Stock describes the knotted form and its lack of flexibility, noting the characteristic compartmentalised structure of the bungalow. While this makes the bungalow a challenge to modernise, it does provide insight into how one might restructure this compartmentalisation to better suit the contemporary domestic. There are nuances to the bungalow’s structure that are important to hold on to when re-envisioning it, such as maintaining this compartmentalisation but adjusting what this looks like and how the pieces are stitched together.

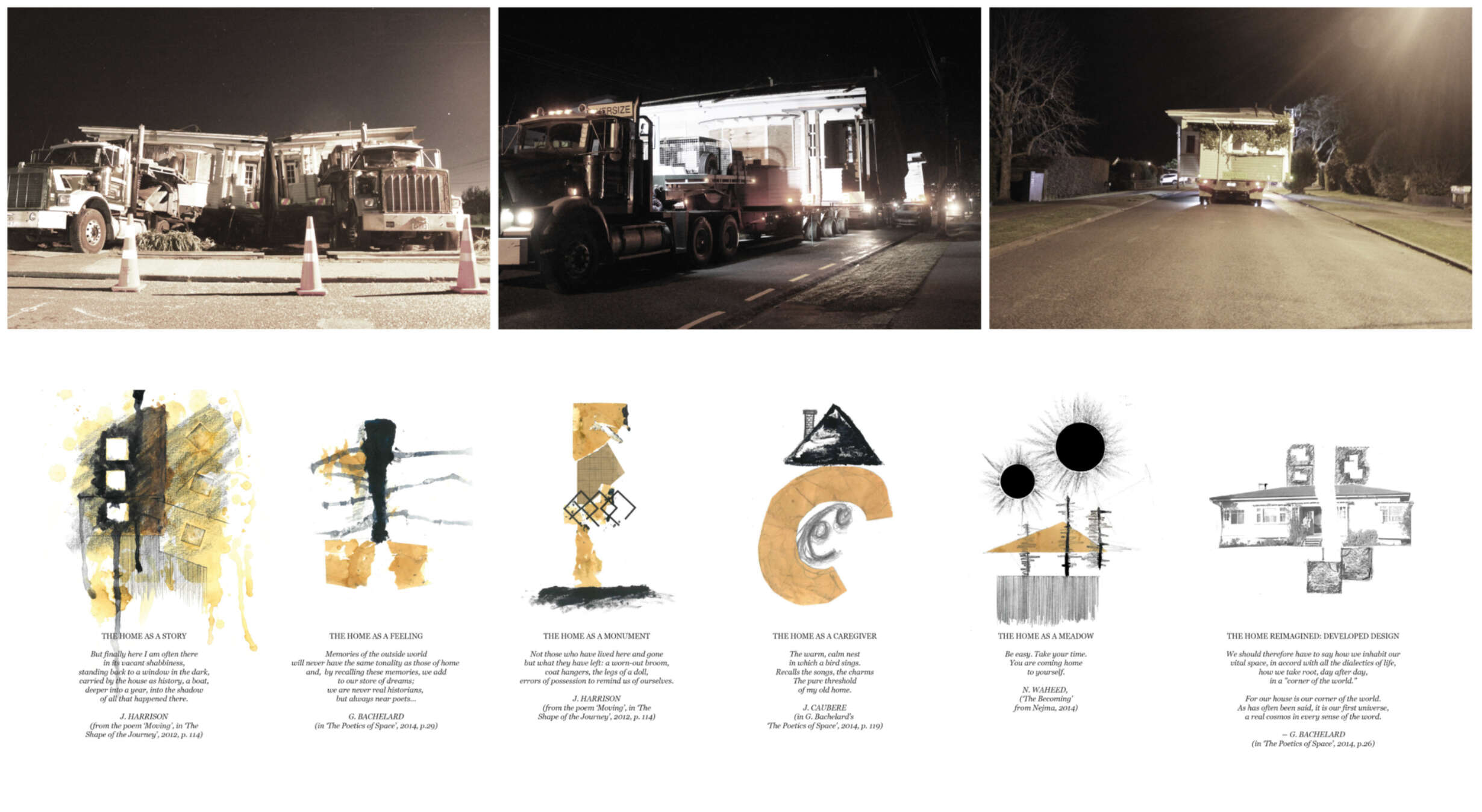

There is a quite literal stitching of the pieces of the bungalow that occurred once the dwelling was moved to the house yard and set back together, which further contributes to the poetry of stitching together pieces of domesticity – with stitching being a once common domestic duty.

