The Blood on Our Moon: A Celebration of Vessels

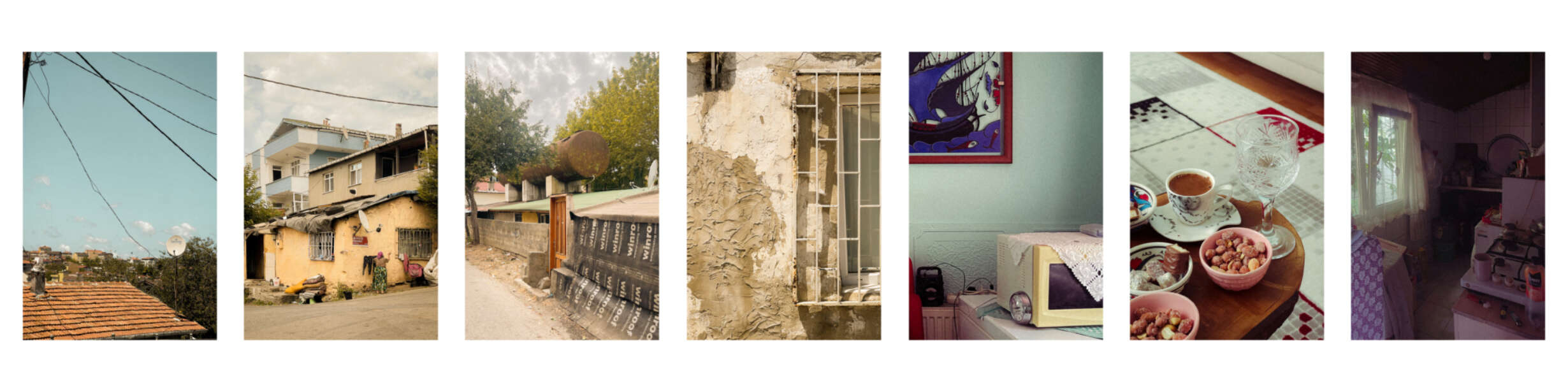

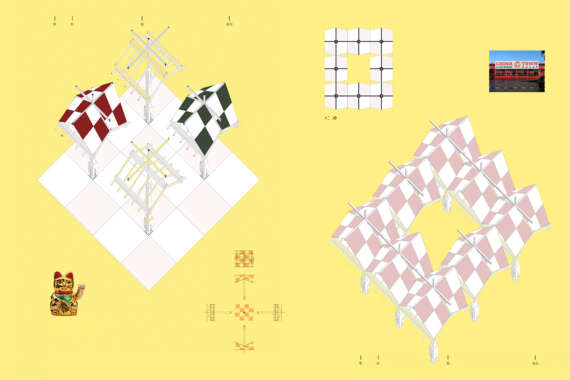

This thesis addresses the notions of home, belonging, and foreign-ness as experienced by diasporic people in Aotearoa New Zealand. As a uniquely multi-cultural society, Aotearoa’s architectural landscape fails to reflect this diversity and thus does not use the potential to celebrate as a place of a hybridisation of different cultures.

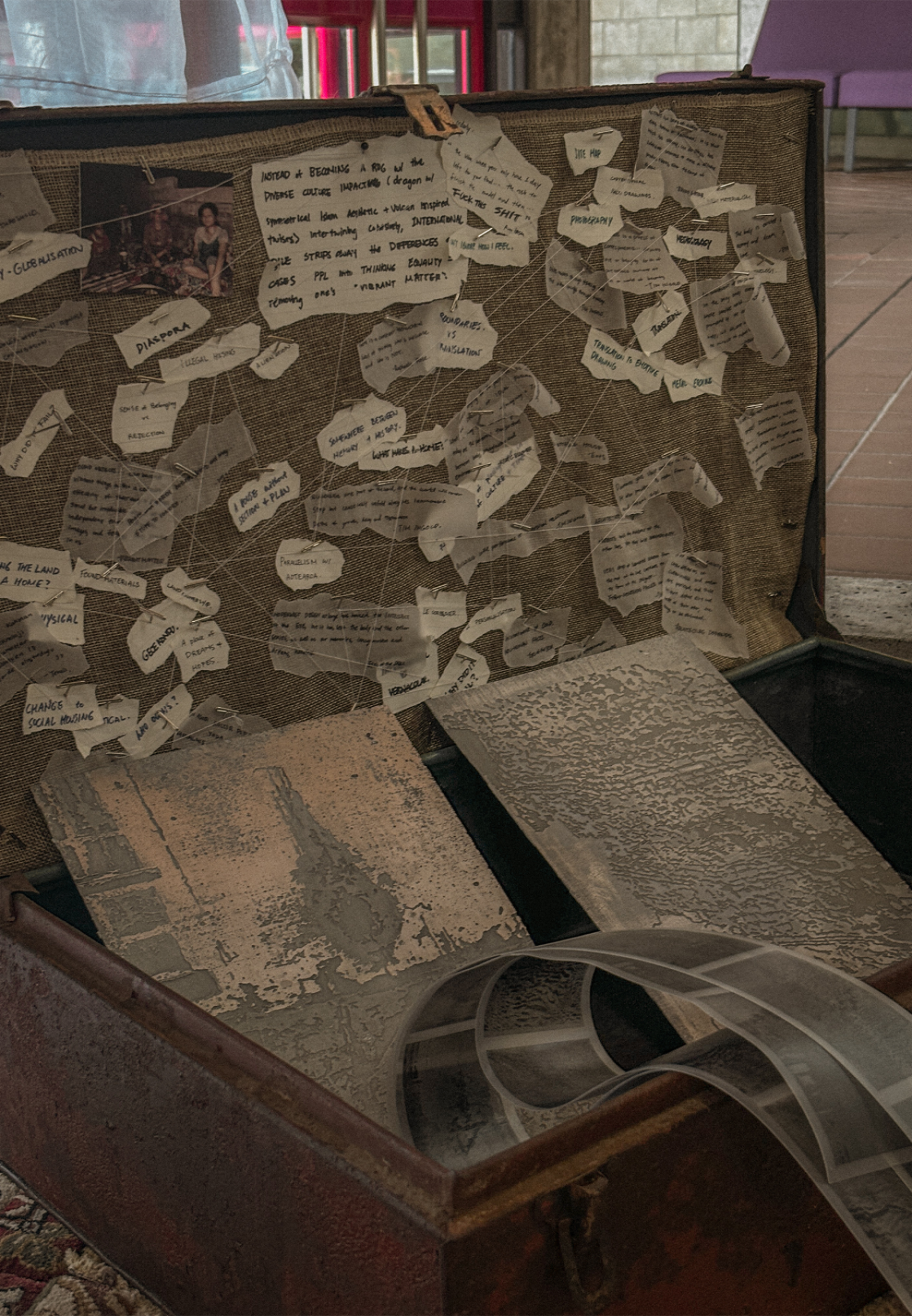

The central themes of the project are examined through the lens of the author’s lived experiences. According to William Safrad, the diasporic communities, “who have spread or been dispersed from their homeland,” long for a place to call home. A diasporic identity constantly amalgamates with different cultures and experiences that they encounter, resulting in a new coalesced identity. In zones where multiple cultures coexist, the space becomes a place of hybridisation of different cultures according to the Third Space theory by Homi K. Bhabha.

The longing as a diasporic person has prompted the fundamental question for the thesis: “How do diasporic communities architecturalise notions of home and belonging, and what lessons are to be learned for conventional architectural practises from these socio-economic-cultural spatial dynamics?”