Architechur Bro

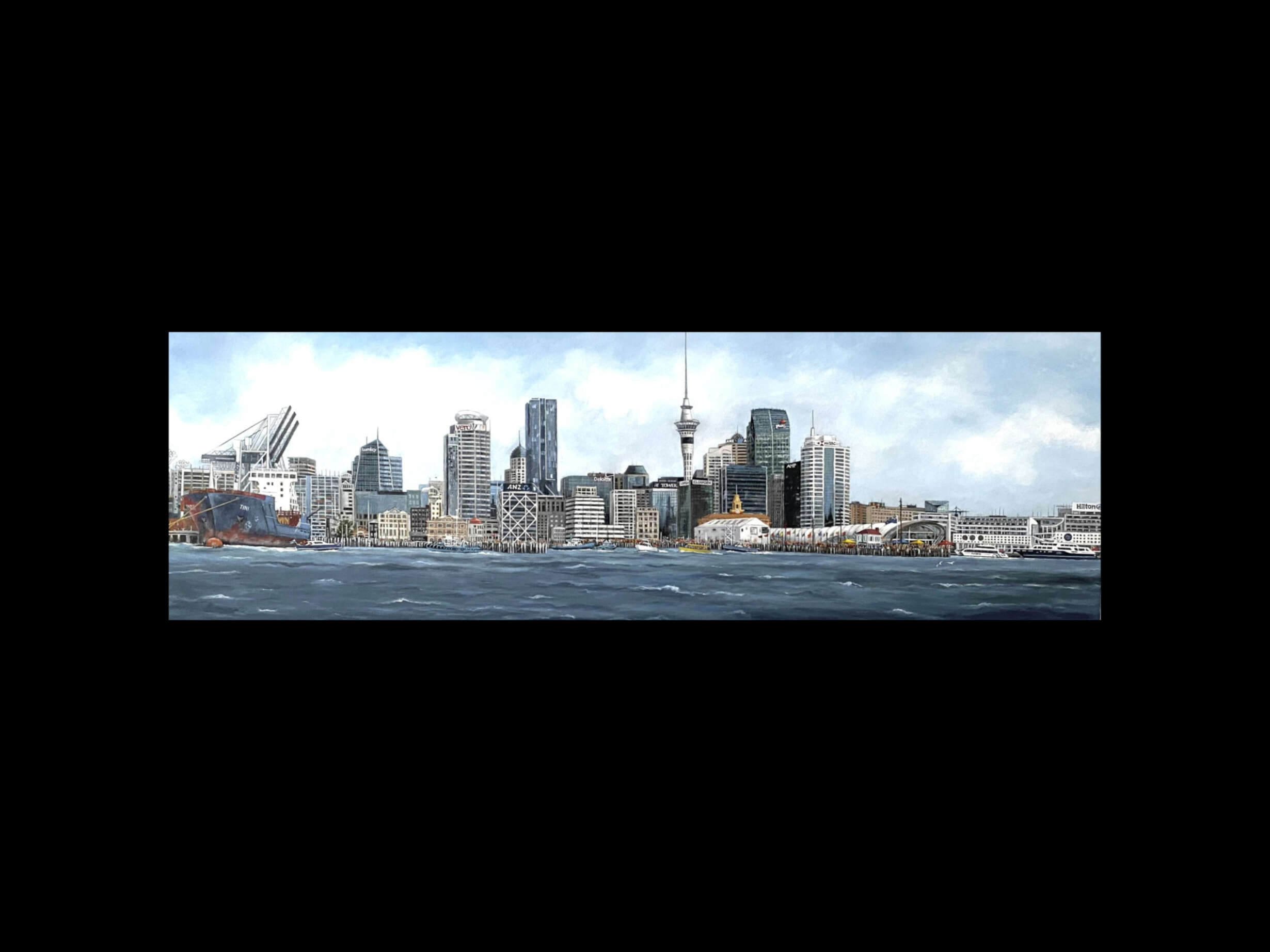

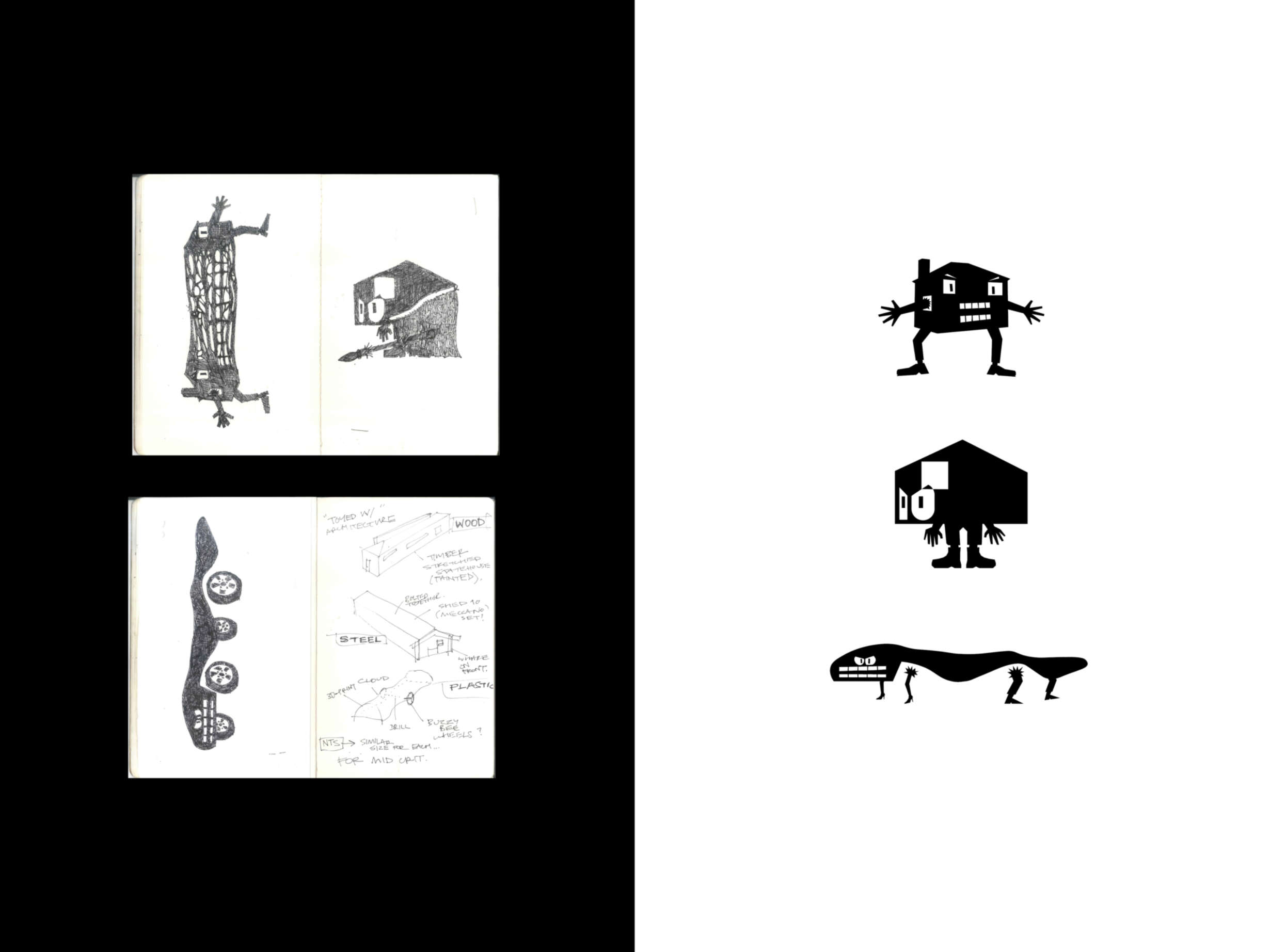

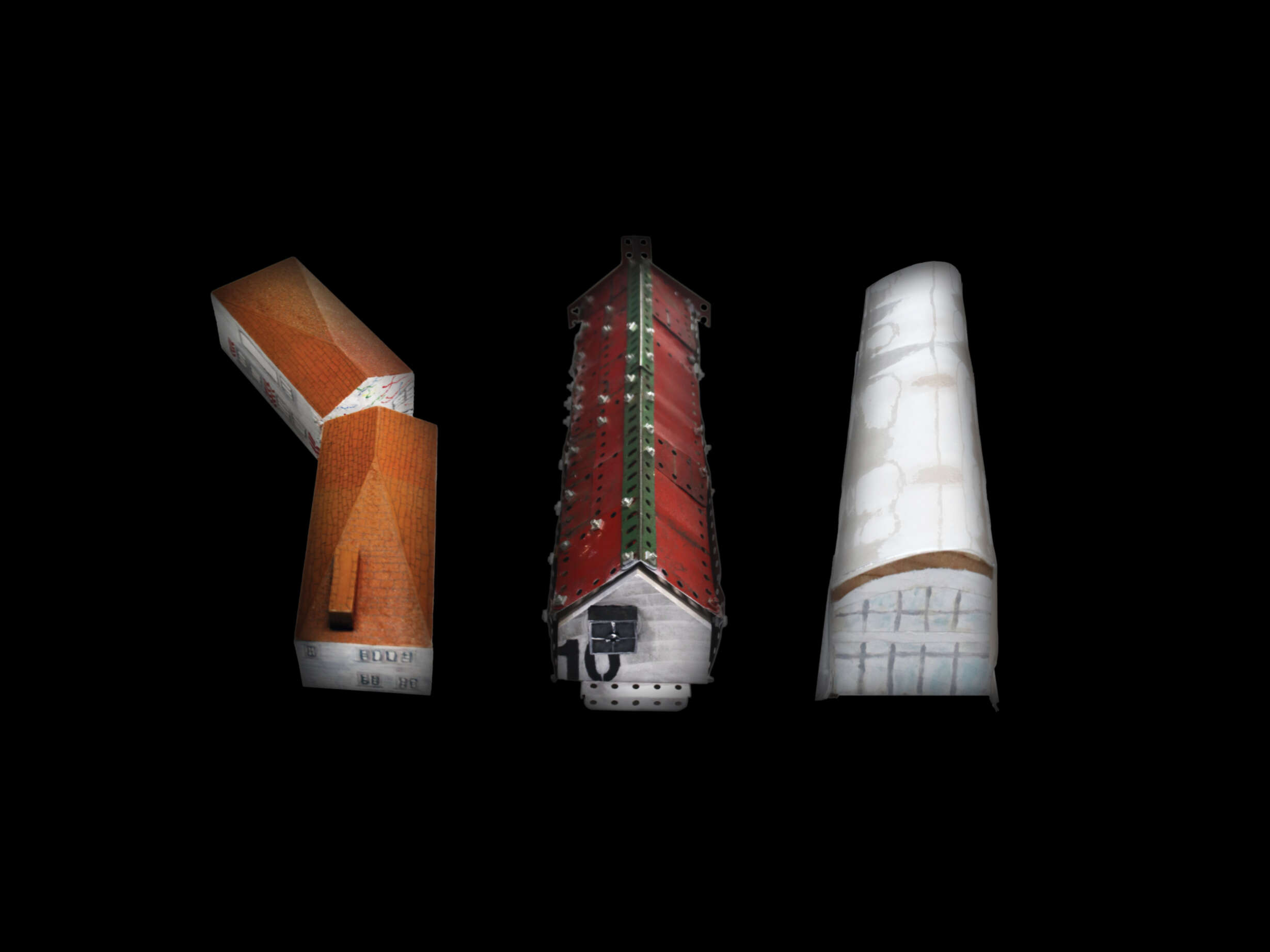

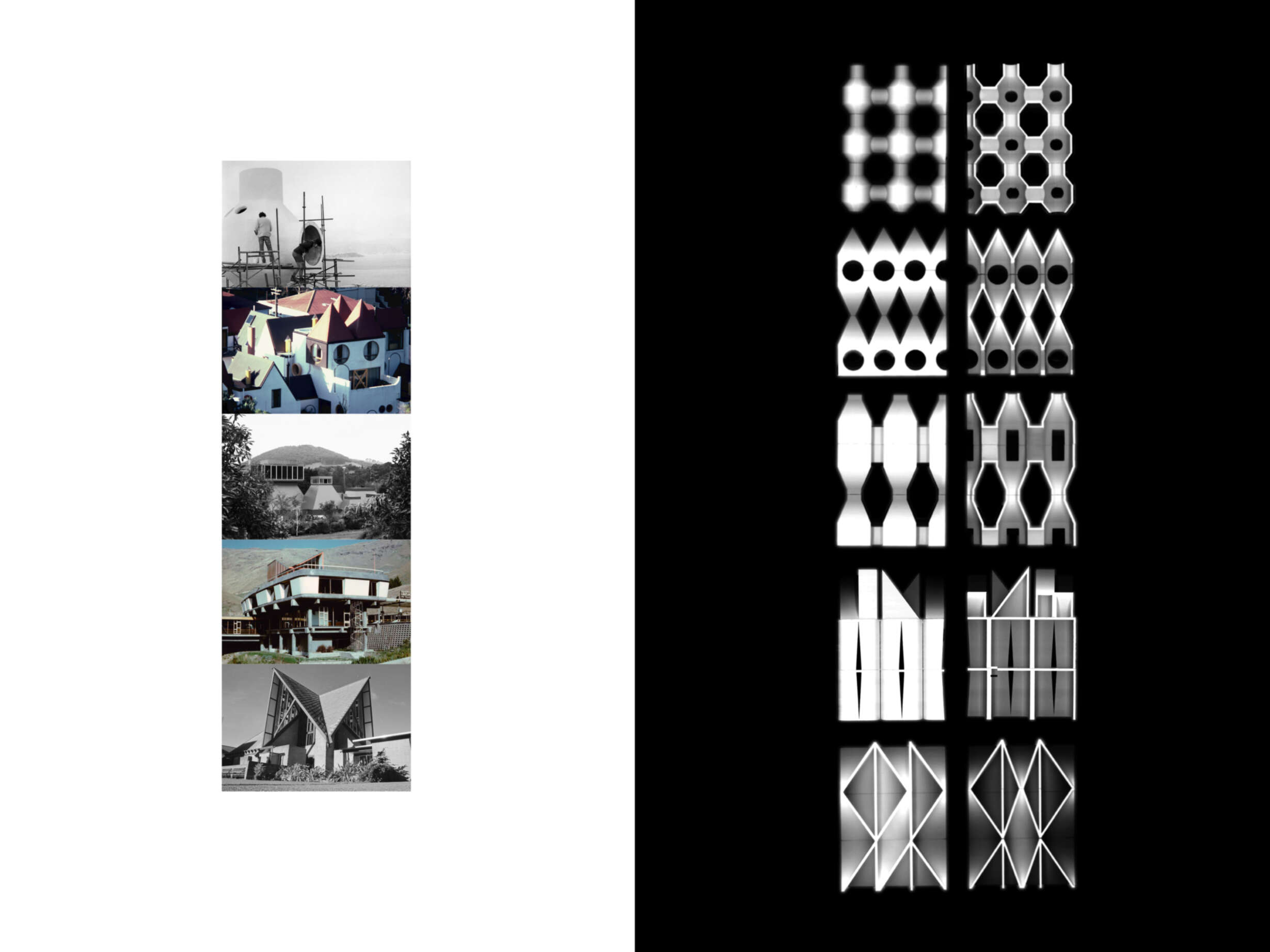

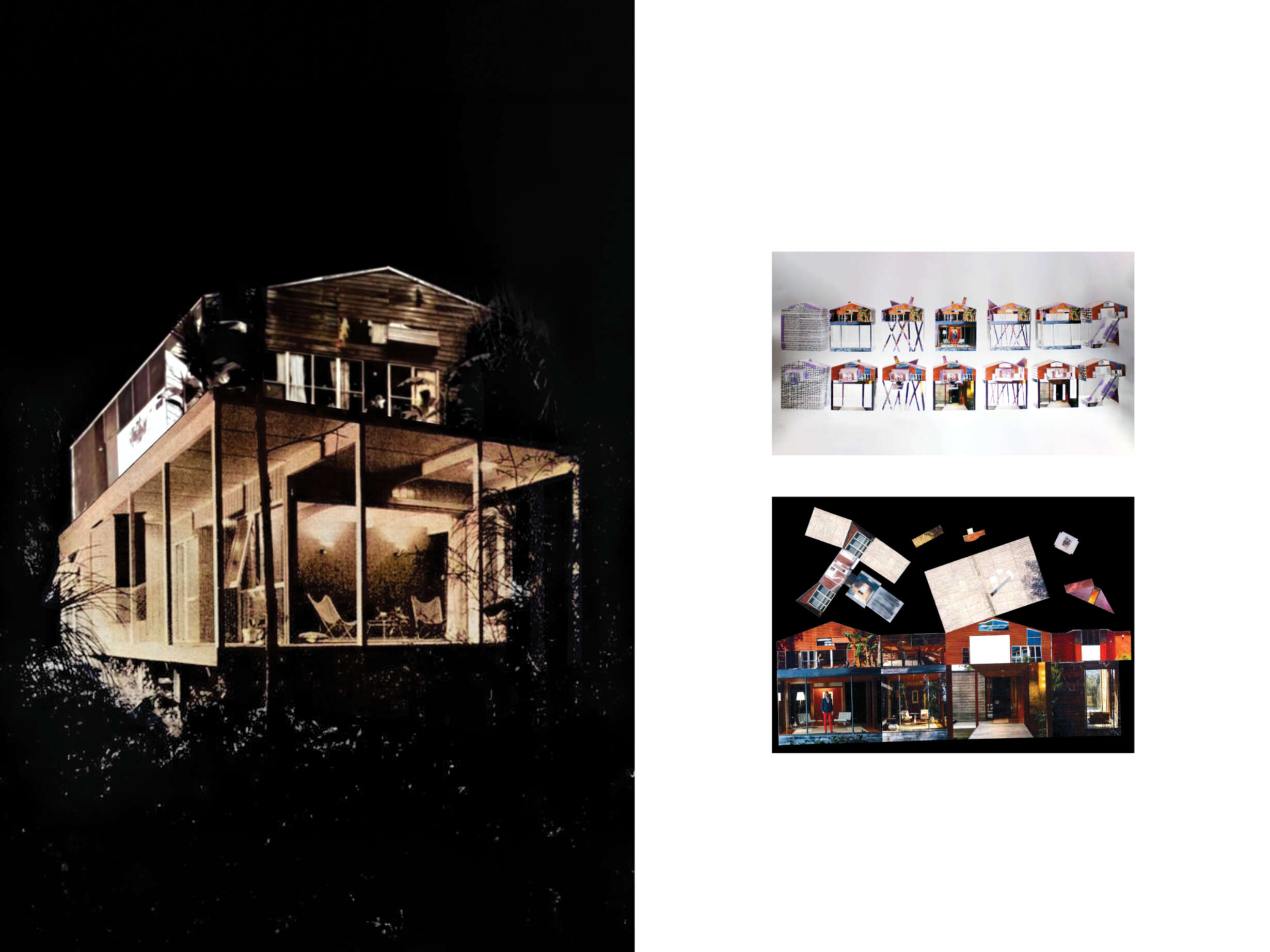

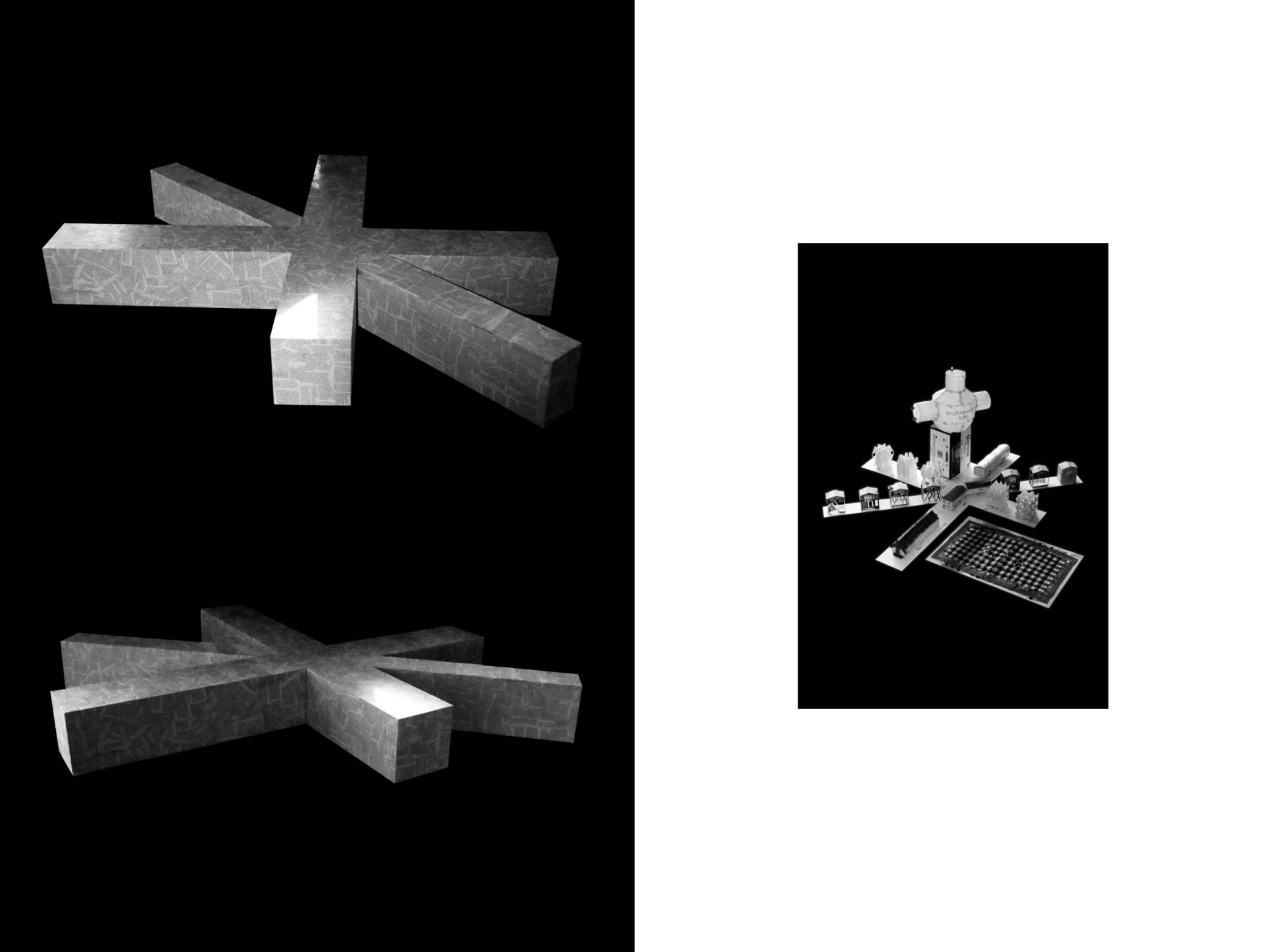

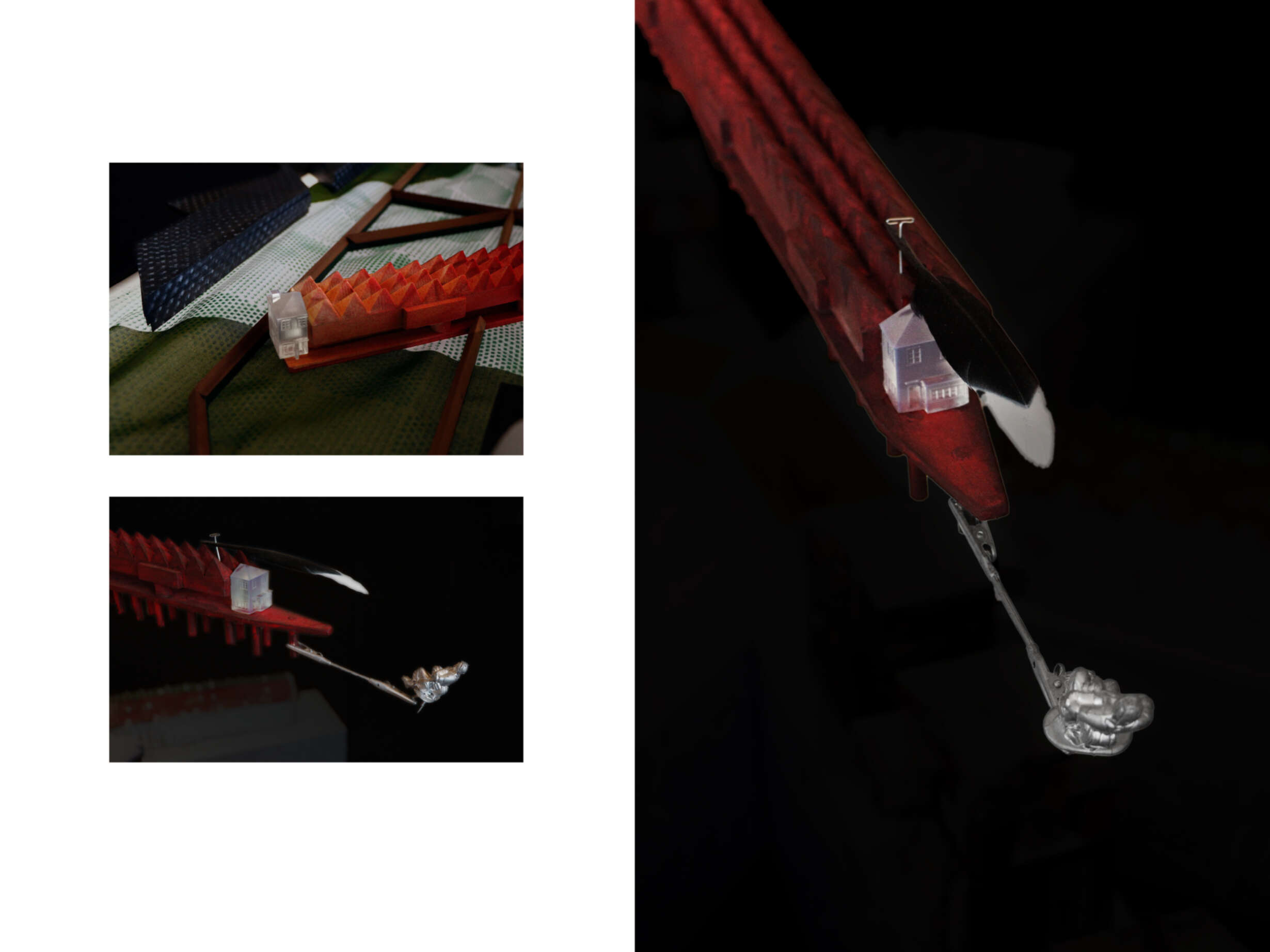

