“To the Lighthouse” is the name Leith Macfarlane gives to her 2023 thesis project, a title borrowing from the Virginia Woolf (1927) novel of the same name. The latter tells the story of a summer retreat for the Ramsay family in Scottland’s Isle of Skye, a remote place visited over a decade in the early twentieth century and that witnesses a mix of joys and tragedies for the family. The lighthouse itself in Woolf’s novel is a kind of ever-present draw that the family keeps putting off visiting, but which stands in as an object of shared desire and potential fulfilment.

Lighthouses of course are utilitarian, yet dreamy architectures, standing on coastal edges radiating caution to nighttime mariners, but also suggesting a certain solace: land is here awaiting return and the completion of journeys. These complex associations fittingly organise Leith’s difficult topic of investigation: family violence. The project compliments an earlier body of research Leith commenced while studying for her law degree. It seeks to answer, in a different disciplinary context, the question of how to address the runaway violence unfolding in our homes. Of course, there is no simple answer to this, given how complexly it is embedded socially and historically in our dwelling patterns and in our gender patterning.

Part 1 – Dark Machines

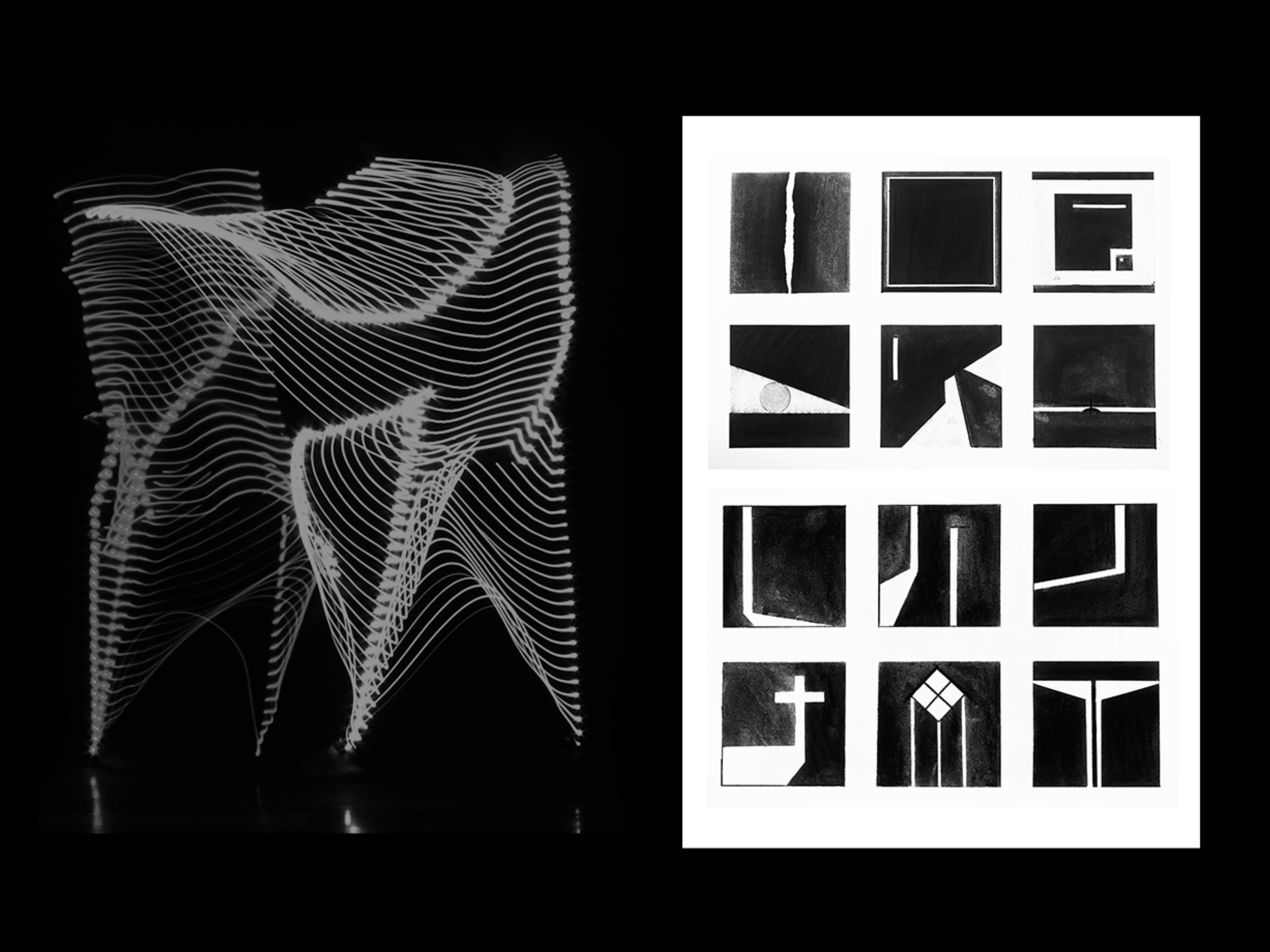

