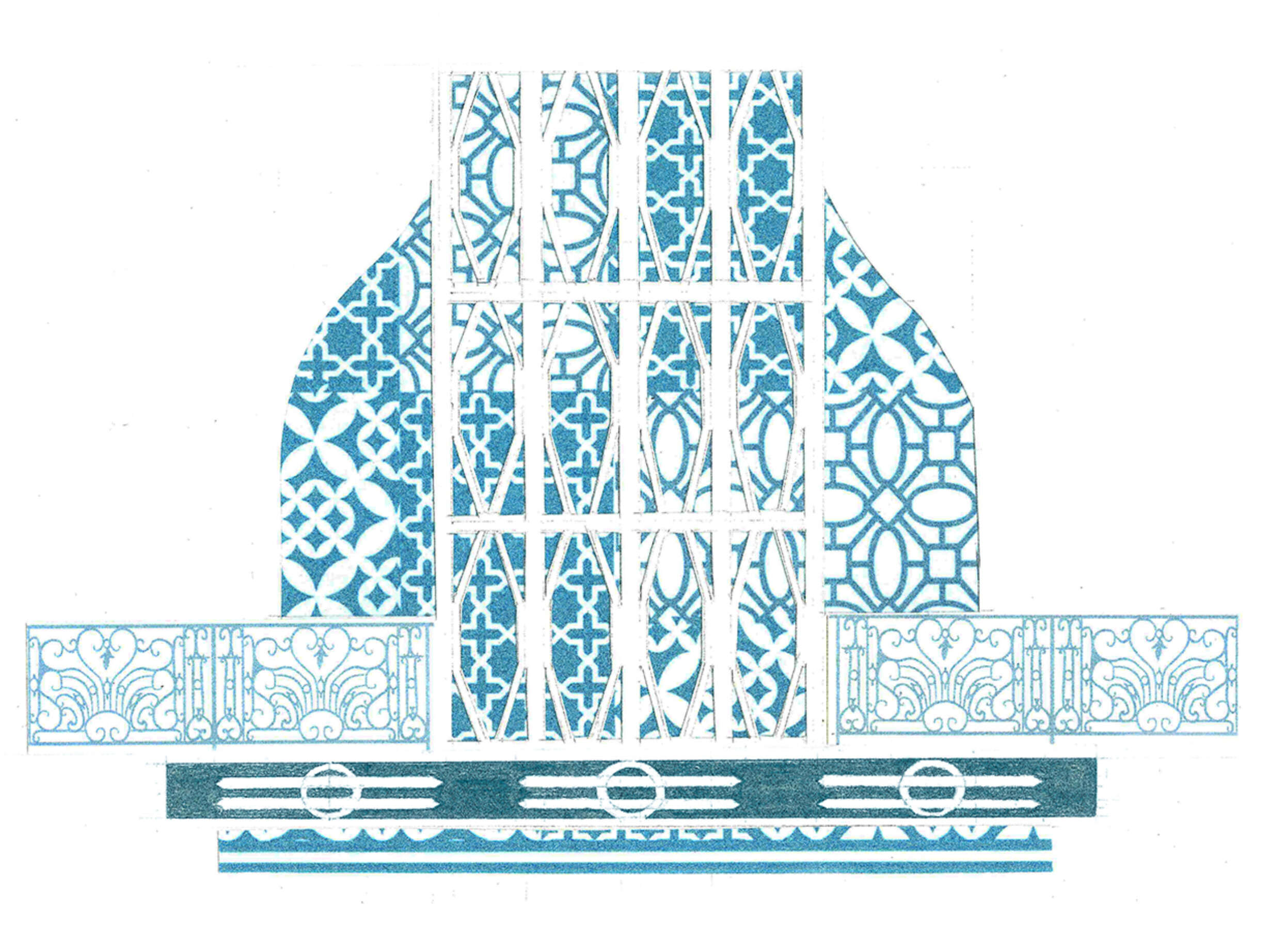

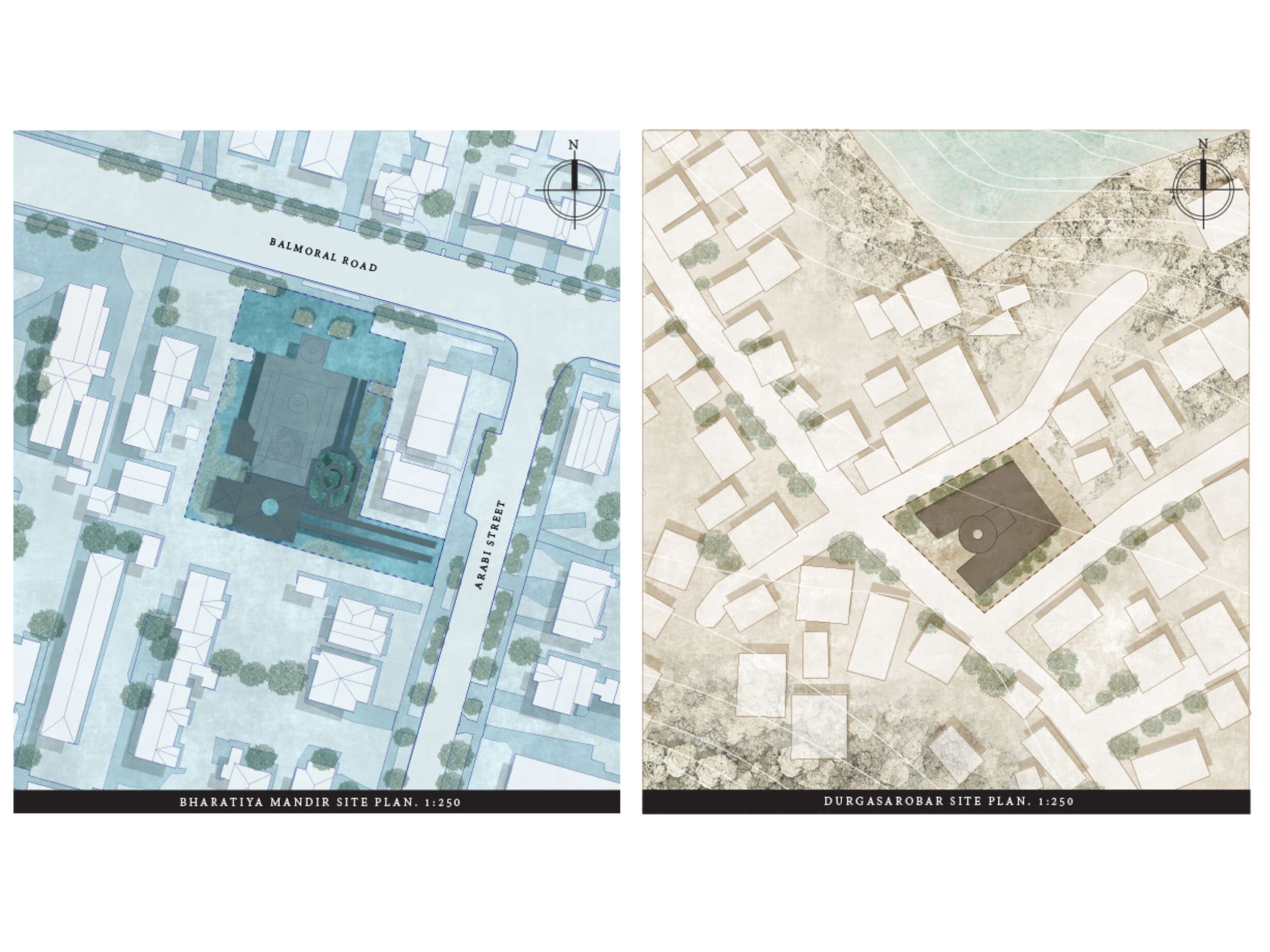

From these investigations, the thesis proposes two architectural interventions in the Bharatiya Mandir temple in Tāmaki Makaurau, and my grandparent’s village, Durgasarobar, in Assam India. The interventions emphasise the olfactory as the driver of design over the ocular sense- the latter being the prioritised sense of the Western world. Between the two sites, a cross-cultural bridge is formed by mirroring two identities.