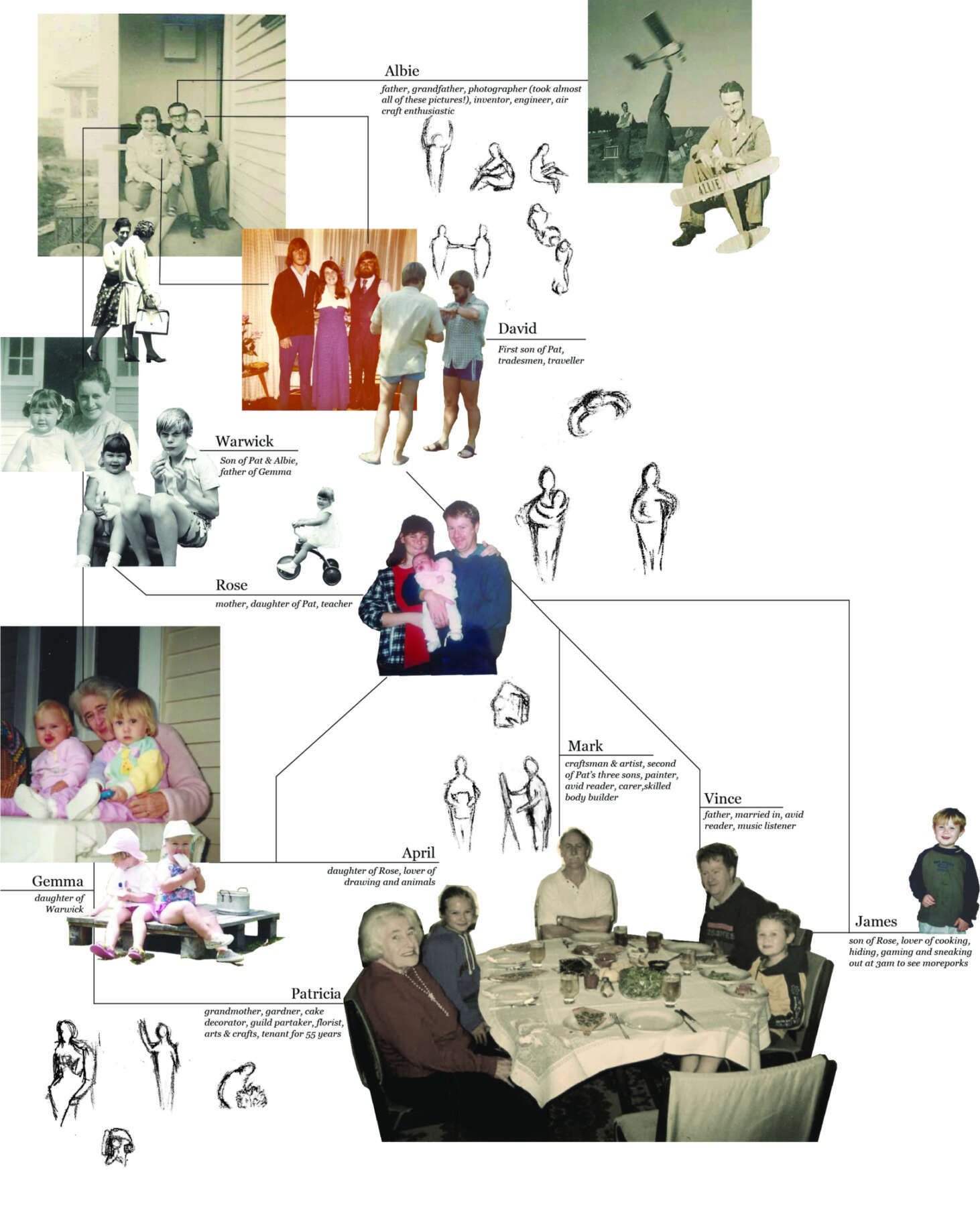

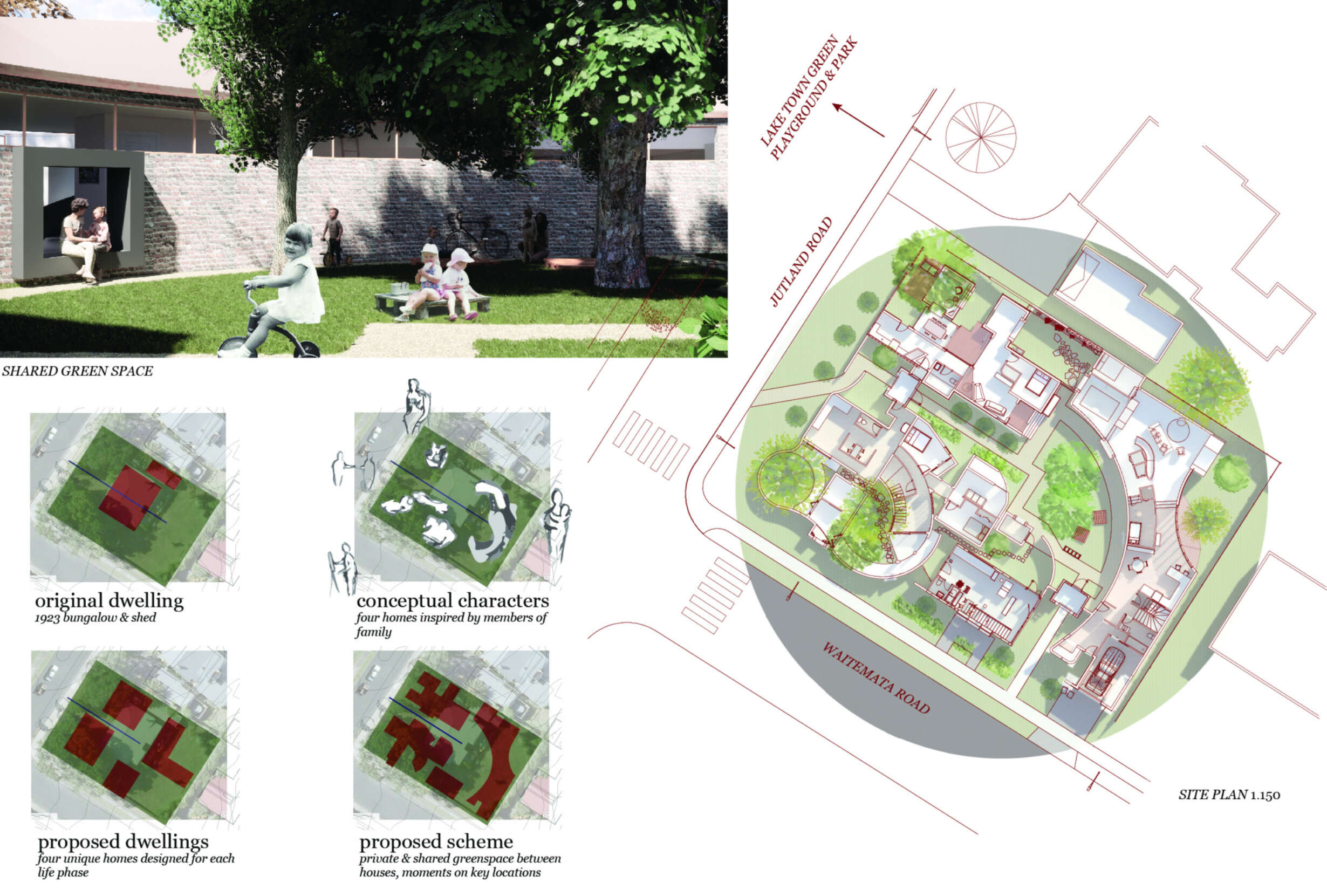

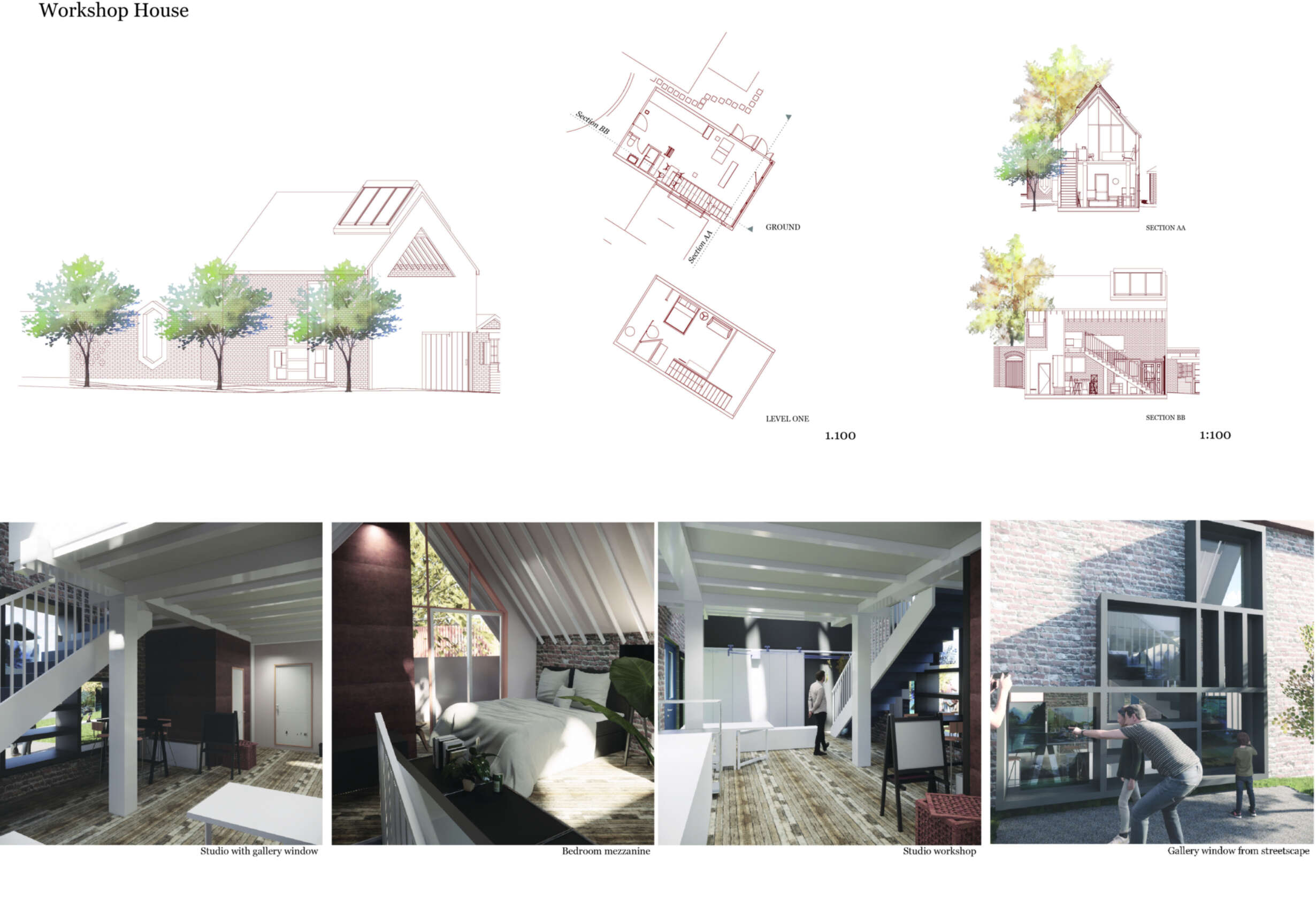

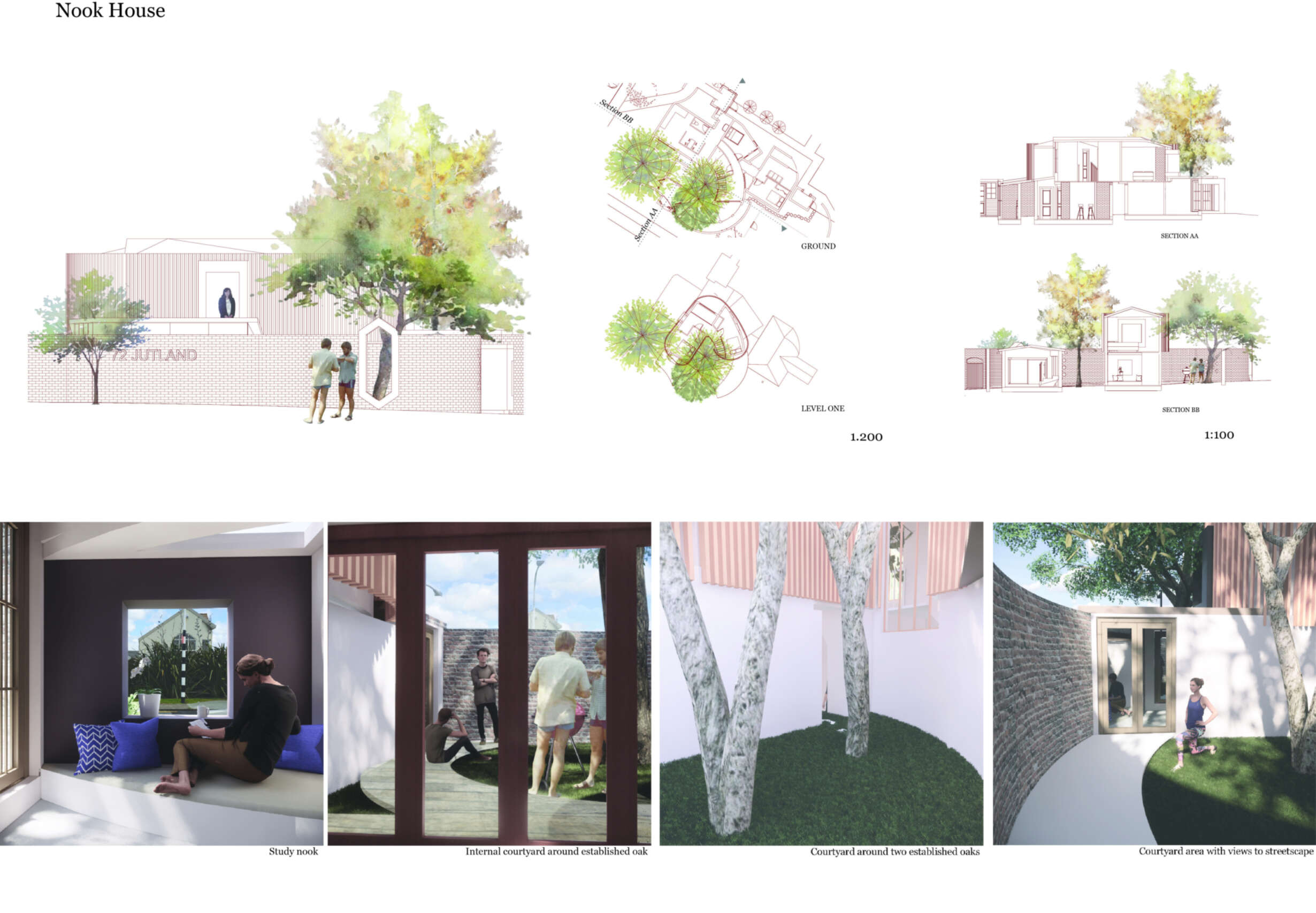

The findings of this thesis culminated in the proposal of four residences, each embodying a personality or essence from those who previously occupied the site. The areas of the home lend themselves to personal narratives of occupation, with the site a long-serving canvas for them all. The spaces we tend to favour, such as the verandah or the kitchen, become a part of our spatial landscape and our preference for such domestic spaces over the others reveals the tasks and activities we set about doing.

Specific spaces draw memories of family members, with one or two rooms perhaps more notable than others depending on what that individual spent their time doing. In this thesis, the author’s family were the individuals for whom the homes were crafted, and it is their narratives of occupation that are used to inspire their new embodied dwellings.

An attempt to hone in on the needs of the occupant, paired with stories about their use of the domestic space offered by the bungalow, inform the design. This allows a dedicated design focus for each home and minimises potential for unused, wasted space which is better used for facilitating social and community engagement.