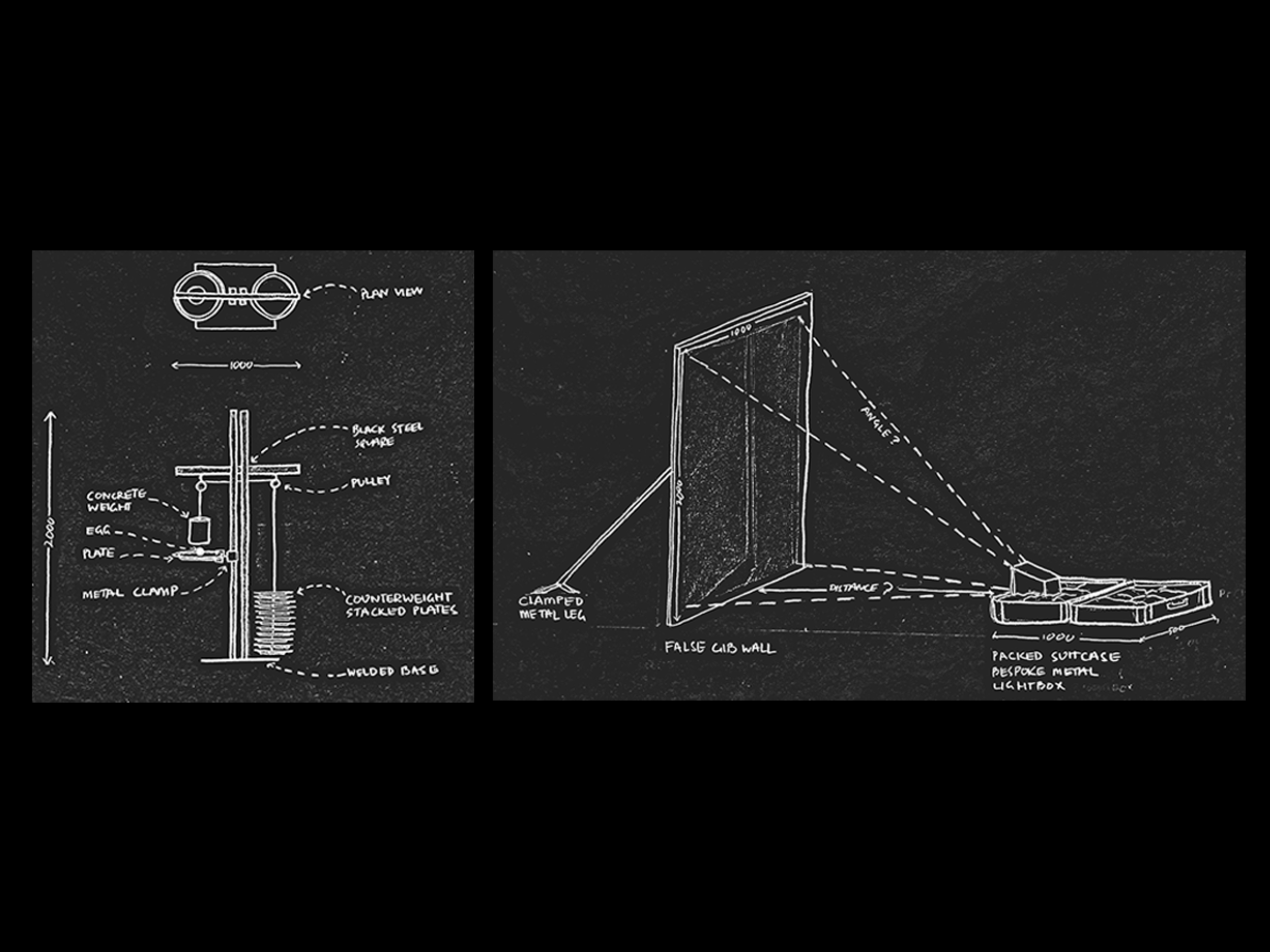

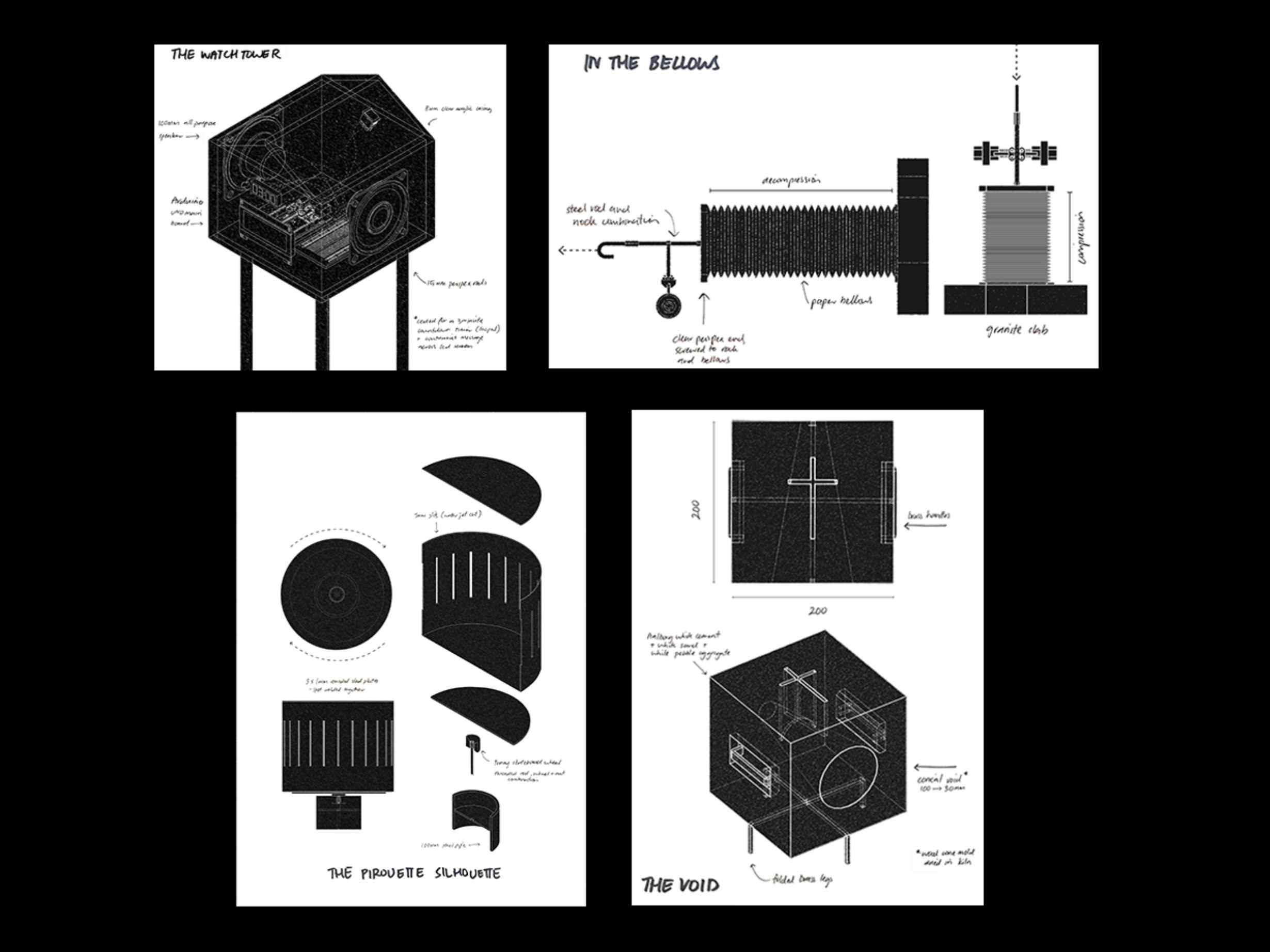

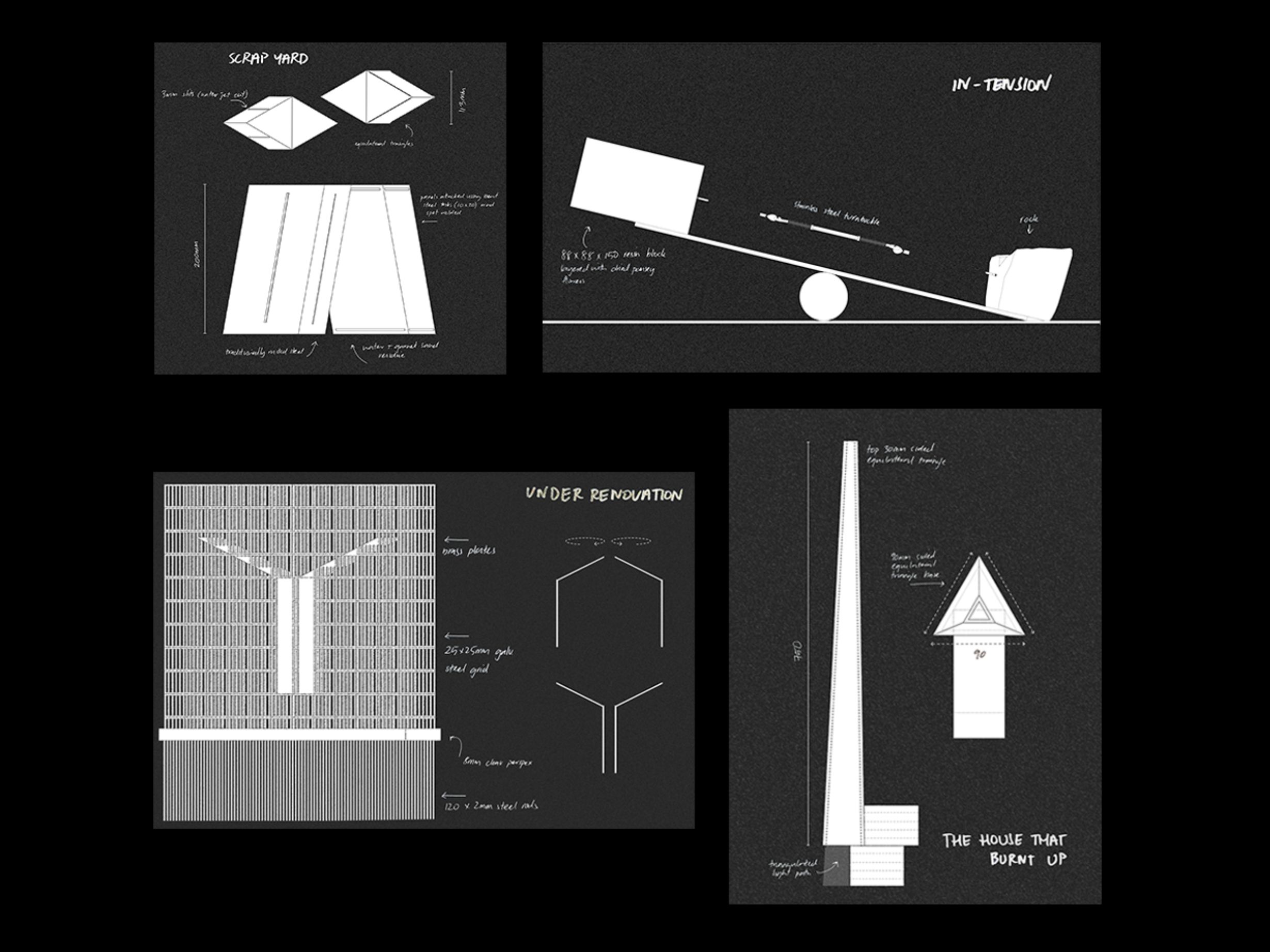

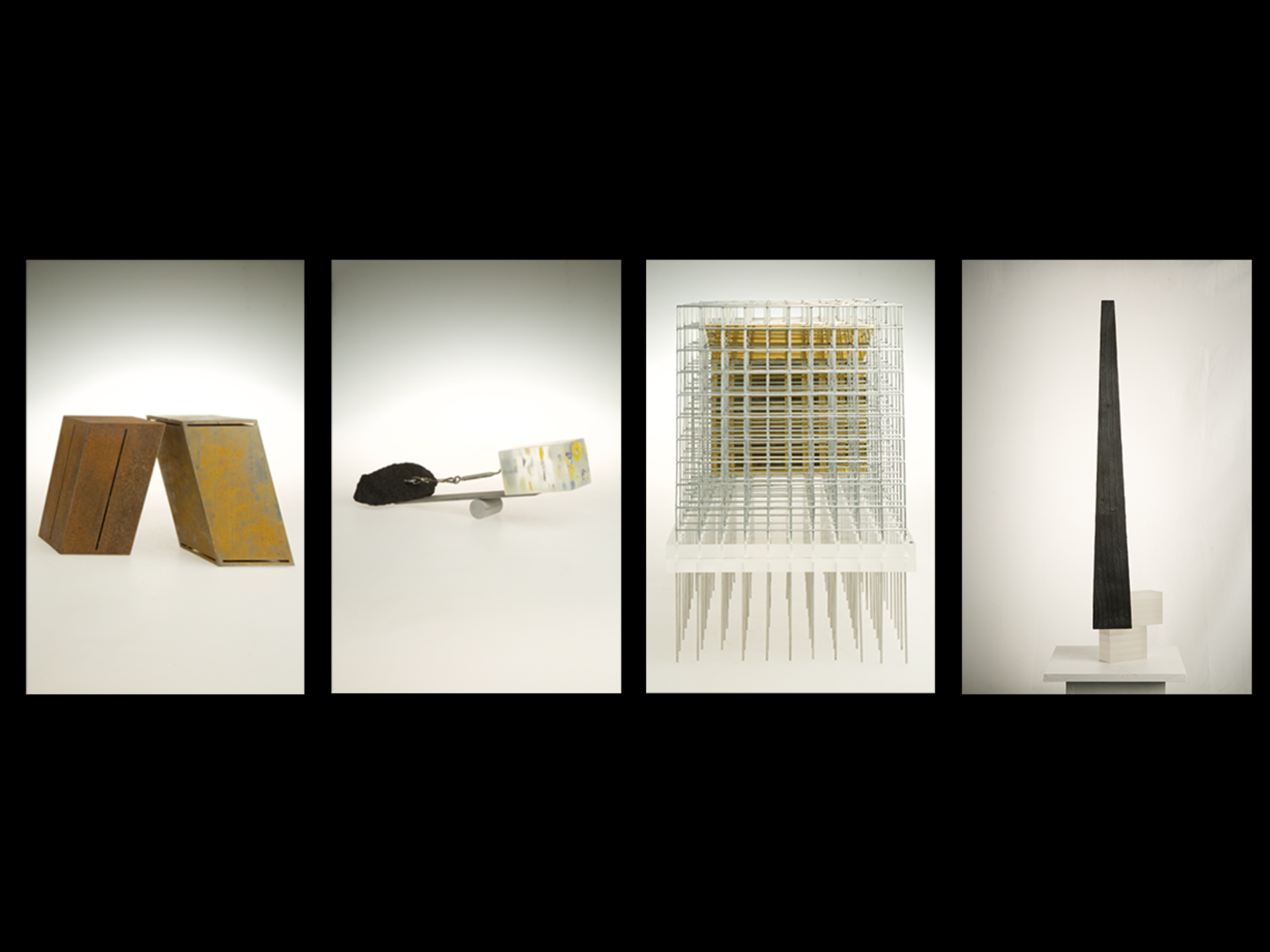

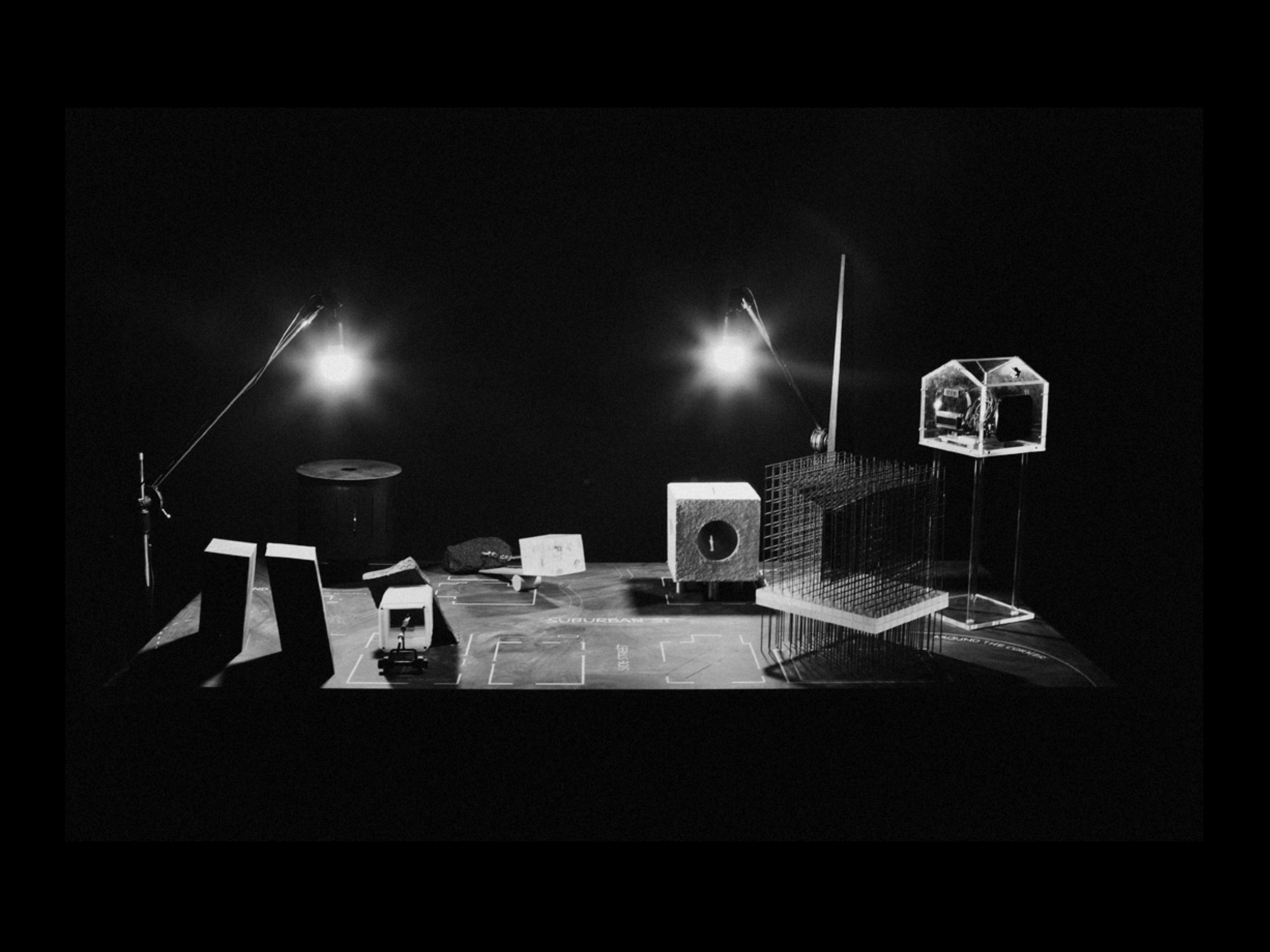

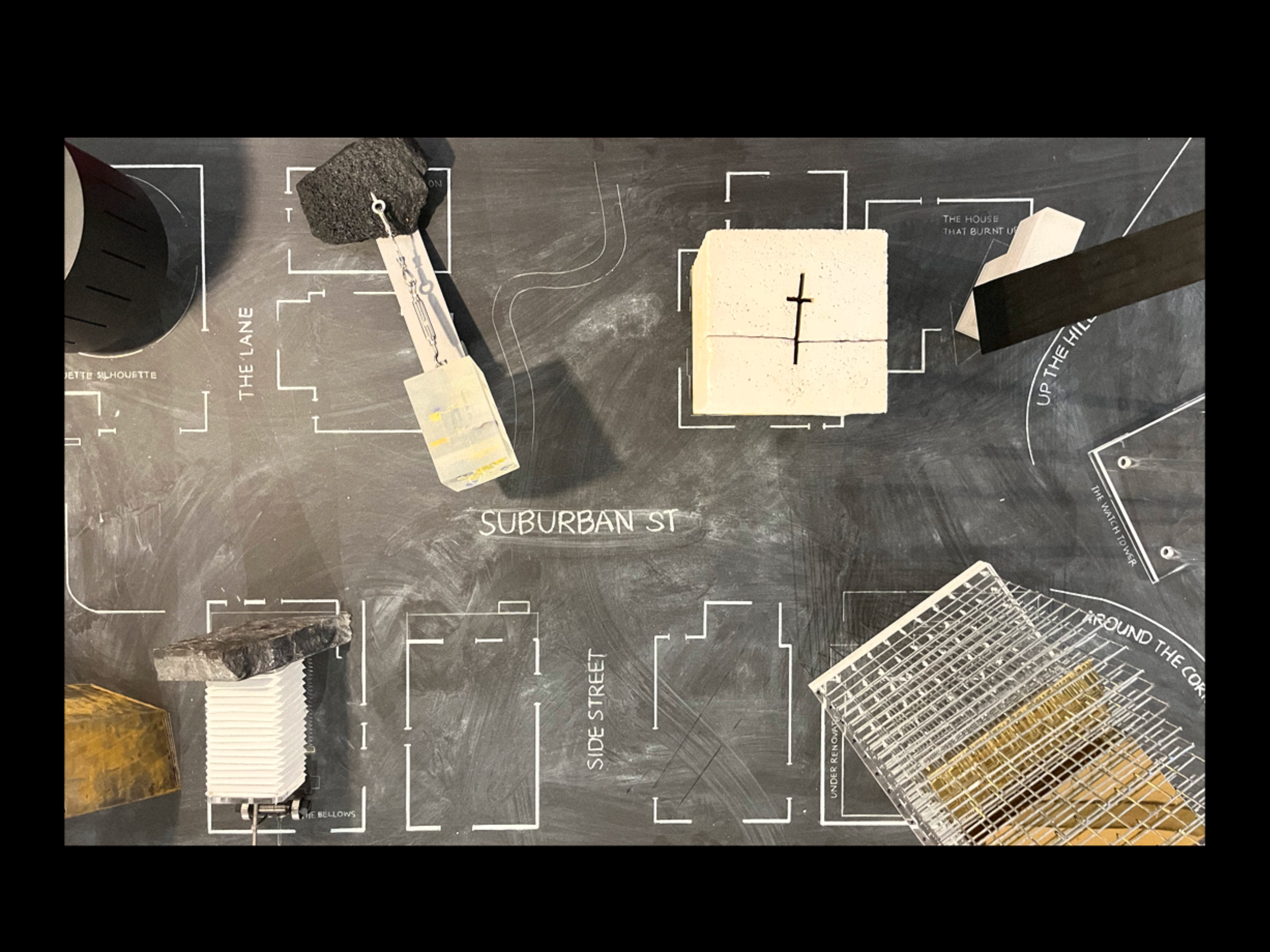

Leith’s way of grasping the severity and the life-shattering consequences of intimate violence involved the production of a series of abstract artifacts or machines that sought to embody, and in some way express, what is often inexpressible: the painfulness of persistent violence at home. Researching survivor accounts of experiencing and getting free of violence, the conceptual artifacts sought to approximate these felt consequences. Approximation is key. The artifacts are empathetic bridges; they aim to reach towards hurt, and to carry us towards this too, on the basis that its sharing calls forth awareness and, ideally, ultimately, healing. Four dark machines narrate violence: “The Watchtower”; “The Void”; “The Pirouette Silhouette”; “In the Bellows.” Rather than being isolated, the machines are depicted relationally; they are gathered together on a black tabletop called “Suburban St,” where the outlines of house plans are shown in white chalk. Reference here is to Lars von Trier’s Dogville (2003), a film similarly telling the story of family and community violence and shot within a table-like, empty sound stage.