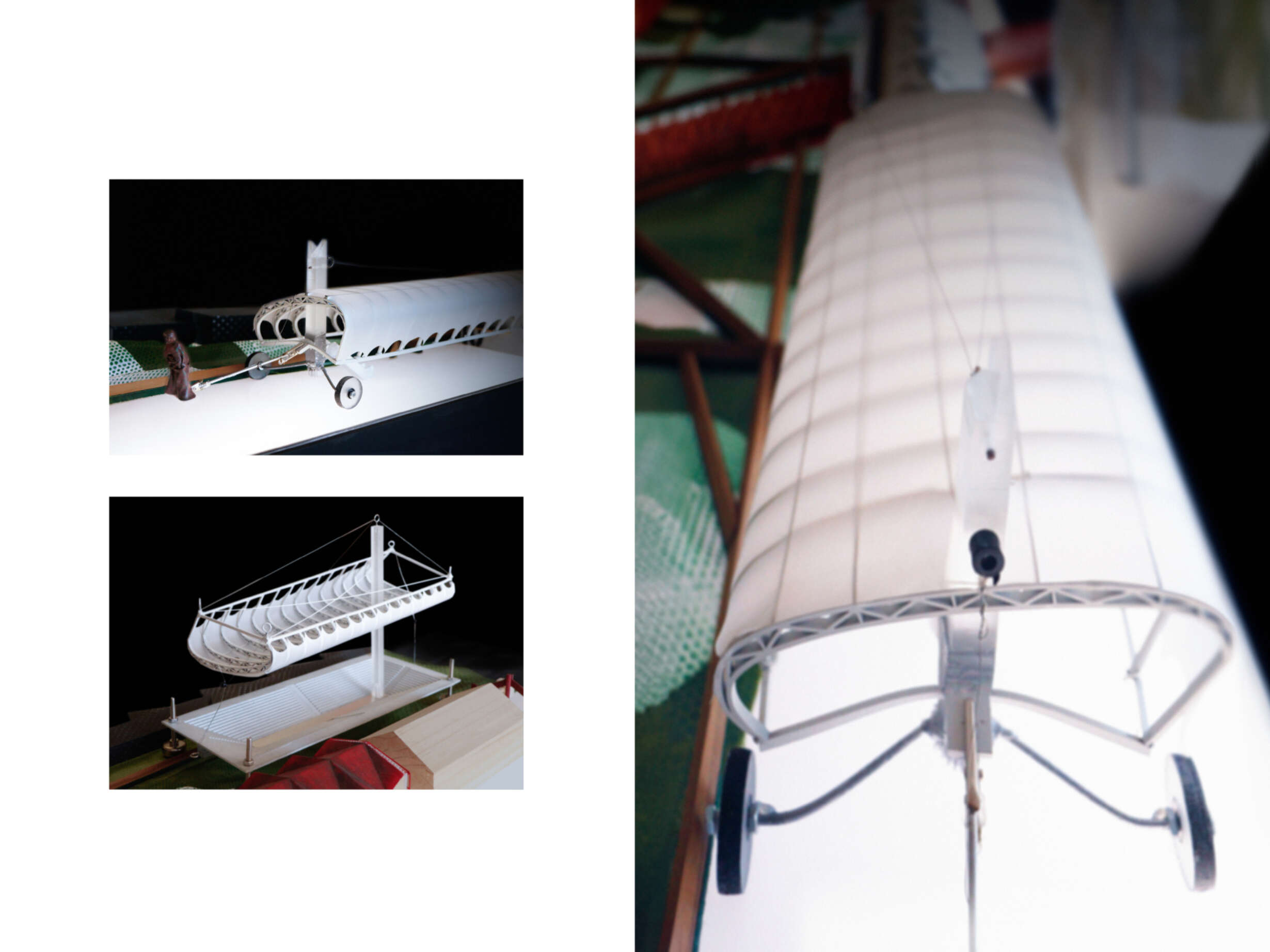

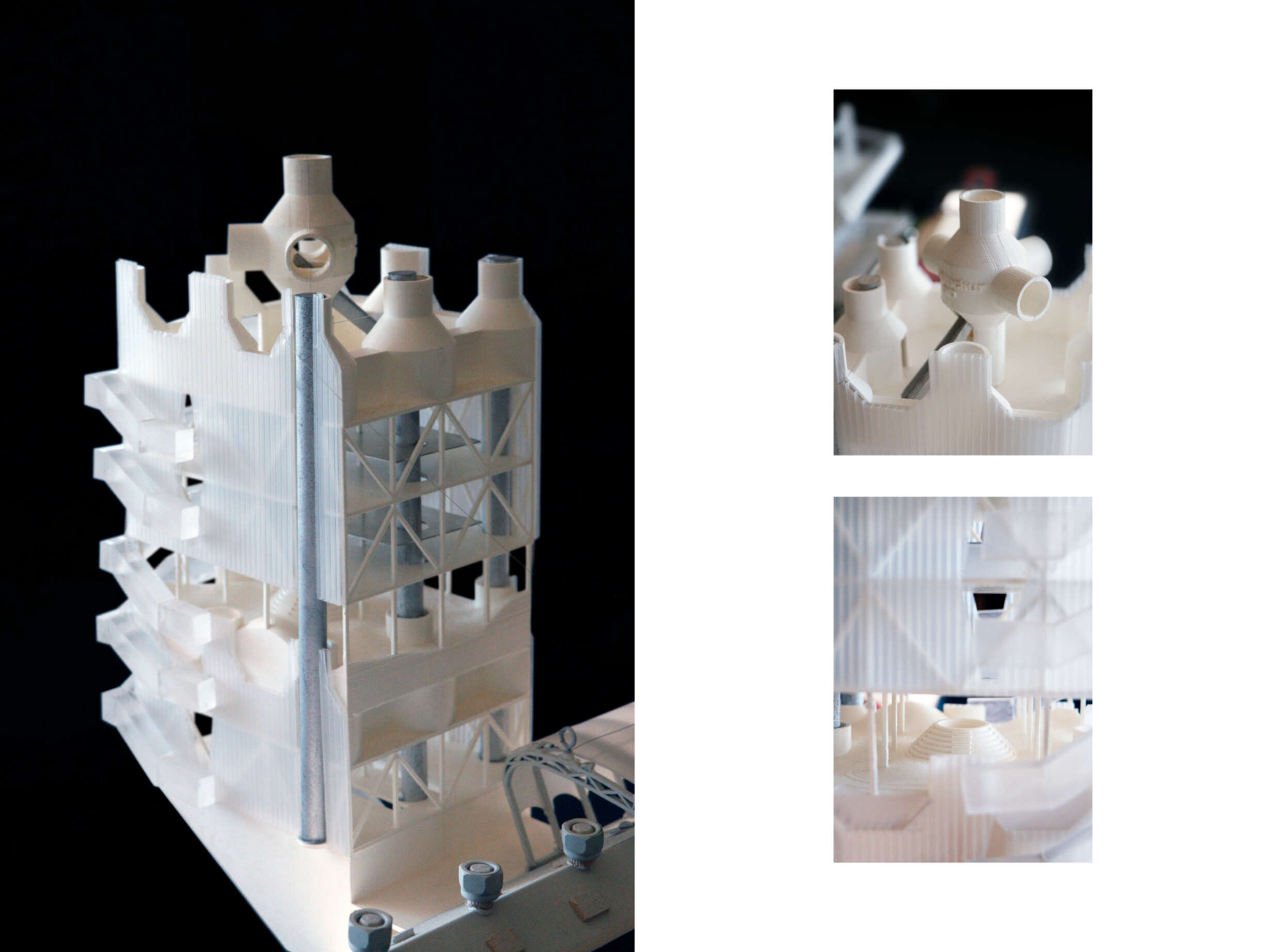

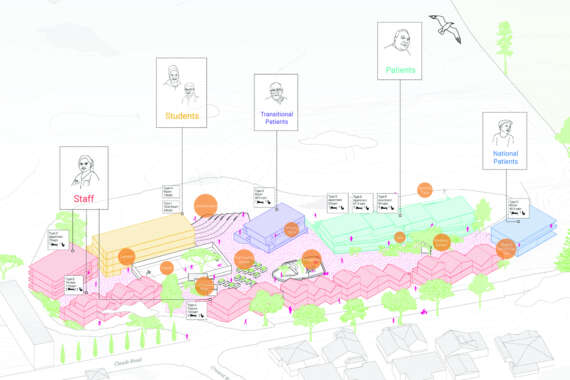

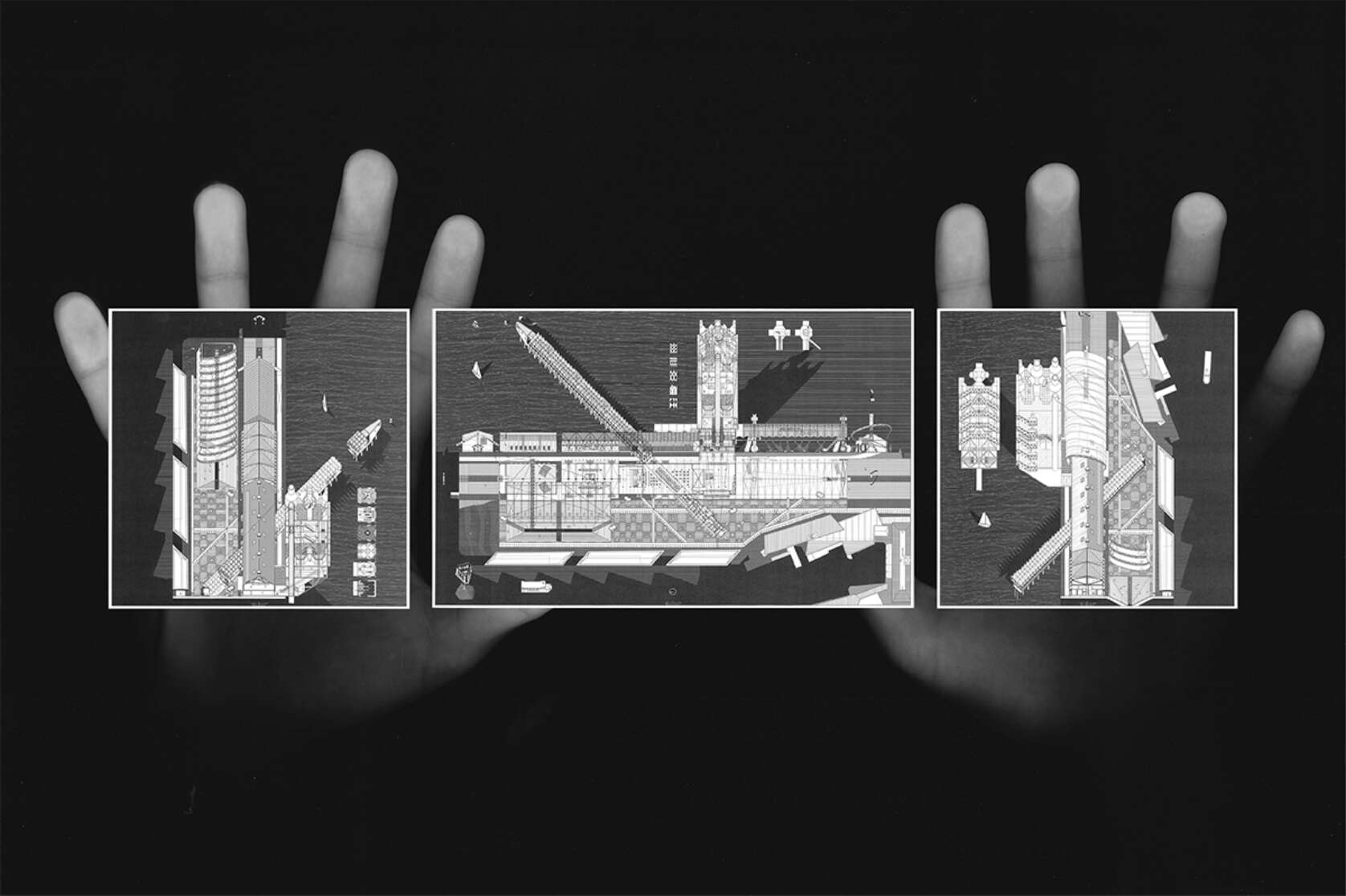

Architechur Bro explores the architect as not merely a designer of buildings, but of worlds, of dreams, or, as key