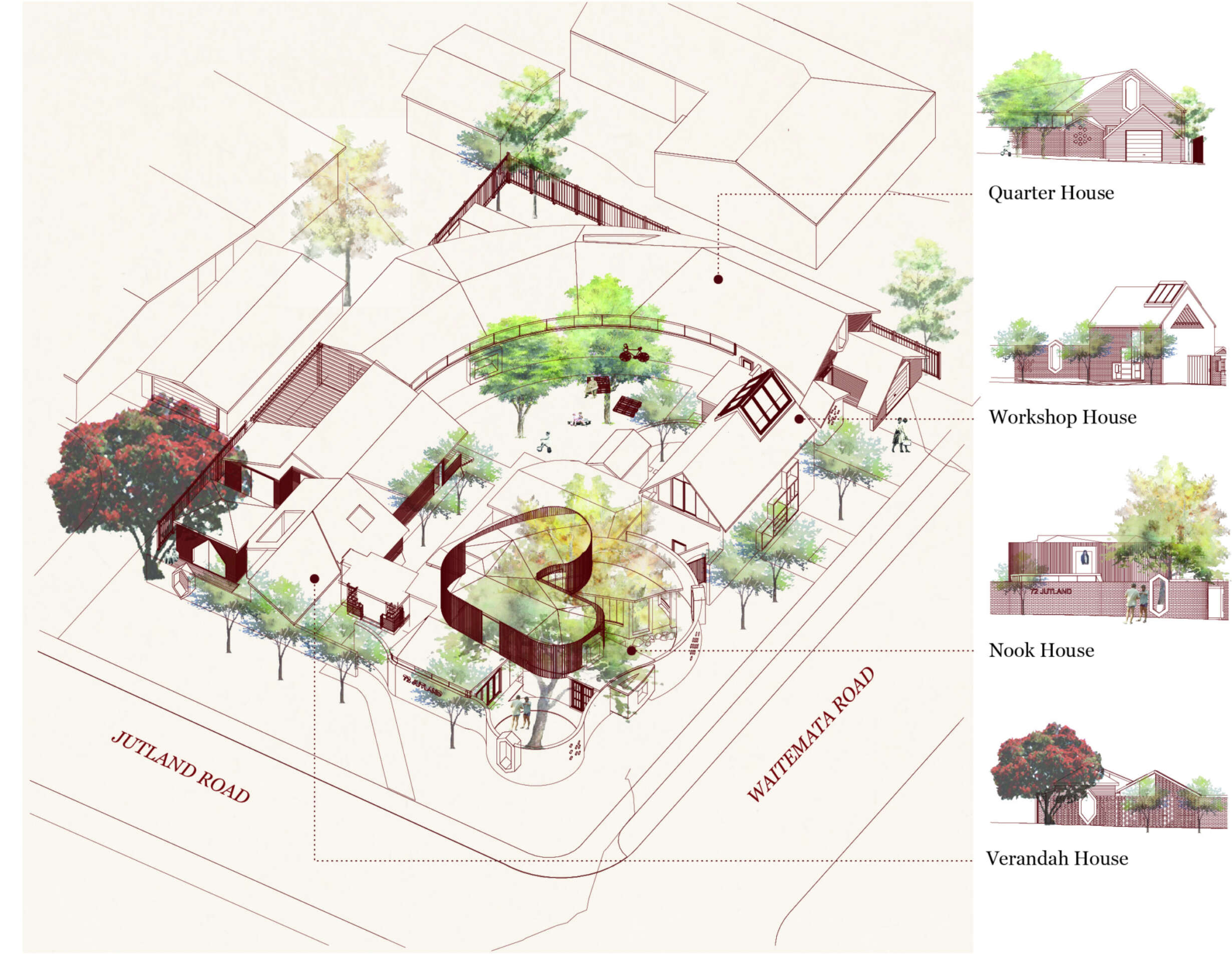

Additionally, each home takes its form from the literal shape of an interaction or personal attribute of the corresponding family member. One house appears to hug the site, while another appears to hold out a work of art. Each stand-alone residence features a wall which acts as the courtyard boundary for the neighbouring property. This is an observed natural boundary as opposed to a marked, guarded one; there is no ambiguity about each space in order to clearly communicate where the limits of occupation exist.

The courtyards weave throughout the site, permitting the established trees, some of which date back to the site’s conception, to continue growing. This aids in maintaining the street scape and assists in creating a connection to the past through nature.

At the centre of the four homes is a shared internal courtyard, through which a path winds. The path follows that of the cut made through the walls of the original dwelling before it was separated and moved off-site. In this story, the void is now reinstated as a path that leads to the meeting of four walls – each of a separate home – and pulls them together in a place of connection.

The forms of each home engage their own personality dependent on their dedicated occupant. Home can be different things to different people; consistent interpretations are used throughout all residences, such as a preference for green space (biophilia), site narrative and safety. However, the activities within the home differ depending on life phase.