Part 2 – Luminous Ground

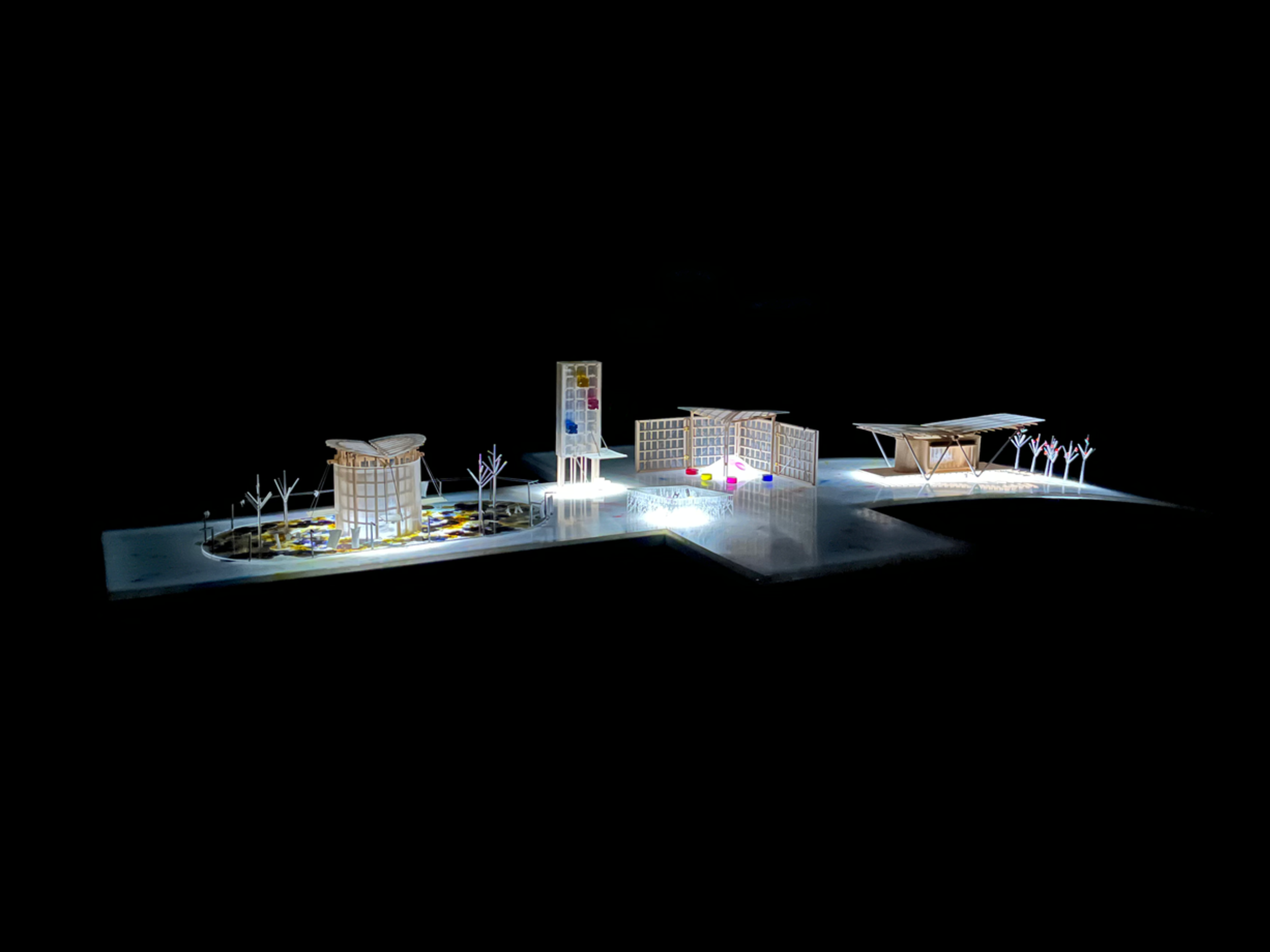

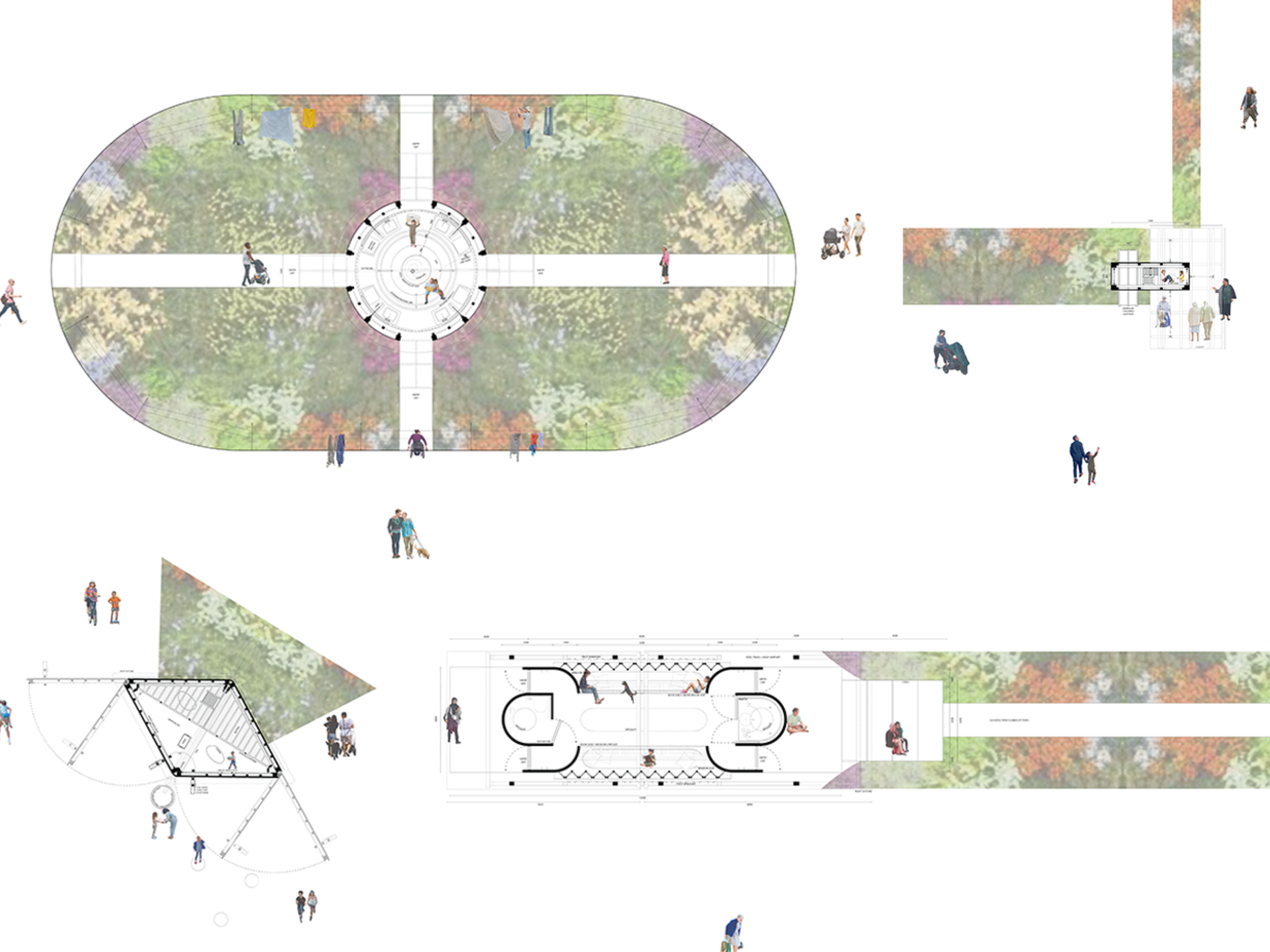

Yet if representing hurt was as far as Leith took her investigation, the project would have remained empty. More powerfully, “To the Lighthouse” entailed looking for a beyond-of-family-violence. If the earlier abstract artifacts depict “world-collapsing” circumstances—a notion Leith borrows from Elaine Scarry’s landmark text, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (1987)—a ‘reaching-beyond’ entailed finding world-building hope. Initially this focused on the craft and political agency of quilt-making, that everyday, mostly female, art that in certain circumstances has given voice to a radical societal accounting—the AIDS Memorial Quilt Project particularly. Quilts in Leith’s project embody a labour of care, the act of providing loving cover. Homes bestow these qualities too, or can, and emphasising how care could be amplified, well this might eclipse and curtail violence. So rather than turning to individual houses per se, Leith proposed that we look to streets and ways in which houses turned outward (rather than closing in the ‘nuclear’ family) might become responsive to collective care. And, of course, streets aren’t just places of vehicular transit; they have long been sites of protest and societal reckoning. Past peak oil and with the future of cars uncertain, what if all that in-between tarmac became shared spaces held in trust by neighbourhoods? And what if houses surrendered their autonomy