theorist Mark Wigley puts it, an "activist synthesiser of various forms of knowledge and an elegant commentator of the world". The author navigates what it means to make architecture in Aotearoa New Zealand by subverting its architectural history, producing an intertextual product of the South Pacific. Exploiting reality and fiction, Architechur Bro subverts both the literal and metaphorical "ground" from the get-go. Yet, the theoretical "ground" is held up by Wigley, an acclaimed alumnus of Te Pare School of Architecture and Planning. Wigley's somewhat infamous, pre-‘Deconstructivist Architecture' (1988) article, 'Paradise Lost and Found' (1986) diagnoses the country as "a dreamworld uncorrupted by architecture", eliciting "not a certain architecture" but a "certain resistance to architecture". To understand "New Zealand architecture", Wigley goes back to the beginning, back to the "Garden of Eden". Aotearoa is exaggerated to something not 100% Pure; a garden that can be corrupted by a metaphorical snake. In part, the thesis plays the role of this subversive snake. Architechur Bro culminates in a speculative project landing on a contested site, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland's Queens Wharf. A found condition, a thesis testing ground and a failed site haunted by the nickname 'The People's Wharf'. Home to artist Michael Parekowhai's faux state house, the industrial Shed 10 and Jasmax's past-its-used-by "cloud" structure, the wharf acts as a plasticky provocateur — exaggerated to an appendage clipped onto reclaimed land. Later, drawn as a single line and modelled with a translucent table, it may vanish into thin air. But like a table, this project relies on it, as without the wharf, this site-specific scheme would topple over and drown.