and decantated part of their routines into shared spaces that were social, cooperative, and even joyful? This decanting found form with Leith’s lighthouses, immaculately conceived and crafted models set on a luminous street/ground. Through laborious making, much like the quilts, an embodiment of care was demonstrated. So: a ‘laundry’ and garden for drying washing; a ‘bus stop’ with street table and chairs beneath a tower for climbing and collecting games and books, all the better for waiting than getting someplace else; an outward-opening ’play room’ for the kids or the adults, that messes up and slows down the intersection; and lastly, a ‘lounge’ of sorts along with a citrus groove, for getting away, or getting together.

Home-Becoming

“To the Lighthouse” then charts a journey from worlds of loss to world-making, knowing that the latter won’t necessarily ‘fix’ the former, but that it might make loss and hurt unsustainable. The thesis knows too, that this Edenic crafting of care won’t look the same in every city neighbourhood, and that streets will ‘collectivise’ according to their own shaping of care and styles of loving. For her part, the ‘street’ Leith made is a fiction, a compilation of remembered streets she has lived in. It is not a model to be reproduced everywhere; it is a lighthouse like that of Virginia Woolf, a beacon that warns of the troubled ground we hold, but also the joy of a home-becoming invested with care. In this, the project is both sobering and astonishing.

By Andrew Douglas, supervisor